Production licence awarded

They were Statoil, with a 50 per cent interest, BP Norway Limited UA with 20 per cent and A/S Norske Shell with 30 per cent. Shell was appointed operator.

This award was made in Norway’s eighth offshore licensing round, when 14 such production licences were issued covering a total of 16 blocks to various companies and constellations.

These holdings were spread for the first time across the whole Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), from the North Sea in the south the Norwegian Sea, and the Barents Sea in the far north. To the surprise of many, given the “Norwegianisation” policy of the day, foreign companies did well in terms of operatorships. Six of the 14 were secured by international players.

Licence and the award process

The process of awarding a production licence usually begins with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) inviting the oil companies to bid for NCS blocks.

Acreage on offer is determined by the MPE, with the companies putting in bids for the blocks they regard as most attractive – either singly or in partnership with others.

They assess blocks by the probability of making a discovery and how a licence would fit with their strategy. A company could, for example, apply in areas where they already have production.

Rettighetshavere på Draugen, illustrasjon, plakat,

Rettighetshavere på Draugen, illustrasjon, plakat,The MPE decides who gets a licence, and the share each partner will have in it. Costs and revenues are usually divided between the licensees on the basis of their relative equity interest. All fields on the NCS have several partners, with their different roles in the licence determined by the MPE. One is appointed operator.

The latter has the job of organising exploration for petroleum as well as developing and operating a possible discovery – subject to the support and supervision of the other partners.

An operator is usually the most experienced player in a licence. It must also have the resources, expertise and personnel needed to conduct all relevant operations and activities in line with the applicable regulations.

The operator is therefore the partner in a licence with day-to-day responsibility for its activities. As mentioned above, Shell has fulfilled this role on Draugen.

But the other licensees are not freeloaders. Although the operator handles everyday work, its partners are meant to contribute actively in ensuring it complies with the rules.

Norway’s offshore regulations require them to support and challenge the operator, serve as a competent partners and see to it that activities are pursued in a prudent manner.

Holdings in a licence can change over time through purchase and sale (farm in/out) of interests as well as regulatory changes. In Draugen’s case, a political settlement played a key role in the first adjustment of percentage shares in the field.

Oil compromise

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,A broad compromise on oil policy emerged in parallel with the eighth licensing round. This involved the non-socialist coalition between the Conservatives, Christian Democrats and Centre Party under premier Kåre Willoch, and the opposition Labour Party.

It settled a political controversy over the place of state oil company Statoil in Norway’s petroleum sector. Many people, particularly in the Conservative Party, felt it had become over-mighty. They also viewed its cash flow as excessive in relation to the country’s gross domestic product.

The solution was to break up Statoil’s holdings, with a portion of them being transferred to a new legal entity called the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI).

Established with effect from 1 January 1985, this had no direct responsibility for operations. Statoil was to manage the SDFI and handle its operational and commercial functions.

The compromise aimed to create a model which would provide continuity for state participation in the Norwegian petroleum sector regardless of changing political conditions. Statoil’s interests in Draugen were among those split. The state still held 50 per cent, but that was now divided between 30 per cent for the SDFI and 20 per cent for the company.

This change had little significance for the Draugen project during the early years. The government, through the SDFI, still had to meet part of the development costs earlier paid by Statoil. The direct consequence for Draugen operations was first felt in 2002, when another state-owned company took over management of the SDFI’s interest – which had risen to 47.88 per cent by then.

Made necessary by the partial privatisation of Statoil in 2001, this moved transferred responsibility for the SDFI to the newly formed Petoro AS. The latter was given a commercial mandate, but with certain restrictions on its operations. It could not, for example, act as an operator for fields on the NCS.

Sliding scale

The first change in licence interests on Draugen came in 1988, when the state’s share in the field – split between Statoil and the SDFI – rose from 50 to 65 per cent. Shell and BP had their holdings reduced to 21 and 14 per cent respectively.

This revision utilised a provision introduced with the third licensing round in 1974, which entitled the government to raise the state’s share in a licence.

Exercisable once a plan for development and operation (PDO) had been approved, this “sliding scale” principle applied to all licences awarded on the NCS from the third round.

Up to the eighth round, when the Draugen licence was awarded, the sliding scale provided that Statoil’s interest should depend on the size of plateau output from a possible field.

Any increase in this level of production would mean that the state company’s share could be increased in accordance with the scale. When a licence was awarded, before exploration drilling began, great uncertainty prevailed about the size of oil and gas reserves a reservoir might contain and how far they could be recovered. These rules changed after the eighth round and the creation of the SDFI. With effect from the ninth round, the sliding scale was replaced by a government option independent of production.

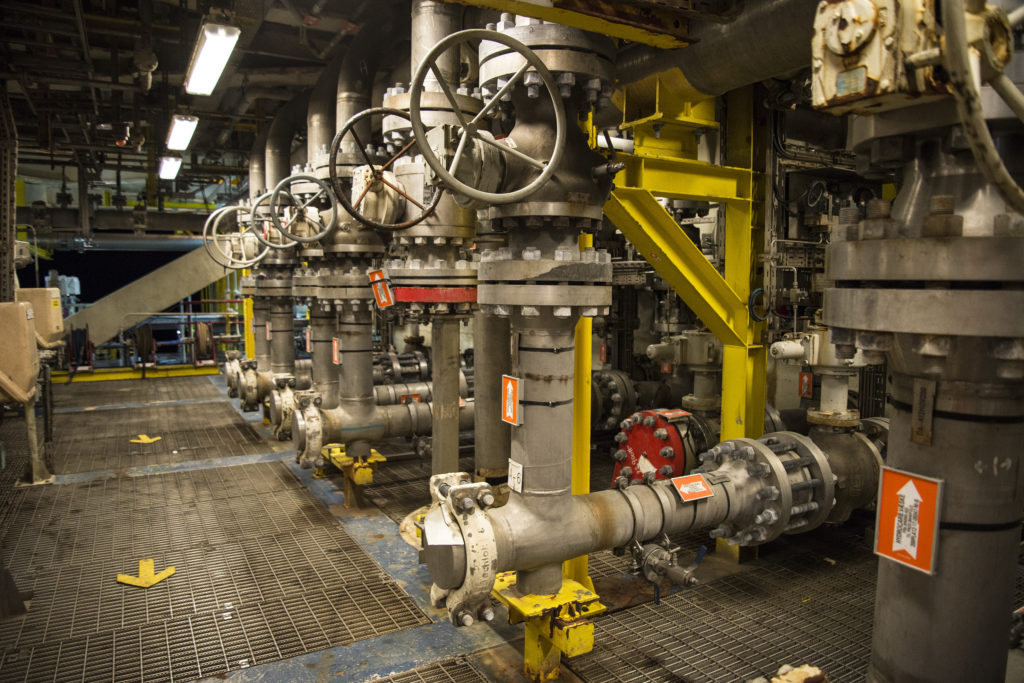

Dekket design og innhold, engelsk, forsidebilde, hovedprosessen, rettighetshavere på draugen,

Dekket design og innhold, engelsk, forsidebilde, hovedprosessen, rettighetshavere på draugen,The PDO for Draugen was debated by the Storting (parliament) in the autumn of 1988, after it had been considered by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE).

According to a recommendation from the ministry, the plateau production of 90 000 barrels of oil per day (b/d) proposed by operator Shell should be increased to 110 000.

This rise would have lifted the field to a new level on the sliding scale, where the increase in the state’s collective holding (Statoil plus SDFI) would go up from 65 to 75 per cent. That would have had a big negative impact on the private-sector companies in the licence. Shell and BP reacted sharply, and launched an effective lobbying campaign aimed at the Storting’s standing committee on energy and industry.

The latter was chaired by Ole Gabriel Ueland from the Centre Party, which took a sceptical view in general to increasing production from the NCS. Rejecting the MPE’s proposal, the committee recommended instead that the plateau rate for oil output should remain at the 90 000 b/d set by Shell. But it also approved an increase in the state’s share of Draugen to 65 per cent, with 19.6 per cent allocated to Statoil and 45.4 per cent to the SDFI. As noted above, Shell and BP were reduced to 21 and 14 per cent respectively.

The Storting accepted the committee’s recommendation. It voted to increase the state share in line with the approved production profile to 65 per cent at the expense of the foreign licensees. Statoil was therefore not affected.

In its budget recommendation no 8 (1990-1991) to the Storting, the standing committee on oil and industry proposed abolishing the different treatment of Norwegian and foreign licensees.

The sliding scale was later exercised again on Draugen. In recommendation no 197 (1994-1995) to the Storting, its energy and environment committee approved a new MPE proposal to increase the state’s holding from 65 to 73 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Energy and environment committee. (1995). Innstilling fra energi- og miljøkomiteen om utbygging og drift av Njordfunnet, fastsettelse av statlig eierandel for feltene Draugen og Brage samt orientering om Norsok-arbeidet. (Proposition no 54 to the Storting). Recommendation 197 (1994–1995) to the Storting. Downloaded from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1994-95&paid=6&wid=aIb&psid=DIVL622.

Norwegian membership of the European Economic Area now meant that discriminating between foreign and Norwegian companies was no longer possible.

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,When the sliding scale was exercised in 1995, the SDFI therefore had to compensate the other licensees for past spending based on their percentage shares. The licensees agreed to this. The committee now accepted the government’s proposed increase in the state’s interest. For the sliding scale to take effect, however, plateau production had to rise again to 150 000 b/d.

That was unacceptable to the Centre Party, which accordingly demanded the insertion of a dissenting comment in the committee’s recommendation. According to the party’s members, an overall assessment – including considerations of long-term resource management and the decision to stabilise carbon dioxide emissions – meant that the Storting should reject government plans to raise output.

Members of the Socialist Left party also refused to support the proposal, but this secured the backing of a majority on the committee and later in the Storting.

Farming in/out

The government is not the only player who can contribute to changes in licence interests. Holdings in attractive licences can be bought or sold like shares in normal companies. Known as farming in or out of the licence, such transactions may reflect a desire by companies to streamline their operations and to concentrate on certain geographical areas.

These changes in interests are important for improving recovery, since new licensees may see opportunities to extend the producing life of existing fields and reduce their costs. Holdings in licences can be swapped as well as traded, and changes in interests may also occur because licensees pull out, are taken over or merge with others.

Oil companies differ over the potential and profitability of oil and gas fields, and the original licensees may sell their interests to others with a more optimistic view.

The latter may take a different view of the reservoir, cost trends or the application of new technology which they believe will help maintain profitable production.

All farm ins/outs and interest swaps must be approved by the government.

No exception

A new company accordingly joined the existing licensees on Draugen in 1998, when Norsk Chevron acquired a 7.57 per cent holding from the government.

In addition to the Chevron stake, Statoil/the SDFI had 57.88 per cent at 31 December that year, Shell was down slightly to 16.2 per cent and BP held 18.36 per cent.

Three years later, Chevron and Texaco merged to form ChevronTexaco. The company’s name was changed back to Chevron in 2005, with Texaco as one of its brands.

Global impact

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,

Rettighetshavere på Draugen,An event elsewhere had consequences for the division of interests on Draugen. This began on 20 April 2010 with a gas blowout and subsequent explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig. Located on the Macondo field in the Gulf of Mexico, this event developed into a fire and caused the deaths of 11 people. Another 15-20 were injured. Oil flowed freely to the sea for 87 days, causing extensive environmental damage until the leak was stopped.

BP was operator on Macondo, and had to pay tens of billions of dollars in compensation after the disaster. To meet this bill, it was forced to sell off assets.

Norske Shell entered into an agreement in 2012 to acquire BP’s 18.36 per cent holding in Draugen, raising its share to 44.56 per cent. That left the division of interests at 31 December 2012, in addition to Shell, at Chevron with 7.56 per cent and Petoro – which secured the Statoil and SDFI holdings in 2002 – with 47.88.

Two years later, it was Chevron’s turn to pull out. Its stake in the Draugen licence was taken over by German-owned VNG Norge as part of a long-term commitment to NCS.

This company had made a conscious decision to strengthen its position on the Halten Bank. It already had interests in Njord and Hyme, and is operator for Pil og Bue (later named Fenja) – the biggest oil discovery on the NCS in 2014.

Shell out?

Royal Dutch Shell launched a USD 70 billion bid for all the shares in BG Group in 2015, seeking to expand at a time when low oil prices were put pressure on the petroleum profitability.

The previous wave of mergers in the international petroleum sector had been in the late 1990s, following the Asian economic crisis, with oil giant ExxonMobil as one of the outcomes. Shell had stood on the sidelines then, despite rumours that it might take over BP. Such acquisitions cost money, and Royal Dutch Shell now found that it needed capital.

Its interest in Draugen went on sale in March 2018, and who will be the buyer and take over as operator remained unclear at the time of writing. Shell’s stake in Gjøa was also put on the market in a sell-off which actually started in 2017 with holdings in several British fields.

During the autumn, the company sold a 9.92 per cent interest in Norway’s Polarled gas pipeline and three per cent of its 15.03 per cent stake in the Nyhamna gas plant.

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, engelsk

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, engelskIn the latter case, however, Shell will remain responsible for running the facility in its role as technical service provider to operator Gassco. The Ormen Lange gas field in the Norwegian Sea is not part of these sales. Its operations organisation shares premises with the Draugen team at Råket in Kristiansund. It remains unclear whether and how this collaboration will continue in the future, but Norske Shell has promised to remain in Kristiansund for the time being.

Stavanger’s leaning towerFast find