Offshore safety in Norway to 1990

This was anti-union and imposed strict discipline on the rank-and-file. The workforce was also almost entirely male, and a “cowboy” culture developed where people were ready to take chances.

A number of accidents occurred. With the priority given to efficiency and productivity, safety measures were regarded to some extent as unnecessary costs. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Smith-Solbakken, Marie (1997). Oljearbeiderkulturen: historien om cowboyer og rebeller, Trondheim: 72.

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, engelsk,

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, engelsk,Operations off Norway were dominated by young personnel, with a big foreign component. The climate was fairly rigorous, and the land was further away than in earlier offshore activities.

The number of serious accidents eventually built up, and efforts to improve safety became more systematic.

So how did thinking about safe working develop in the confrontation between the cowboy culture and Norwegian traditions and a stricter regime? And how did planning of Draugen build on earlier experience?

Working Environment Act

One step towards improving conditions offshore was to extend the Working Environment Act adopted by Norway in 1977 to the NCS. Applying this legislation to the oil sector was under discussion even before it came into force.

The large number of foreign companies and employees involved, often on short-term contracts, posed particular difficulties in establishing a uniform system and ensuring adequate control.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, annual report 1977: 6.

A push towards introducing the Act offshore was provided by a fire which affected the Ekofisk Alpha platform in the North Sea on 1 November 1975.

Immediately after this incident, the industry ministry required operator Phillips Petroleum to establish a safety delegate service for the field.

Furthermore, a safety and environmental committee was established. This became the forerunner of the working environment committee later required under the Act. [REMOVE]Fotnote: https://snl.no/Alfa-plattform-ulykken

Temporary regulations based on the legislation, with some exceptions, were applied to fixed installations on the NCS with effect from 1 July 1977.

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) was appointed as the regulatory authority.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, annual report 1977: 50. The Act was not extended to floating facilities until 1992.

A “tripartite” collaboration between employers, employees and government formed the cornerstone of Norway’s working environment regime. The workers had a legal right to be consulted.

Such employee participation was not normal in the American labour relations practice followed by a number of the international oil companies.

The Act therefore aroused great opposition, and the meeting between US and Norwegian work cultures proved difficult at times. Some fears were expressed in the oil industry that it would boost costs and cause delays for development projects.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 4 April 1978, “Arbeidsmiljøloven fryktes i Nordsjøen. Uviss innvirkning på den videre Statfjord-utbyggingen”.

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990,

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990,A main goal of the legislation was that working environment problems should be resolved as far as possible at local level through joint action by employees and employers.

One of its key provisions was that technology should be tailored to people, and requirements were specified for designing a workplace.

That involved stipulations for such physical aspects as lighting, ventilation, noise pollution and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Employee codetermination would be ensured with mandatory safety delegates elected by them and the working environment committee drawn from both management and rank-and-file.

Company leaderships were obliged to collaborate with the delegates, who could halt a work operation on their own judgement if they considered it likely to cause an accident.

At the same time, each employee was to help create a good and healthy working environment and seek to prevent accidents and damaged to health. They had a legal duty to use prescribed PPE.

However, the main responsibility for safety was placed unambiguously on the employer.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge (2007): “Sikker atferd i et historisk perspektiv”, in Tinmannsvik (ed): Robust arbeidspraksis. Hvorfor skjer det ikke flere ulykker på sokkelen?, Trondheim.

The government supervised compliance, and could impose orders on the operators if they failed to follow up working conditions.

Bravo blowout and offshore safety

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, engelsk,

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, engelsk,After the uncontrolled blowout on the Ekofisk 2/4 B (Bravo) platform in April 1977, it became clear that Norwegian offshore safety was not good enough and the risk level stood too high.

The government launched an extensive offshore safety research programme in 1978. Although this concentrated on the safety of people, it also identified risk factors related to the environment and material assets.

Attention was given to safety management, defined as conscious measures to increase the probability of avoiding harm and harmful incidents. Preventing fire and explosion occupied a key place.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kårstad and Wulff (1983). Sikkerhet på sokkelen, Oslo: 94.

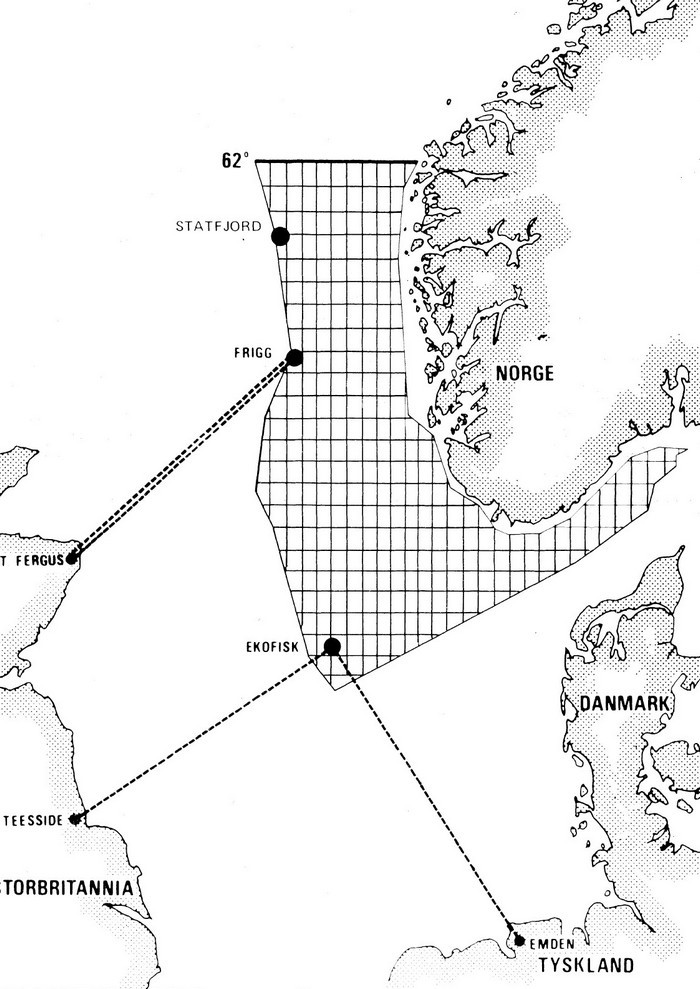

kart, Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990

kart, Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990The internal control principle was developed by the NPD in the wake of the Bravo blowout and the extension of the Working Environment Act.

Targeted at the oil companies, this concept replaced direct inspection by the regulators with a duty on operators to conduct safety checks and follow up work on safety.

The commission of inquiry into the Bravo incident concluded that it was caused by human error, which had its roots in turn in weak administrative systems, instructions and routines.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, Johannes (1999). På tidens skanser, Trondheim: 184.

A number of studies into blowout risk and impact assessments of such incidents were carried out.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Official Reports (NOU)1979:8. Risko for utblåsning på norsk kontinentalsokkel.The oil they released could potentially harm the natural environment, including fisheries.

Kielland disaster and internal control

The capsizing of the Alexander L Kielland accommodation rig (flotel) in 1980 has been very significant for safety thinking in the Norwegian petroleum sector.

With 123 lives lost, it ranks as Norway’s worst-ever industrial disaster. The subsequent inquiry highlighted inadequate safety training and exercises, and lack of life-saving equipment.

One of the big changes in the wake of the accident was that internal control became systematised. This recognised that rapid technological advances made it difficult for the government to keep its regulations relevant and up-to-date.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Official Reports (NOU) 1987:10. Internkontroll i en samlet strategi for arbeidsmiljø og sikkerhet: 39.

The outcome was the publication in 1981 of official guidelines for internal control by licensees in the petroleum sector.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.ptil.no/hms-styring-og-ledelse/tilsynsordningen-fra-detaljstyring-til-malstyring-article6681-824.html. A duty to operate prudently in accordance with the regulatory requirements was imposed on the responsible companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge (2007): “Sikker atferd i et historisk perspektiv”, in Tinmannsvik (ed): Robust arbeidspraksis. Hvorfor skjer det ikke flere ulykker på sokkelen?, Trondheim.

Piper Alpha and planning on Draugen

Another major accident, this time on the UK continental shelf, had direct consequences for safety thinking related to Draugen.

The Piper Alpha platform caught fire and exploded in 1988, causing the deaths of 167 people – two-thirds of those who had been on board.

Its direct cause was the removal of a pump for overhaul. A misunderstanding meant an attempt was nevertheless made to start it. That led in turn to a gas leak with subsequent ignition, fire and explosion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.norskoljeoggass.no/no/Hydrokarbonlekkasjer/Hvorfor-er-det-viktig-a-unnga-HC-lekkasjer/Piper-Alpha/.

A notification had been given to the control room on a work permit that the pump must not be started, but this had failed to reach the right people.

Piper Alpha was originally designed in 1976 for oil production, and its firewalls were constructed to protect against the heat from an oil blaze.

However, they could not withstand the pressure created by a gas explosion. A gas module was installed in 1980, with gas compression immediately beneath the control room.

The disaster focused extra attention on the need to tighten up requirements for safety procedures related not only to oil and gas operations but also to platform design.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.ptil.no/artikler-i-sikkerhet-status-og-signaler-2012-2013/piper-alpha-marerittet-article9136-1094.html.

A more complex causal picture was revealed by the official commission of inquiry, with a number of faults and deficiencies in equipment and reporting routines as well as poor communication.

Lack of control and coordination was a key finding, with poor follow-up and checking of work permits in the years ahead of the accident.

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, rapport, faksimile

Sikkerhet offshore fram til 1990, rapport, faksimileThe report contained a large number of recommendations, including a requirement for all operators to prepare a safety case.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.oceanstaroec.com/fame/2005/hse.htm

This is a structured document which establishes the safety challenges faced and identifies the responsibilities of the operator company’s management.

Shell UK paid close attention to the Piper Alpha inquiry, and the Draugen development organisation secured access to updated information which could be used in the project.

An extensive safety case was developed for the field, which built in part on the Piper Alpha recommendations as well as practice in Shell’s international organisation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Mahdi Hasan, 11 August 2017.

A number of companies developed a health, safety and environmental (HSE) case, which listed challenges in these areas and clarified the measures taken and the procedures in force.

These cases analysed which parts of the process could lead to pollution as well as the probability of an accident occurring,[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Environmental Risk Assessment of a Leakage based Injection Water Discharge from Draugen on the Norwegian Continental Shelf”, SPE/EPA/DOE Exploration and Production Environmental Conference, 2001.

while listing job categories and the associated responsibility.

An HSE case was also drawn up for Draugen using a structure developed by Shell International. This formed part of a strategy for global standardisation, where the same governing documents, guidelines and controls would apply everywyhere.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hoem, Anders (2014), How does the Shell global HSSE control framework align with the Norwegian HSE regulations in light of general principles of risk, risk management, asset integrity and process safety? Master’s thesis in risk management, University of Stavanger.

The Shell safety case has been used in a number of countries.

In addition to identifying the risk of major and minor accidents, the Draugen HSE case covers working environment factors such as ergonomics, the psychosocial environment and exposure to chemicals and noise.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Glas and Kjær (1996), “Draugen HSE Case – Occupational Health Risk Management”. International Conference on Health, Safety and the Environment. It is updated every five years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Draugen HSE Case, dated 30 April 2012: 15.

Read more in the article on Draugen and safety.

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, kart, illustrasjon, engelsk,

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, kart, illustrasjon, engelsk, hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, engelsk

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, engelsk hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, nyhet, engelsk,

hvem har ansvaret når alarmen går, nyhet, engelsk,