Royal Dutch Shell – a brief history

Now a multinational company with its head office in the Hague and its business address in London, Royal Dutch Shell started life in 1907 as an alliance between Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and Britain’s Shell Transport and Trading Company. This is the story of how the group grew into one of the world’s largest enterprises, but also about its two founders – Marcus Samuel Jr and Henri Deterding.

While the first of this pair was an ambitious Londoner of Jewish origin from the East End, the other hailed from the Netherlands and had a bent for details and figures.

Samuel Samuel & Co

This enterprise was founded in Yokohama, Japan, in 1878 as an international trading company. Samuel Samuel then established Rising Sun Petroleum Co (later Shell Petroleum) in 1900 as an independent petroleum arm distributing candles and lamp oil (kerosene). Soon afterwards, this company merged with the Royal Dutch/Shell group.

Dawning globalisation

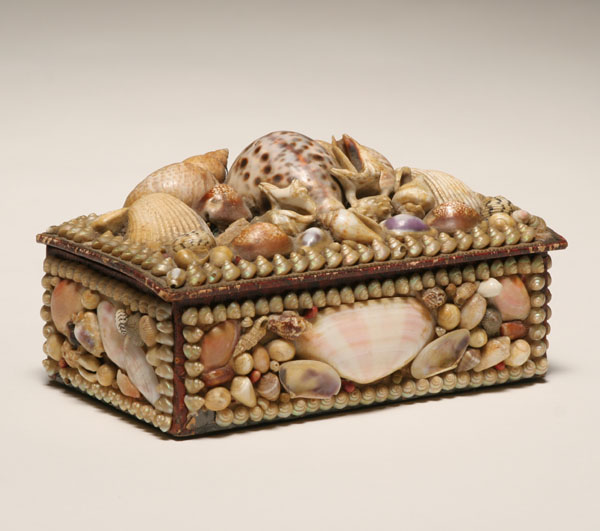

It all started in 1833 when Marcus Samuel Sr began a small business in the East End, dealing in antiques and curiosities as well as painted seashells, fashionable in Victorian Britain.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 32.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The enterprise was lucrative, and grew into a flourishing import-export company. Samuel organised bilateral trade between the UK and the Far East. Textiles and machinery for industrial development were shipped from the UK in exchange for rice, coal, silk, copper and porcelain. Trading partners multiplied, and Samuel was soon dealing globally in food, sugar, flour – and shells.

He was succeeded on his death in 1870 by sons Marcus Jr and Samuel. Their most important inheritance was a network of trusted agents in the Far East as well as other business contacts.

They established two firms in 1878 – Marcus Samuel & Company in London and Samuel Samuel & Company in Japan. Samuel, the older of the pair, moved to Japan and remained there for a decade. The second half of the 19th century was a time of rapid technological progress and dawning globalisation, with steel and steam as perhaps the key combination. Railways and steamships revolutionised travel and economics. New types of vessel which were larger, stronger and faster than before shrank the world.[REMOVE]Fotnote: An important person in this context was Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a British engineer involved in a number of UK construction projects – including bridges, steamers, railways and tunnels. He is best known for laying the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London and building SS Great Britain, which ranked at the time as the largest ship ever launched.

The wireless telegraph also simplified contact between the UK, India, China, Singapore, Japan and Australia. And the Suez Canal, opened in 1869, gave European freighters a direct route to Far Eastern markets.

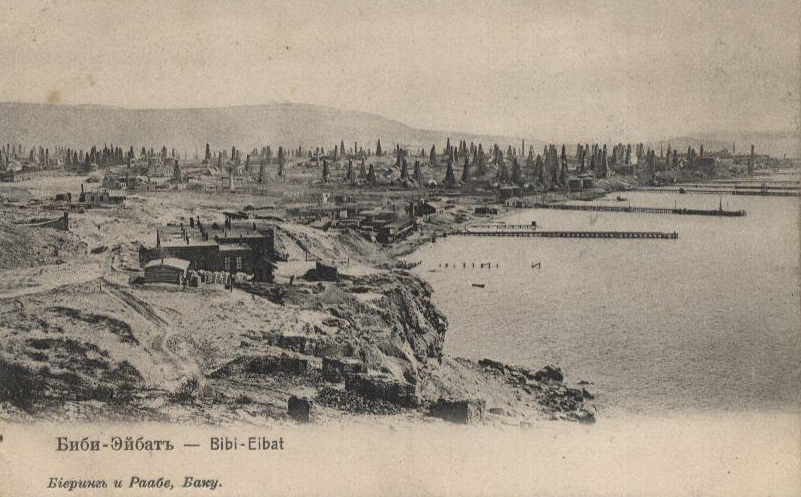

Another significant innovation for Shell’s history was the refining of crude oil into kerosene (paraffin), primarily in Baku (then in Russia and today part of Azerbaijan).

Lamps burning this hydrocarbon product quickly became the preferred source of lighting in European and North American homes and created a new trade commodity.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Abraham Pineo Gesner was a doctor and geologist who is regarded as the pioneer of the modern oil industry. His research into minerals led in 1846 to the discovery of a process for creating a type of coal-based fuel. Known as kerosene or coal oil, this new product burnt more cleanly and was cheaper than existing whale or plant oils. The refining process was extended to petroleum in order to produce paraffin.

Marcus Samuel Jr took his first tentative steps into oil trading when he purchased small quantities of paraffin from Standard Oil[REMOVE]Fotnote: Standard Oil Company was the biggest organisation of oil refineries in US history. Founded in 1870 by John D Rockefeller and others, it was dissolved in 1911. https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Oil. US oil production got seriously under way in 1859 with the Titusville discovery in Pennsylvania. and Jardine Matheson for sale in Japan.

He expanded this business by selling Russian crude from Baku for the Rothschild family to Far Eastern countries, thereby breaching the monopoly held by Standard Oil.

Founded by John D Rockefeller in 1870, the latter company had secured control over most US oil production and transport by 1890. At peak, it had 90 per cent of the world’s oil refining.

Samuel visited Baku for the first time in 1890, along with the Black Sea port of Batumi where Russian crude was exported to Europe. He was very impressed by the scale of this traffic, and saw the potential for trading paraffin and the big market offered by the Far East.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh.

During the 1870s, the Russian Tsar had abolished the state monopoly over petroleum and the oil hunters poured into Baku. They modernised exploration, production and – not least – transport methods.

The most important players were the Swedish Nobel brothers, Robert and Ludwig, and the Rothschilds. The latter were and are one of the world’s richest families. Among their other accomplishments, the Nobels laid pipelines from wells to refineries as well as designing and building a small oil tanker – the Zoroaster – to ship paraffin across the Caspian.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The Rothschilds came up with a different solution by building a railway line from Baku to Batumi. Their Bnito company could thereby outcompete Standard Oil in the European market.

Used for both lighting and heating, paraffin was the only crude oil fraction of interest at that time. The increasingly industrialised world paid growing attention in coal as an energy source.

As a result, a market barely existed for oil as a transport fuel. Its heaviest components were discarded while the associated gas was flared. Standard Oil had established a virtual monopoly of paraffin sales in Asia. Freighting American paraffin directly to this market by sea was quicker and cheaper than sending Russian production by land, which needed a big investment in railways.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The alternative for the Nobel brothers or the Rothschilds was the sea route from the Black Sea around the Cape of Good Hope, a long and dangerous voyage.

But the Rothschilds nevertheless had plans to compete with Standard Oil in the Asian market. They turned to Marcus Samuel, who had good contacts and a network of agents in the Far East.He saw that the solution to the transport problem lay with the Suez Canal, which had simplified and not least reduced the cost of maritime freight between Europe and Asia since 1869.

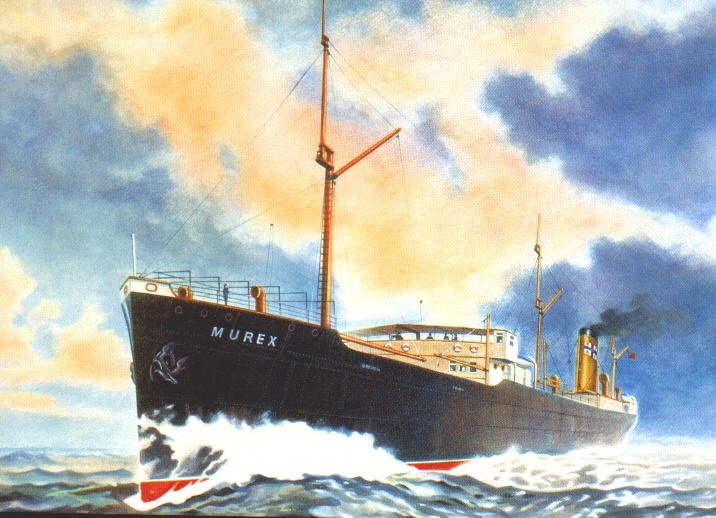

However, safety concerns meant that ships carrying oil were banned from the canal. So Marcus got British naval architect Fortescue Flannery to design a safer vessel. This Murex tanker was also longer than earlier types.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The work was crowned with success on 24 August 1892 when Murex completed its maiden voyage through the canal with 4 000 tonnes of Russian paraffin bought from Bnito and shipped to Singapore.

Lamp oil from Russia could now compete on price with Standard Oil’s US product. Prices fell, and Marcus Samuel rapidly increased his market share. These new tankers also had the advantage that – unlike earlier oil carriers to the Far East – they could carry other products such as food on the return leg rather than sailing home empty.

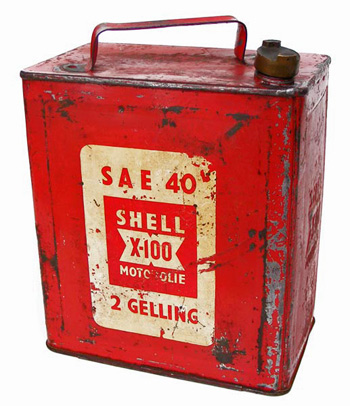

Marcus Samuel shipped paraffin in bulk, but Asians wanted it in cans. Standard Oil’s blue containers could be seen everywhere in every kind of application, from roofs and doors to saucepans. Samuel’s strength laying in being innovative and decisive. He quickly had tinplate shipped east while building factories to make cans. Red was quickly adopted as the colour. Competition between Standard Oil and Shell now became directly visible on roofs, doors and all the other places where the cans were used.

The Shell brand

Marcus Samuel established the “Shell” Transport and Trading Company Limited (the quotation marks were part of the legal name, but at dropped hereafter) on 18 October 1987.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The shares were distributed between Marcus (with 7 500), Samuel (4 500) and eight other investors who received proportionate holdings. It was also determined that Marcus and Samuel would have five votes for each of their shares, compared with one per share for the others. That gave Marcus full control. Established because of uncertainty over oil deliveries, the company’s name was chosen in homage to Marcus Sr’s first trade commodity and a shell served as the logo.

Marcus owned no oil wells or refineries, and his goal was to secure its own crude and gain control over every stage from drilling to refining, transport, distribution and sales.

Shell Transport made a discovery in Borneo in 1897, but this oil contained little paraffin. Instead, it comprised a lot of petrol and toluene.

The latter is a petroleum fraction used in solvents, dyes, pharmaceuticals, explosives and other applications. Neither it nor petrol had much of a market at the time, but both were to play a key role within a few years.

Royal Dutch and Deterding

NV Koninklijke Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Petroleumbronnen in Nederlandsch-Indie, abbreviated to Royal Dutch, was established by Aeilko Zijlker in the Hague in 1890.

Its full name in English is Royal Dutch Company for Working of Petroleum Wells in the Dutch Indies. This was not officially simplified to Royal Dutch Petroleum Company until 1949.

Zijlker, a former plantation owner with the East Sumatra Tobacco Company, had secured a concession to drill for oil on Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). He made a big discovery there in 1885, but died suddenly in December 1990 and was replaced by J B August Kessler. The company’s first brand was launched by Kessler as Crown Oil.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,However, the sales and distribution network proved inadequate and marketing was weak. Things went even worse in 1897, when the Sumatran wells began to produce water alongside the oil. Within three months, they were dry and Royal Dutch was forced to start buying Russian paraffin.

A 30-year-old bookkeeper, Henri Deterding, had joined the company in 1896. As early as 1901, he became its chief executive when Kessler died and proved an outstanding entrepreneur.

Deploying strategic vision and financial awareness, his ambition was to build an enterprise which could measure itself against the world’s largest petroleum company ¬– Standard Oil.

To compete with Rockefeller and Shell Transport, Royal Dutch began to construct its own crude oil carriers and storage tanks, and established a sales organisation.

An emerging merger

The oil industry was changing rapidly at the start of the 20th century, having become complex and politicised. To resist takeover moves against both companies by Standard Oil, Marcus Samuel offered Royal Dutch a defensive pact which would mean no undercutting of each other in the Far East.

A new idea had gripped him at this time which would claim his attention for the next 15 years. Instead of refining oil into paraffin, he would use it as fuel in Shell’s own tanker fleet.

The Nobel brothers had previously demonstrated that this was possible with their small tankers on the Caspian, and the idea gathered momentum. If it could be done on a large tanker, why not use oil instead of coal in the British merchant marine – the world’s largest? But the fight to win acceptance for this innovative concept cost Marcus pain, humiliation and big losses before he ultimately succeeded.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,He decided that Shell would be in the forefront of motor fuels, started building refineries for such products, expanded the company fleet and bought large amounts of oil where possible.

Prospects looked good for Shell Transport and Marcus – until a wave of events washed over them, including destruction of storage tanks during China’s anti-Western Boxer rebellion in 1899-1901.

The Boer War between Britain and ex-Dutch settlers in South Africa also destabilised a brand new market. UK forces suffered three damaging defeats during Black Week in December 1899, which boosted Dutch nationalist sentiment worldwide to the benefit of Royal Dutch.

Investments in India were wiped out when Burmah Oil[REMOVE]Fotnote: A Scottish oil company established in 1886. gained control of the paraffin market there. And, to top it all, world trade suffered a general slump and shipping rates were falling. The future looked unpromising. To keep its four biggest tankers working, Shell began buying Romanian paraffin for worldwide sale.

This left Shell with big lamp oil stocks when Standard Oil decided to dump cheap paraffin on the European market as US demand for this product lagged behind rising petrol consumption in cars.

Electricity was now the most important source of lighting and heating, outcompeting paraffin, and the price of the latter slumped. Shell Transport was particularly hard hit.

An event then occurred which promised to rescue Marcus and the company – a 40-metre-high geyser of oil rose above Spindletop in Texas on 10 January 1901.

The Shell boss saw this as a fantastic opportunity, and entered into a 21-year deal to freight Texan oil. But this venture ended disastrously when overproduction destroyed the well and production sank dramatically within a few years.

Nor did the downturn stop there. One of Shell’s tankers, laden with paraffin, went aground in the Suez Canal and another of its ships attempted a rescue. While being pumped from the grounded vessel, the oil caught fire and both ships were burnt out. Shell lost its right to carry motor fuel in bulk through the canal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 87.

Shell Transport was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1903 when it entered into a collaboration with Royal Dutch to protect both from Standard Oil’s dominance. They formed the Asiatic Petroleum Company Ltd with the Rothschilds as the third partner.

Marcus became chair and Deterding chief executive, and the new venture collaborated in all Far Eastern markets. But it was confined to that region – Shell and Royal Dutch continued to compete everywhere else. Shell Transport staggered from crisis to crisis, while Asiatic took wing under Deterding’s leadership.

Royal Dutch made huge profits over the next three years from petrol, while Shell was less fortunate with its commitment to heating oil. Demand for this product still lay in the future.

As mentioned above, Shell’s Borneo oil was rich in toluene and petrol but poor in paraffin. To find markets for the crude, Marcus made a fresh effort to sell fuel oil to the British navy – only to be rejected again. Britain’s military authorities gave an equally firm refusal to offers of toluene as an important ingredient in the explosive trinitrotoluene (TNT). They felt the quality was inadequate, and preferred to extract toluene from British coal.

However, both Germany and France were keen to buy and the contracts were so large that Shell could build a toluene plant at Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Despite their size, these deals were not enough to save the company. Only one way out remained – Marcus went to Deterding and proposed a merger on the Asiatic Petroleum model.

Shell’s financial position was so weak that Deterding could dictate the terms for this transaction. Royal Dutch got 60 per cent, while Shell Transport had to rest content with 40.

Marcus had no choice but to accept. Shell became a holding company under his control. To ensure that Royal Dutch led the group for Shell’s benefit as well, it bought shares in the new holding company.

Multifaceted

The resulting Royal Dutch/Shell group has never existed as a legal entity. Neither Royal Dutch nor Shell Transport ceased to exist when they entered a formal alliance on 1 January 1907.

They unified their interests but retained separate identities. Each thereby became a holding company rather than an operational enterprise. Petroleum exploration, production and sales continued to be pursued by a number of operating units, with Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company in London and Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij in the Hague as the first of these. They were specially established for the purpose, and took over virtually all physical assets in the holding companies. Anglo-Saxon handled oil storage, while Bataafsche ran oil fields and refineries.

Both enterprises were wholly owned by the holding companies in the 60-40 proportion established in the terms for the merger. Royal Dutch and Shell Transport also appeared in the organisation charts below three other holding companies: Shell Petroleum Company Ltd in London, Shell Petroleum NV in the Netherlands and Shell Petroleum Inc in the USA.

The number of operating companies increased rapidly, and dozens of separate legal entities were established worldwide, some wholly owned and others as joint ventures. Shell Transport and Royal Dutch also retained separate head offices in London and the Hague. Joint financial and commercial matters were to be dealt with in London, while significant technical issues fell to the Hague. The hierarchy was topped by a committee of managing directors.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 102.

As will become clear below, this company structure had consequences for the way it was run and communicated with public opinion.

The organisational model allegedly encouraged inertia in the system, poor communication, and what a Financial Times analyst called “regrettable decisions”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Financial Times, 9 October 2004. “Shell to embark on radical overhaul”.

Age of the car

The group made rapid progress under Deterding’s leadership. Total assets for Royal Dutch and Shell Transport grew more than 250 per cent between 1907 and 1914. It was decided to expand into new areas, acquire new sources of crude oil, and place the rising refinery business under central control in order to meeting growing demand worldwide.

The group secured control of major production interests in Romania (1906), Russia (1910), Egypt (1911), Venezuela (1913) and Trinidad (1914), while holdings in Indonesia were extended.

Standard Oil’s core market was also penetrated with the creation of Roxana Petroleum Company in 1912 to operate in Oklahoma. The British-American Gasoline Company in California was acquired the following year, while oil-producing tracts were purchased and operations widened in central USA. By the end of 1915, Royal Dutch/Shell was producing almost six million barrels of crude per annum in America.

In addition, the group extended its distribution network to many countries. It came to Norway in October 1912 as Norsk Engelsk Mineralolie Aktieselskap (Nemak). See Shell in Norway.

The number of cars and motorbikes on the roads in the western world expanded swiftly after 1900, leading to a concomitant rise in demand for petrol. That coincided with a dramatic decline in paraffin sales as the incandescent lightbulb and electricity spread. Aviation fuel also began to become profitable.

Not least, the British navy finally recognised the advantages of oil-fired ships, which were recommended by a royal commission in 1912. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had been in Morocco during the crisis there and observed the oil-fuelled German warships. He had been deeply impressed by their speed. Britain’s coal-powered naval vessels could only reach a top speed of 10 knots, compared with 35 for their German rivals.

Marcus saw his chance, and pressed Churchill to convert the navy to oil. Although only small quantities of fuel were initially bought from Shell, these purchases pointed to the future.[REMOVE]Fotnote: BBC, 31 August 2016. Planet Oil. The Treasure That Conquered the World. Episode 1.

Four months into the First World War, the UK was almost out of TNT and turned to Marcus. He solved the problem in great secrecy by moving the toluene factory from Rotterdam to Britain. The company also built a separate nitrate plant to utilise the toluene in manufacturing 450 tonnes of TNT per month. Shell constantly built new factories, and was also the only supplier of aviation fuel.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 105.

Where to find oil?

The problem for the UK was that it had a lot of domestic coal but oil lay far away in the Middle East, Indonesia and the USA. British interests had found petroleum in Persia (now Iran) in 1909, and the largest oil deal in world history was signed in 1914. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company secured an exclusive contract with the British navy, but on one condition – the UK would own 51 per cent of the shares. This was the first case of state ownership in an oil company. Anglo-Persian was the forerunner of today’s BP.

The Great War

Although the 1914-18 war produced mixed results for the Shell group, it helped to shape the new enterprise. The German invasion of Romania in 1916 destroyed 17 per cent of the company’s production capacity in a couple of days.

All its assets in Russia were confiscated after the revolution[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.shell.com/about-us/who-we-are/the-early-20th-century.html, while equipment-related difficulties meant that production in Venezuela was delayed until late in the conflict.

British civil servants and ministers accused the company of being pro-German and supplying the enemy with oil through subsidiaries in neutral countries. Efforts were made to merge the company with Anglo-Persian, Burmah Oil or other UK interests in order to secure British ownership.

These attempts failed and, despite its different owners, the group played an important role in the Allied war effort. On the positive side, holdings in the USA and Far East were expanded.

One important contribution by the Shell group to the Allies took the form of fuel deliveries to the British forces and, as noted above, it was the sole supplier of aviation fuel. Eighty per cent of the British army’s TNT hailed from the group’s factories. And it put all its vessels at the disposal of the British fleet. This improved Shell’s reputation and Deterding – who had been nicknamed the “Napoleon of Oil” – was made a Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire after the war.

(pic)

British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown used Shell aviation fuel in their historic non-stop flight over the Atlantic in 1919.

Rise and fall

Britons Alcock and Brown used fuel from Shell for the first non-stop flight over the Atlantic in 1919. This fact was exploited for all it was worth in the group’s marketing.

The following decade was characterised by growth, with the whole oil industry expanding through increased sales of cars and rising demand for motor fuel.

Shell also made big profits from new oil finds in California, Venezuela and the Middle East, and became involved in chemicals through the Dutch NV Mekog and Shell Chemical Company in the USA. Both produced nitrogen-based straight fertilisers.

The group also experienced notable growth in its refinery operations, and a number of new facilities were constructed in this part of the business.

Bunkering stations were expanded in ports worldwide, and Shell products became well known. Output steadily increased and new subsidiaries were established.

At the end of the 1920s, Shell ranked as the world’s leading oil company and accounted for 11 per cent of global crude production. It also owned 10 per cent of world tanker tonnage.

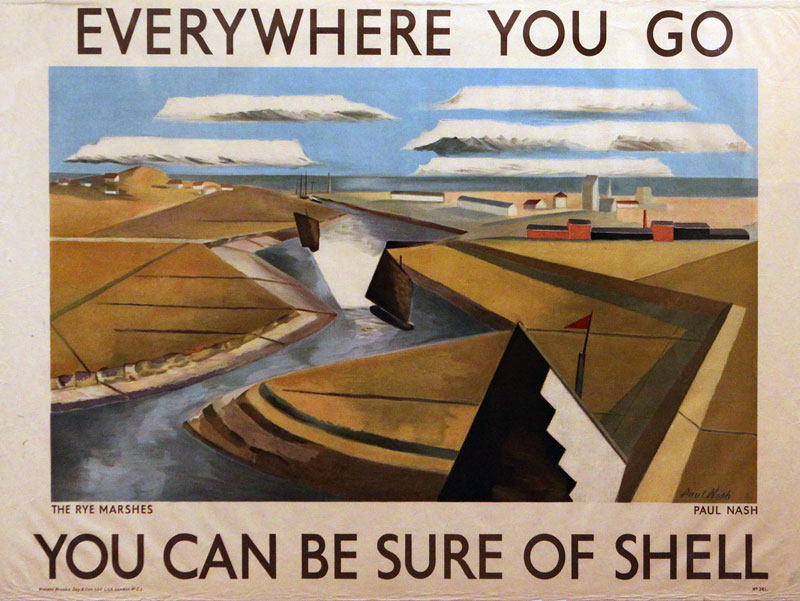

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,The group had given weight to marketing and advertising from an early stage, conveying themes of power, cleanliness, reliability and modernity under the slogan “You can be sure of Shell”. These aimed to create a green, comfortable and secure world embodied in clean products. Many of its advertisements have become classics.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.shell.com/about-us/who-we-are/the-early-20th-century.html.

Another aspect of these marketing efforts was the development of the global network of service stations which helped to build the group’s reputation. Shell was also a pioneer in sponsoring sports events, particularly motor racing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Olsen, Olav Søvik (2007). Rapportering og revisjon av olje- og gassreserver med utgangspunkt i Shell-skandalen 2004. Unpublished MSc thesis, Norwegian School of Economics.

Marcus Samuel Jr did not experience the whole of this expansive period. He retired in 1920, and died on 16 January 1927.

Depression and recovery

The Great Depression which began in 1929 forced Shell – like the rest of the industry – to downsize and cut costs. Apart from unstable oil prices, the sector was hit by overcapacity.

Deterding had built up Royal Dutch and then the merged group over 30 years into one of the world’s largest and most powerful enterprises. By the mid-1930s, however, his leadership abilities were beginning to be questioned. He was forced to resign at the age of 70 in 1936 after planning to sell a year’s oil production on credit to Germany’s Nazi government.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_Deterding

Along with financial support to both Hitler and Mussolini, this reflected his sympathies for fascism and Nazism. He died in February 1939, not long before the Second World War broke out.

A new war and its consequences

The German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940 meant the head offices of the Dutch companies were transferred to the Dutch West Indies, while staff moved to London. Major assets in the Far East were destroyed during the fighting, while the important oil fields in Romania were also lost.

Shell once again played a major role in the Allied war effort. The US refineries were crucially important, particularly for producing large volumes of high-octane aviation fuel. The Shell Chemical Company manufactured butadiene, an important component in the artificial rubber used for tyres and in industry.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The Japanese occupation of Malaysia halted supplies of natural rubber and prompted the development and manufacturing of the artificial product from petroleum.

All the group’s tankers were requisitioned by the British government, and Shell lost 87 of its ships in the course of the conflict. Once peace had been restored, major efforts were made to repair the damage to Shell’s installations. A great need existed to expand output, transport and refinery facilities.

The 1950s and 1960s were a golden age for the oil companies. Demand for their products rose steadily. A growing number of cars meant escalating fuel consumption. Shell delivered almost a seventh of the world’s oil products in this period.

After Deterding’s departure in 1936, the group had been run by a committee without any clear leader figure. That remained the case right up to 2005.

But other changes were introduced. During the 1960s, it was decided that the subsidiaries and companies in each country should be given greater independence. Local people were to be recruited to all positions, including the top jobs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.shell.com/about-us/who-we-are/1960s-to-the-1980s.html

Secure transport was crucial. Egypt’s closure of the Suez Canal at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967 sealed this important transport artery for eight years, until 1975. That in turn opened the way for the supertanker. To ensure deliveries worldwide, Shell invested heavily in new and larger ships and built special carriers for liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Apart from oil and gas, a third important product shaped the group’s history in this period – the rapid growth in chemicals production after 1945. Over the next 20 years, several hundred compounds were developed in more than 30 locations.

Shell also expanded its operations to encompass coal and metals. It became one of the world’s biggest petrochemicals manufacturers as well as a leading supplier of pesticides and health products for animals.

NV Neerlandse Aardolie Maatschappij (NAM), a joint Shell and Esso exploration venture, made one of the world’s biggest natural gas discoveries in 1959 at Groningen in the Netherlands.

Production began in 1963, and the field was supplying half the natural gas consumed in Europe by the early 1970s. Shell had started producing this commodity in its own neighbourhood.

Geological investigations demonstrated that similar sub-surface formations were to be found offshore, and the group’s search for hydrocarbons was extended to the North Sea.

It formed a 50-50 joint venture with Esso in 1964 to explore for oil and gas on the UK continental shelf, serving as operator under the Shell UK Exploration & Production (Shell Expro) banner.

During the 1970s, the North Sea became a significant arena for the petroleum sector, with big oil and gas discoveries in an extremely challenging operational and financial setting.

Exploration and production in these waters became a major activity for Shell, which invested substantially in new technology for use in one of the world’s toughest sea areas.

Honesty, integrity and respect for people[REMOVE]Fotnote: Shell’s core values, according to its own website. http://www.shell.com/about-us/our-values.html.

The oil industry also has a downside which the Shell group would experience directly, with pressure from external bodies increasing on the whole sector. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the human rights movement played an ever-increasing role on the international scene from the 1970s.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The 1967-70 Biafran war in Nigeria is regarded as the starting point for modern humanitarian work, and initiated the first major international solidarity campaign.

Environmental groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth were established during this period, and put pollution on the agenda.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rachel Louise Carson (1907-64) is regarded by many as the most important figure in the early environmental movement. Her 1962 book The Silent Spring played a significant role in the foundation of a broad-based American green crusade. The media also changed, with direct transmissions on TV, news spreading quickly, and increasingly sophisticated use of information channels by interest organisations and groups.

Shell found its reputation under challenge. Oil sales to countries with apartheid regimes and other involvement in there drew attention first, followed by major environmental scandals. The group’s oil deliveries to Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) topped the news agenda in 1976. This issue dated back to 1964, when the white minority administration began to demand independence.

At that time, the UK’s policy was not to make any of its former colonies in Africa independent without the introduction of majority African rule. The white settlers in Southern Rhodesia, led by prime minister Ian Smith, nevertheless declared independence unilaterally in 1966 and introduced an apartheid regime. This action was defined as rebellion by the UK, and the British Commonwealth introduced economic sanctions – including an oil embargo. The UN followed up with similar reactions in 1968.

Such sanctions had little effect, and by 1976 the white settlers remained in power with no shortage of oil. These supplies turned out to come in part from Shell and BP via South Africa and Mozambique.

Why and how these sales were carried out remain a matter of disagreement, but the issue had a negative effect on the reputation of the two oil majors.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Read more in Keetie Sluyterman (2007) Keeping Competitive in Turbulent Markets, 1973-2007. A History of Royal Dutch Shell, volume 3: 314-318. And matters did not stop there. The Shell group was also subject to substantial criticism because of its investment in neighbouring South Africa.

A number of organisations had started a campaign in the early 1970s against what they viewed as Shell’s support for the apartheid regime. But this really exploded in the media worldwide during the mid-1980s, and a global crusade against the group began in 1985. Pressure to pull out of South Africa grew particularly in the USA.

A media campaign urged consumers to cut up their Shell cards and refuse to buy petrol at the group’s service stations. Similar drives were launched in Europe.

Local authorities were urged to reject tenders from Shell. A number in Norway refused to deal with it, which had a direct impact on operating the Draugen field. See the article on ….

Shell got through this period without major financial loss, but was seriously concerned about the overwhelmingly negative coverage. The group’s reputation had been weakened, and it began to be clear that the decentralised corporate structure was creating problems.

Top management in the Hague and London were not informed of decisions taken by the autonomous South African subsidiary. It did not know enough about local conditions to adjust or terminate trade with the regime. Nor could it comment on behalf of the group and its own subsidiary. Shell’s basic policy was to avoid publicity but preferably to work through quiet diplomacy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Keetie Sluyterman (2007) Keeping Competitive in Turbulent Markets, 1973-2007. A History of Royal Dutch Shell, volume 3: 319.

This approach now began to be questioned. Departments and subordinate companies were encouraged to engage in dialogue with the general public, pressure groups, unions and universities, and to keep head-office staff informed.

Employees were also under continuous pressure from family and friends to respond to questions about the group.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Keetie Sluyterman (2007) Keeping Competitive in Turbulent Markets, 1973-2007. A History of Royal Dutch Shell, volume 3: 330.

Involvement in countries with controversial forms of government was not the only source of reputational problems for the Shell group. The environment also appeared on the agenda.

The wreck of Amoco Cadiz in 1978 generated massive headlines. Technical problems caused this tanker to pile up on the French coast and pollute 200 kilometres of shoreline with 240 000 tonnes of crude – the biggest spill of its kind until then.

Although Amoco owned the ship, the cargo belonged to Shell. Condemnation was particularly sharp in France, and the group was exposed to hostile and sometimes violent action.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Keetie Sluyterman (2007) Keeping Competitive in Turbulent Markets, 1973-2007. A History of Royal Dutch Shell, volume 3: 332. The criticism focused on the way Shell discharged its social responsibility.

The group turned out to have made little progress in understanding and dealing with campaigners when the redundant Brent Spar loading buoy came to be removed in 1990.

Shell again suffered massive criticism for its approach to corporate social responsibility after Shell Expro[REMOVE]Fotnote: The joint venture with Esso which operated in the UK North Sea. resolved in 1991 to remove the buoy from the Brent field in the UK North Sea.

Following a number of independent analyses which took account of safety, financial, technical and environmental factors, the company decided that sinking in deep water was the best solution. Scrapping on land would be more expensive and involve greater safety risks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 335. The British government concurred, and the group received permission in 1995 to sink the buoy in the Atlantic.

But Greenpeace did not agree. Nor was it consulted in the decision process, even though openness to and dialogue with interest organisations was part of Shell’s new strategy. The environmental group decided to launch a campaign against the principle of dumping installations at sea, with a special focus on Brent Spar, and made conscious use of the media.

Its simple message was that the industry could not use the oceans as a rubbish tip, just as others were banned from throwing old cars into the sea. Greenpeace occupied Brent Spar for three weeks in June 1995 under massive media coverage. Consumers responded by starting a boycott of Shell’s service stations. Shell Expro ignored the campaign, and the buoy began being towed north-westwards towards the Atlantic in June. Greenpeace responded with phase two of its media campaign.

Although the environmental organisation has since admitted that it exaggerated the amount of toxic waste on Brent Spar, that was no help to Shell at the time.

The group reversed its decision, and announced on 20 June that the buoy would not be sunk but taken to land. Nevertheless, it remained convinced that sinking was the best and safest answer.

British premier John Major, who had given the green light to sink Brent Spar, described Shell as “wimps” for surrendering to pressure.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 338. The buoy was towed to Norway, disassembled and used as a quay.

This issue demonstrated that popular opinion had a substantial effect, and that Shell had to learn to involve external views in its decisions. Feelings and beliefs could have just as much influence on the group’s “licence to operate” as hard facts.

Shell demonstrated once again that it spoke with several voices. While Shell UK had defended the ocean dumping, the group’s German arm expressed doubt that this was the right decision. The problem remained the decentralised corporate structure and local autonomy. Shell as a group came across as weak and divided. Brent Spar showed that it needed better internal communication and coordination on important political decisions.

Deadly delta

Shell hoped to rebuild a reputation as a reliable and green group. Although progress was being made, other parts of its business now came under the activist spotlight. Environmental and human rights campaigners made common cause over Shell in Nigeria, and the group faced massive worldwide reactions in parallel with the Brent Spar issue in 1995.

Oil production in the Niger delta was already a source of international contention, and Shell’s activities were not least a topic of debate. The media had begun investigating these operations a few years earlier, and a campaign began in 1990 on the difficult conditions faced by the Ogoni people and the environmental damage done to their homeland in the delta.

A crusade was launched against the Nigerian government and the oil companies in the country by the Movement of the Survival of the Ogoni People (Mosop).

This human rights group maintained that their lands were being plundered, with government and companies extracting billions of dollars per year while the locals got nothing for their resources.

They were left to poverty and a damaged environment. Mosop now demanded independence for Ogoniland and control over the area’s resources. Shell collaborated closely with the Nigerian national oil company, and thereby gave indirect support to the country’s military regime through revenues from oil production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 343. In the group’s view, how this money was used fell outside its ambit.

Critics claimed that Shell collaborated in plundering the country’s resources while leaving the delta dwellers to poverty, unemployment, pollution and consequent ill-health. Violent demonstrations took place. A lengthy conflict between the Ogoni and the military regime ended with the execution of nine Mosop leaders.

This outcome attracted great international attention, not least because one of those killed was the world-renowned author and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. After the executions, Shell came under attack from all sides – the media, NGOs, pressure groups and investors. Many critics rejected the group’s view that it could not interfere in the way Nigeria was governed or how its legal system functioned.

In their view, Shell should have used its influence in the country to prevent the executions. They argued that profit was being put before human rights.

The Ogoni issue did not lead to the same immediate drop in revenues as the Brent Spar case, but had a very negative impact on the group’s reputation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Cummins, Ian and Beasant, John (2005). Shell Shock. The secrets and spin of an oil giant, Edinburgh: 355.

From the mid-1990s, the key question for Shell was how it could operate in line with its business principles under military regimes which used force against their own people and distributed oil wealth unequally. This process initiated a shift towards accepting greater corporate responsibility for human rights and sustainable development.

The violence which developed and the threats to the company prompted Shell to pull out of the Niger delta in 1993. But the pipelines across the country remained.

Oil spills occurred regularly, partly because of old and damaged facilities and partly as a result of sabotage and theft. The spills helped to pollute drinking water, farmland and fishing grounds.

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,

Royal Dutch Shell, engelsk,Amnesty International launched a major campaign in 2009 to highlight the massive oil pollution in the Niger delta over 50 years. It claimed that Shell’s oil spills and environmental damage in the delta had deprived hundreds of thousands of people of the ability to grow food, drink clean water, and enjoy health and an acceptable standard of living.

Amnesty described this a violation of human rights, and alleged that freedom of speech was denied and local people who had protested against the oil industry were being persecuted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.no/aksjon/flere-aksjoner/nigeria-shell-rydd-opp.

(pic)

The caption from Amnesty International’s 2009 campaign reads: “The next time you curse Shell’s petrol prices, think of what the ordinary man and woman in Nigeria have to pay. Demand that Shell clears [this] up.”

A UN report in 2011 concluded that Shell had neglected crude spills in the Niger delta for many years and that oil pollution in Ogoniland had had terrible consequences for the environment and the lives of the people who lived there.

Although Shell acknowledged in the mid-1990s that the delta had partly been polluted by its operations, the group took a hard line in blaming local society, criminals and saboteurs for most of the contamination.

Under Nigerian law, Shell had no liability for compensation if damage was caused by sabotage. Although it and theft had been part of the problem in the delta, documentary evidence showed that old pipelines and worn-out equipment caused much of the oil leakage.

Royal Dutch/Shell agreed in 2010 to pay NOK 600 million to people whose livelihood had been destroyed by oil spills in the Niger delta. The background was two large leaks in 2008 caused by faults in an oil pipeline, which the group admitted were the result of poor maintenance.

A compromise settlement was reached, with Shell apologising for the leaks it had responsibility for but reiterating its claim that most spills in the area were down to extensive oil theft and illegal refining.

Clarity, simplicity, efficiency and responsibility

Despite a number of incidents, where Shell was not the only oil company involved in human-rights and environmental issues, a solid group and a world-renowned brand had been built up over almost a century. However, it emerged in January 2004 that the Shell group had been exaggerating its oil reserves over a number of years. They had to be reduced from 20 to 16 billion barrels.

At the same time, the group was forced to admit that – for the third year in a row – it had pumped up more crude than had been secured in the form of new reserves.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 9 January 2004 “Shells oljereserver minker”. http://www.dn.no/nyheter/2004/01/09/shells-oljereserver-minker. The group had to undertake further writedowns in March and April. Internal documents revealed that top management had been warned as early as 2002 that booked reserves were overstated.

This was viewed in the USA as such a serious case of misleading market information that the Department of Justice wanted to launch a criminal investigation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 19 October 2011, “Vil verden ha olje nok i framtiden?”

Sir Philip Watts, chair of the board, and Walter van de Vijver, CEO of Shell Exploration and Production, were forced to resign with immediate effect in March 2004.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Olsen, Olav Søvik (2007). Rapportering og revisjon av olje- og gassreserver med utgangspunkt i Shell-skandalen 2004. Unpublished MSc thesis, Norwegian School of Economics.

(pic)

When the scandal erupted, Sir Philip Watts said that he had considered resigning but decided to stay on. Nevertheless, the announcement many had expected came soon afterwards. Sir Philip and Walter van de Vijver had to resign with immediate effect.

The Shell group was a huge undertaking. Parent companies Royal Dutch and Shell Transport were listed on the stock exchange from 2005, with 60 and 40 per cent respectively of Royal Dutch/Shell.

They owned a number of holding, service and operational companies involved in various sectors of the oil, natural gas, chemicals, coal, metals and other businesses in many countries.

As outlined above, the group was one of the most decentralised enterprises in the global oil industry. The management of each subsidiary was fully responsible for its own activities. This bureaucratic structure was ripe for reform. The old system meant slower decisions, confusing accounts and lack of transparency. Investors blamed the corporate structure for the failure to identify and deal with the oil reserves scandal.

The latter prompted a review of the group and its management, which led in November 2004 to the announcement that Shell was to create a new parent company with its head office in the Hague and its business offices in London.

This restructuring was completed on 20 July 2005. Royal Dutch Shell plc, as the new enterprise was known, had a single board, chair and CEO.

Shares in the company were split 60/40 between Royal Dutch and Shell shareholders respectively, in line with the original proportions decided in 1907.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/2fbca8ce-2948-11d9-836c-00000e2511c8.html?ft_site=falcon&desktop=true#axzz4VYorwEWv.

Jeroen van der Veer was appointed the first CEO of the merged company, and maintained that the new structure would create greater responsibility and a guarantee against audit problems.

It would also be more execution-oriented and competitive as well as less complex, he affirmed, and said that the fixed goal was to make Shell a different company. It would now concentrate on clarity, simplicity, efficiency and responsibility. The group has had its ups and downs, and has been exposed to scandals and boycott. But it remains one of the world’s largest enterprises, with 93 000 employees in more than 70 countries.

And the stylistically clean red-and-yellow shell which forms its logo is one of the best-known brands on the planet – so well established that the group decided in 1999 that the company name no longer needed to be part of it.

royal dutch shell, engelsk,

royal dutch shell, engelsk,