Kristiansund’s earlier history

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,Two decades of efforts by local politicians to become part of Norway’s oil adventure preceded the arrival of the Shell team at Råket. This work began as early as 1970.

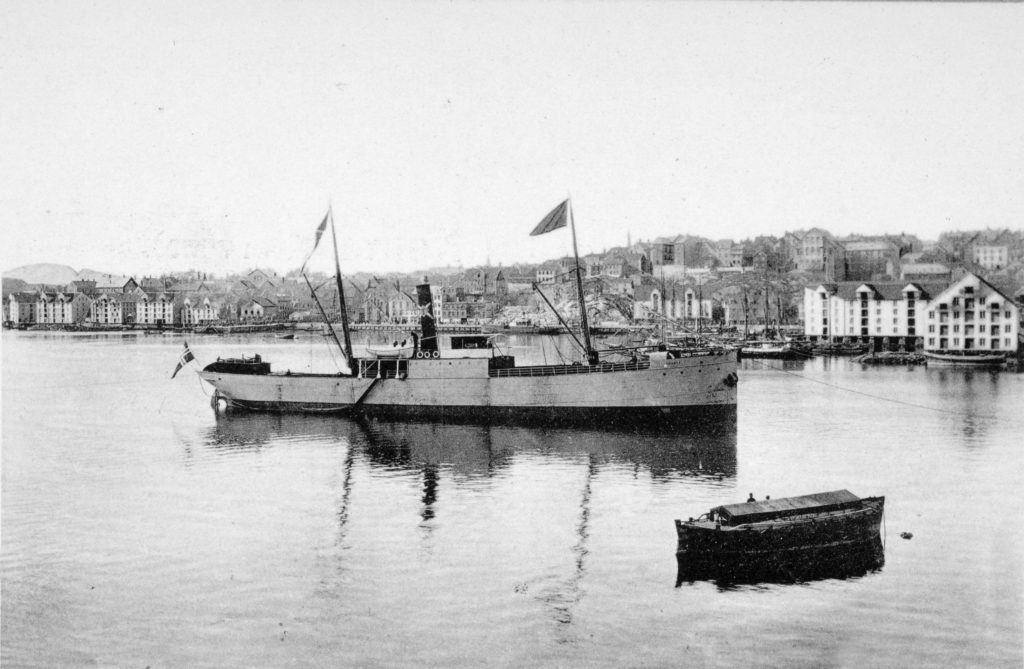

The sea and the harbour have always been the basis for Kristiansund’s existence. While the former yielded raw materials such as fish and oil, the latter lies in the middle of the Leads, the sheltered shipping channel along the Norwegian coast.

Protected from and accessible in every kind of changeable west-coast weather, the port – which could be clogged with fishing vessels at times – has always been the centre of the town’s life.

Along with the routes eastwards through the fjords to the communities in Nordmøre, this combination of resources and a good natural harbour explain why Kristiansund lies where it does.

It grew on the basis of timber exports, fishing and the production of dried and salted cod (klippfisk). Today, its commercial life is centred on Halten Bank offshore operations.

Kristiansund has two hinterlands – the fishing areas to the west, with Kvernes, Grip, Edøy and Aure, and the fjord districts such as Tingvoll, Surnadal, Sunndal and Stangvik.

Agriculture was the mainstay of these inland communities, while sawmilling and fishing in the fjords provided good extra revenues.

The town did not acquire its present name until 1742, when it acquired “commercial rights” (kjøpsrettigheter). Originally known as Lille-Fosen or Fosna, it was then dubbed Christianssund after King Christian VI of Denmark-Norway. The change to Kristiansund followed later spelling reforms in Norway.

Periods of boom and bust have characterised the port’s economy, and its industry has had a one-sided focus on producing goods for a world market. Local development has therefore been governed by international trends.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Lille-Fosen was still a tiny settlement with only five or six taxpayers. Trade was dominated by the fishing villages of Kvernes and Grip.

A dramatic international slump in fish prices which hit dried fish in particular changed this. People moved inland from the fishing centres and timber emerged as a new source of trade.

The Dutch era

Holland was the leading shipbuilder in Europe during the 16th century, with a big demand for timber. It had little forest of its own, but could buy large quantities cheaply in Norway.

This led to an extensive trade between the Dutch province and Norwegian “loading places” (ladesteder) along the whole coast from the Swedish border and right up to Nordmøre.

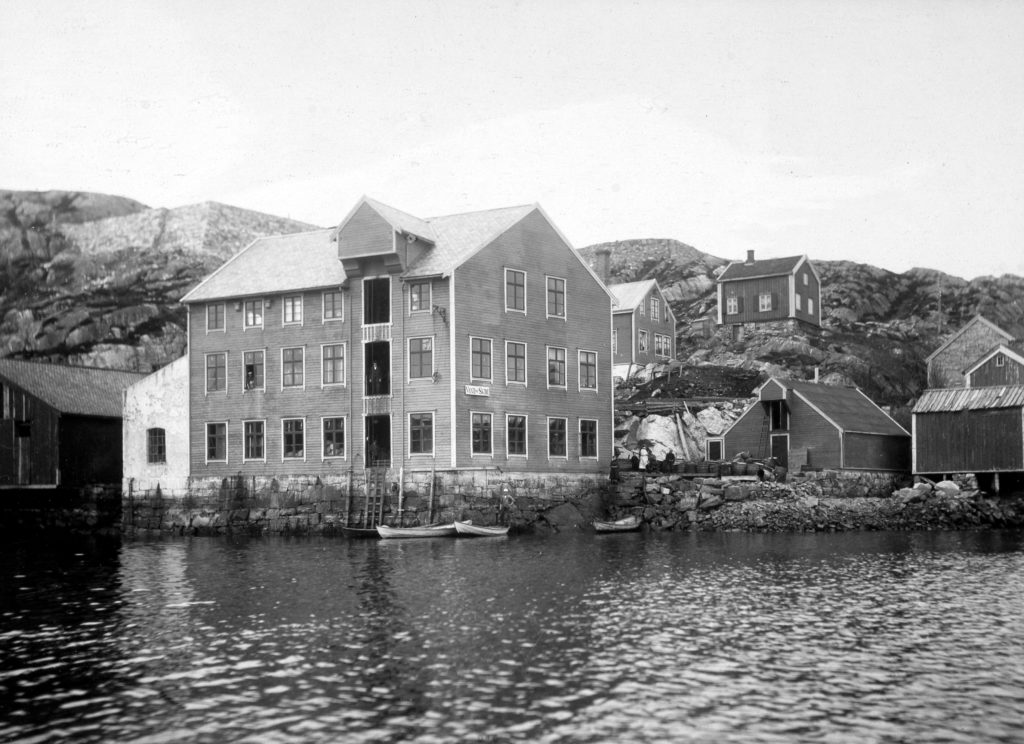

That included Lille-Fosen, which had no forest of its own but could ship timber in from the fjords. As a loading place, it was an export port and made good money from the tolls.

The 17th century became a golden age for Lille-Fosen. Timber sales went well and toll revenues were high. Forests in Sunnmøre and Romsdal to the south were over-felled, but part of Nordmøre’s woodland remained.

Reduced demand in 1700-80 gave the local forests a chance to recover, and timber exports from Kristiansund in the century’s final two decades were easily as good as in the 17th century.

The timber trade allowed Lille-Fosen to expand as loading place, but the contacts it provided with foreign markets laid the basis for an even bigger and more important commodity – fish.

While the timber trade was profitable, the latter product ensured that the settlement secured commercial town rights and the status of a municipality in 1742.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hoff, Randi Holden. “Avlet i synd og ondskap.” En sosial- og rettshistorisk undersøkelse av fødsler utenfor ekteskap i Kristiansund 1742-1801. Tingbokprosjektet, Oslo 1996: 30-31.

Fickle fortune

Fantastic catches of herring were made off Nordmøre for 22 years after 1736, helping to make Kristiansund Norway’s second-largest exporter of fish products after Bergen.

But the herring is fickle, and it failed to turn up in the spring of 1758 – and over the next few years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hoff, Randi Holden. “Avlet i synd og ondskap.” En sosial- og rettshistorisk undersøkelse av fødsler utenfor ekteskap i Kristiansund 1742-1801. Tingbokprosjektet, Oslo 1996: 31.

To the rescue

Klippfisk was more reliable. Preferably produced from cod, this form of dried and salted fish can also use haddock, ling, cusk or saithe. Lille-Fosen began exporting klippfisk in the 17th century, but a brief intermezzo meant that earnings were lost and the processing method forgotten.

It was not until the 1730s that the little settlement began producing dried and salted cod again, then under the auspices of British merchants who had both capital and expertise.

Unlike dried cod, the klippfisk process was introduced to Norway from abroad and is considerably more involved than straightforward drying. The fish must be split, salted and washed before being pressed and dried. This method was probably invented by Basque fishermen working off Newfoundland around 1500. Fosna has both a good climate and fine, level rocks suitable for drying klippfisk. Combined with its sheltered harbour and central location in the Leads, everything favoured the port.

Producing dried and salted cod calls for capital, and the question was how a relatively small town on the weatherbeaten west Norwegian coast could fund such an industry.

The Dano-Norwegian monarchy appreciated the importance of attracting both capital and know-how to Norway from abroad and accordingly gave privileges to foreign merchants. These were intended to help develop local industries.

Scottish and English entrepreneurs received exemptions from taxes and customs duties, and were allowed to take their wealth with them if they left Norway within 20 years. If they married a native, however, all these privileges were withdrawn.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arne Odd, Kristiansunds historie, vol 2, Fra lokal til nasjonal frigjøring 1742–1814, 1951: 37.

Many of the merchants indeed took their money with them and left Kristiansund after two decades. But they left the knowledge of the conservation method and an important network of traders in Europe and South America ¬– exactly as the king had intended.

Fish exports called for cargo vessels, and Kristiansund’s first shipyard was established in the 1760s. And local merchants began to become seriously involved in shipowning.[REMOVE]

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,Fotnote: Hoff, Randi Holden. “Avlet i synd og ondskap.” En sosial- og rettshistorisk undersøkelse av fødsler utenfor ekteskap i Kristiansund 1742-1801. Tingbokprosjektet, Oslo 1996: 33.

Klippfisk generated huge riches. Great fortunes became concentrated in a few hands and the biggest of them all, Nicolai H Knudtzon, ranked in the late 19th century as one of Norway’s wealthiest men.

Big social differences developed, with a small but enormously rich elite – known as the “klippfisk barons” – and a large and poverty-stricken underclass. The “barons” owned the whole production chain, from the fishing villages to the export ships, while the poor lived at times from hand to mouth.

Nevertheless, there were few signs of unrest among the latter. Most people seem to have been pleased to have work – even though it was often unstable, poorly paid and laborious.

The klippfisk industry had to cope with big fluctuations in international economic activity, and Kristiansund participated in both upturns and downturns. A sudden price fall in the Spanish market led in 1884 to a slump, stripping the big klippfisk exporters of their wealth and driving all but one into liquidation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Husby, Egil, En bank for bygd og by: Nordmøre sparebank 150 år: 1835-1985. 1985: 111. On the other hand, the 1914-18 war were years of increasing prosperity and Kristiansund consequently rose to become one of Norway’s most expensive towns. This proved a difficult time for its poorer residents.

The First World War over, demand for klippfisk sank and a long recession began. In 1921, the council had to ask the government for help because it could not pay its bills.

While the industry eventually began to recover during the 1930s, rising prosperity came to an abrupt halt when the Germans invaded in 1940. The attackers did their bit to remove the last remains of the golden age through an intensive bombing campaign over four days at the end of April. More than 800 houses were destroyed and the attractive town was left in ruins.

Ålesund takes the lead

Klippfisk once again came to the rescue, and Kristiansund accounted in 1955 for 75 per cent of all Norwegian exports of this commodity. Some 500-800 people worked in the sector.

But a dramatic change occurred between 1955 and 1960, as Ålesund surged ahead and acquired hegemony over klippfisk. Although the town had exported a lot of this product earlier, Kristiansund had always been the leader for these sales.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Williamsen, Odd W, Solnedgangsnæringa soltørking, Nordmøre Museum Foundation, http://www.nordmore.museum.no/bes%C3%B8k- oss/kristiansund/klippfiskmuseet/solnedgangsn%C3%A6ringa-solt%C3%B8rking.

Ålesund’s klippfisk exports rose steadily in the following years, and it accounted for no less than 80 per cent of all sales in 1977 with only 13 per cent coming from Kristiansund.

Several factors may have accounted for this southward shift. While Ålesund converted relatively early to artificial drying of the fish, for example, Kristiansund stuck with the sun.

This was a far more labour-intensive and time-consuming method, taking three-five weeks in the spring only and requiring about 80 workers. The artificial approach took five-six days, could continue year-round and needed five people.

In the post-war years, it was difficult to secure enough cheap labour to persist with sun-drying. The industrialisation of Norway made demands on the labour force.

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,Kristiansund had long lagged behind other Norwegian towns in terms of industrial development, primarily because supplies of water and electricity were insufficient.

The council now made a bigger commitment to frozen fish, since the herring shoals had once again returned and supported a fantastic fishery in 1955-70.

Filleting was a substantial industry in Kristiansund and Nordmøre for many years, with the town alone home to a number of companies headed by Norfinn and Heide.

This business provided employment for hundreds of women, but many fishing-related jobs disappeared in the 1970s and 1980s. Norfinn went into liquidation in 1988.

Power and water

Ålesund took over the klippfisk hegemony for a number of reasons, but access to cheap hydroelectricity was an important factor. While 11 local authorities in the Sunnmøre region joined forces to launch major hydropower projects, such low-cost energy was in much shorter supply in Kristiansund.

The town began using electricity in 1899, and the first large-scale hydropower development was Kristiansund Elektrisitetsverk’s Skar Kraftverk power station in Tingvoll during 1917–20. However, a lot of things went wrong with this project and it became much more expensive than planned. Its high cost put the local authority in a difficult financial position.

The other big problem for the town was fresh water supplies, with residents constantly complaining about pollution. A number of reservoirs were built in the town between 1855 and 1910, but they were too small and dried out during droughts.

A water main laid from Bolgavatnet lake at Frei in 1912 remained Kristiansund’s source of potable water right through to 1979. However, it was clear as early as 1945 that this was too small to meet demand. The price of fresh water was high.

Work began in the early 1970s to pipe water from Storvatnet lake in Tingvoll local authority. This was expensive, but necessary – water supplies were essential for both fishing and, later, offshore operations. Without them, the town would not have been chosen as an oil base.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Innvik, Petter E, Et fyrtårn i havgapet. Tidens Krav gjennom 100 år. 1906–2006. Tidens Krav 2006: 157.

Social conditions

Kristiansund’s population rose sharply after the town secured commercial rights – from 700 in 1742 to 1 429 by Norway’s first full census in 1769 and 1 979 in 1801.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hoff, Randi Holden, «Avlet i synd og ondskap.» En sosial- og rettshistorisk undersøkelse av fødsler utenfor ekteskap i Kristiansund 1742-1801. Tingbokprosjektet, Oslo 1996: 34 og http://www.wikiwand.com/no/Liste_over_norske_byer.

This rapid expansion was accompanied by cramped living conditions, poor hygiene and expensive housing. Tuberculosis, Spanish flu and other influenza epidemics claimed many lives.

Economic depressions, a big working class and lack of paid work led to wider class divisions and extensive poverty. Unemployment was high at times, and many relied on seasonal jobs.

While 15 per cent of the able-bodied population was out of work in 1900,[REMOVE]Fotnote: Innvik, Petter E, Et fyrtårn i havgapet. Tidens Krav gjennom 100 år. 1906–2006. Tidens Krav 2006: 12 this proportion rose even further in the 1920s and 30 per cent of men of working age were jobless at the peak.

Tax revenues declined and the local authority’s debt burden increased. Spending on poor relief rose, and accounted for 40 per cent of the municipal budget in the 1930s. The number of residents on welfare was far above the national average, but the amount paid per capita was below average.

Emigration to America was also high, with no less than 1 400 people crossing the Atlantic in 1875-1914. The annual number of emigrants fluctuated with the state of the economy.

The crisis also affected other parts of the Nordmøre region, with people living along the coast suffering direct want at times. Fishing families appear to have been hardest-hit.

Class distinctions were highly visible, with an enormously wealthy “klippfisk aristocracy” and an all-the-poorer working class. Nordmøre had more alcohol abuse than the rest of the county, and Kristiansund was the worst of its towns in this respect. The local newspaper, Tidens Krav, described the Kristiansund working class as among the least unionised in Norway and “some of the country’s most wretched wage slaves”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Innvik, Petter E, Et fyrtårn i havgapet. Tidens Krav gjennom 100 år. 1906–2006. Tidens Krav 2006: 24

Weak finances because of high unemployment, low tax revenues, mishandled power development and big class differences drove Kristiansund local authority into bankruptcy in 1932.

It was placed under central administration and a number of unpopular measures adopted. But the municipal debt was gradually written down and local self-government could be restored in 1935.

Infrastructure

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, , sundbåten, engelsk

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, , sundbåten, engelskKristiansund occupies three islands divided into four districts or land – Gomalandet, Kirkelandet, Nordlandet and Innlandet. The first two are joined by a narrow isthmus at the head of the bay and are therefore not separate islands.

As in so many Norwegian settlements, water has always been the most important transport artery. The Leads tied the country together, and Kristiansund’s islands were linked from 1876 by the “Sundbåtene” ferries.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Established on 18 November 1876, this passenger route between the four municipal districts is claimed to be one of the world’s oldest public transport services in continuous operation.

The 1920s witnessed the opening of a new era, when cars and buses began to compete with ship traffic. That applied particularly to the movement of people.

Suddenly, the fjords became a barrier. Settlements which had previously occupied key positions along the Leads became backwaters and Kristiansund found itself in the periphery.

A bridge linking Nordlandet with Gomalandet and Kirkelandet opened in 1936, but Innlandet remained without a road connection until 1936. It took almost 50 years to secure a bridge to the mainland. Some 12-15 000 people demonstrated for a Kristiansund-Frei link in 1976 – the largest mass rally in the town’s history.

kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,The following year, the public roads directorate in Møre og Romsdal was commissioned by the Storting (parliament) to lead planning work for this project.

But a further eight years passed before the Storting approved construction of the Krifast bridge in 1985. After four years of work, it opened on 20 August 1992.

The Atlantic Tunnel connecting Kristiansund to Averøy and thereby with Molde to the south was eventually opened in 2009. But Kristiansund lost its fight for a rail link. After the Rauma line opened in 1924, an extension to the town via Ålesund and Molde was considered.

But the railway never got further than to Åndalsnes, despite constant demands for an extension, and this issue is now regarded by most people as a dead letter.

The town only acquired a functioning airport in 1970 with the inauguration of the facility at Kvernberget (see Kvernberget – crucial for a future in oil. ).

kristiansunds tidligere historie, flyplass, helikopterbasen på kvernberget, engelsk

kristiansunds tidligere historie, flyplass, helikopterbasen på kvernberget, engelskDiversification

Although fish and fishing have played the central role in Kristiansund’s life, other industries increased steadily in importance as the 20th century advanced.

Shipbuilding became a leading sector in the town after 1945, but this business was also at the mercy of international economic developments.

Founded in 1876, the Storviks Mekaniske Verksted yard pioneered stern trawlers in the 1960s and helped turn Kristiansund into a shipbuilding town. It provided 600 jobs at peak as well as spin-offs.

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelskThe industry experienced a crisis around 1980 and Storvik joined forces with Sterkoder, the town’s other big yard. Work included repairs to the Byford Dolphin rig. But Storvik went bust in November 1981 at the cost of hundreds of jobs.

Established in 1916, Sterkoder Mek Verksted AS had its ups and downs like everything else in Kristiansund and went bankrupt in the 1960s when fishing entered a slump.

New owners took over in 1966, the future looked promising and the company expanded at record speed. When Storvik went into liquidation, Sterkoder acquired its facilities and a number of skilled workers secured new jobs.

The company initiated the big commitment to the oil industry. New subsidiaries were established and industrial sites planned, while a deepwater quay and a big shop to build sections for offshore use were built.

A partnership established with Norway’s Kværner group won many contracts from the construction of the Statfjord A platform in the mid-1970s.

In 1978, Sterkoder joined forces with French company UIE to form Sterkoder UIE and secured work on deliveries related to the Statfjord B and Valhall developments. After many big contracts in the early 1980s, the company found the middle of the decade challenging. Many workers had to be laid off in 1985-86, and the era of large offshore jobs at Sterkoder was effectively over by 1990. Finnish shipbuilder Wärtsilä acquired 50 per cent of the Sterkoder shares, and the two companies won a contract from Russia for 15 ships worth NOK 2 billion. But the jubilation was short-lived, with Wärtsilä Marine Industries AB going bankrupt in 1989.

Sterkoder received aid from the Ministry of Finance and Den norske Bank, with a funding package intended to provide six years of work for several hundred people plus sub-contractors. Den norske Bank worked to find stable owners, and Umoe-Ulltveit-Moe took over all the shares in 1991. That put Sterkoder in a shipyard group which completed the Russian order. But fresh problems built up, and the company consistently lost money. Constant new layoffs and redundancies ended with the liquidation of Umoe Sterkoder in 2002.

Soap and perfume

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,A few entrepreneurs founded the Aktieselskapet Goma Smørfabrikk factory in the Gomalandet district during 1900 in order to reduce the town’s dependence on fishing. An initial output of butter substitutes and margarine eventually expanded to include soap, detergents and steel wool soap pads.

The Såpefabrikken soap factory was established in 1932, and manufactured a large variety of cosmetic products in its Ello division. This was acquired in 1973 by Lilleborg, which became part of Orkla in 1986.

However, the latter decided to shut down the Kristiansund plant after 116 years of operation and transfer production to Falun in Sweden. The town lost 60 jobs and a whole industry.

Clothing

The garment business in Kristiansund goes back to 1887, but the oldest company ¬– Suveren – faced competition from low-cost countries in the 1970s and went bust in 1975.

Two other ready-to-wear manufacturers, Lanett Strømpefabrikk and Fosna Konfeksjonsfabrikk, had already disappeared by then. That left only Berserk Fabrikker, which survived until 1997.

Yet another medium-sized company with a high level of expertise thereby disappeared at a time of high unemployment and few jobs for women.

Education

The development of regional colleges began in Norway around 1970, with Møre og Romsdal acquiring two initially, in Molde and Volda respectively, and a third later in Ålesund.

General progress for Kristiansund and Nordmøre was severely hampered by the lack of a regional college, but neither town nor district made the same effort here as other parts of the county.

People in Kristiansund took the view that it was more important for youngsters to get a job and start earning money. A private college opened in 1986 by the Norwegian School of Management closed in 2004.

Significance of oil

Rebuilding Kristiansund after German bombers had flattened the town during four April days in 1940 was virtually complete by the late 1960s. In 1970, it also acquired its own airport and an important communication artery was thereby in place. The four urban districts were also linked, but the bridge to mainland still lay well in the future.

Kristiansund has always been affected by the international business cycle, and unemployment was again high in 1970. The town’s most important trade commodity had virtually vanished.

Ålesund took over the production and export of klippfisk, and herring no longer spawned along the Møre coast. The clothing industry was on its last legs and the soap factory was sold to east Norwegian owners. As so often before, the locals saw the opportunity in 1970 to acquire a new industry and the jobs which went with it. They laid a plan and succeeded through systematic and patient work.

This first bore fruit when Kristiansund was chosen as the base for oil exploration on the Møre coast, and later when Shell picked it in 1989 as the operations centre for the first producing field in the Norwegian Sea – Draugen.

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, flyfoto, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, flyfoto, engelsk,