Political management of Norway’s oil sector

Tempo commission

The government appointed a commission of inquiry on 5 March 1982 to assess the future scope of petroleum operations on the NCS.[1] This became known as the “tempo commission”.[2] Chaired by Hermod Skånland, deputy governor of Norges Bank, it was to report to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE).

When explaining the appointment of the commission, the government pointed to the political consensus on maintaining a moderate pace of production on the NCS.

Such a pace had been “defined” in 1974 as 50-90 million tonnes of oil equivalent (toe) or 375-675 million barrels (boe) per annum. That corresponded to an average daily output of 1-1.85 million boe.

The higher figure had been proposed by the Labour government’s finance minister, while the lower was backed by the Storting opposition.

A White Paper from the finance ministry in 1974 calculated that annual output in 1981-82 would be 670 million barrels and would then decline from known fields.[3] (It might be noted in passing that peak output from the NCS, achieved in 2004, was 1 662 million toe.[4])

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk,

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk,In 1982, the workforce in the petroleum sector as such accounted for a mere 0.5 per cent of overall Norwegian employment and just one-fortieth of all industrial jobs.

But people were concerned that even limited changes in oil activity would have a substantial impact on other parts of the national economy.

During the 1970s, the petroleum sector had given an important stimulus to elements of Norwegian industry at a time when international economic development was weak.

It was seen that this had led to the acquisition of expertise which could lay the basis for new production and exports. But worries were nevertheless expressed that oil operations could divert key personnel from other industries.

An important element in the tempo commission’s mandate was an emphasis (as in the 1974 White Paper cited above) that the resources on the NCS had to benefit the whole society.

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, illustrasjon, graf, engelsk,

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, illustrasjon, graf, engelsk,At the same time, government oil policy should be shaped to ensure that associated social changes occurred within an acceptable framework.

The commission proposed that the government should use total demand from the petroleum sector as the criterion for managing, preserving and developing expertise in this industry and in Norway’s offshore supplies business.

Maximum and minimum levels should be set for this criterion. The base line was seen as particularly important in preventing Norwegian industry becoming overly dependent on a single sector.

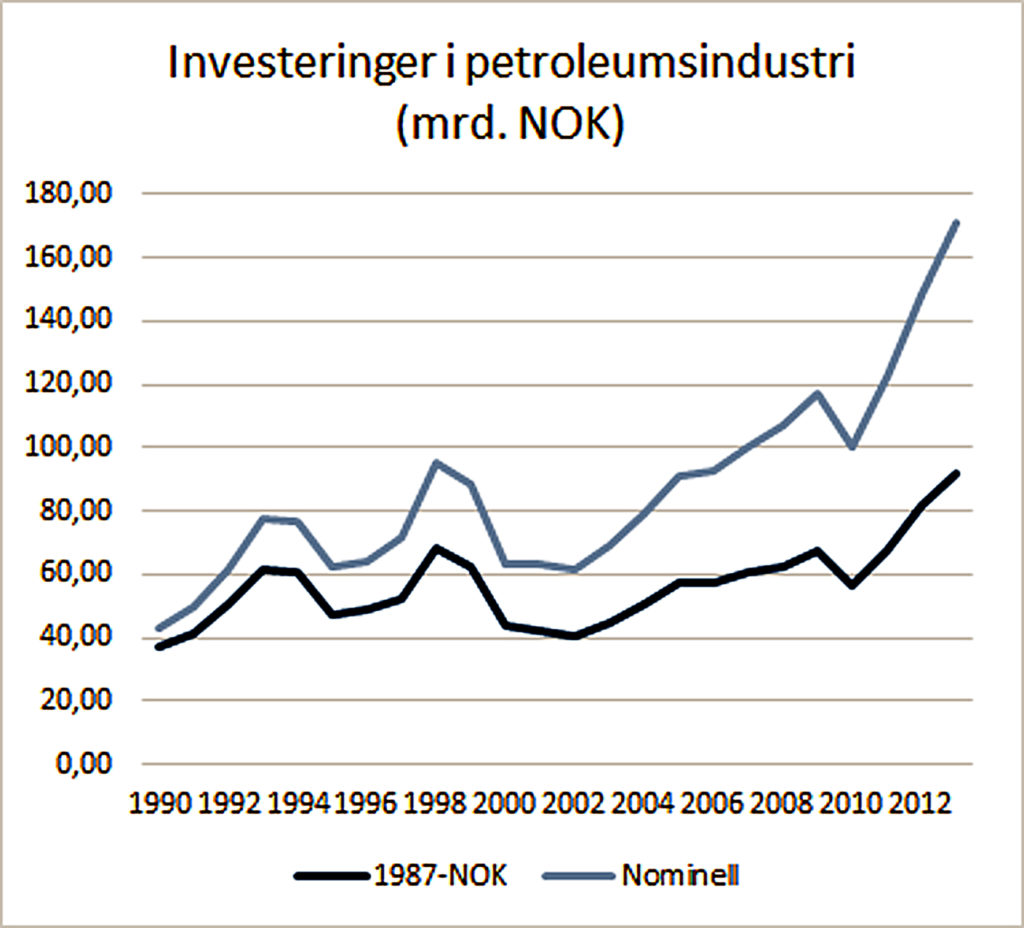

A stable level of investment of about NOK 25 billion per annum was considered to provide the desired effect. But it proved impossible to stick to that target.

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk, illustrasjon,

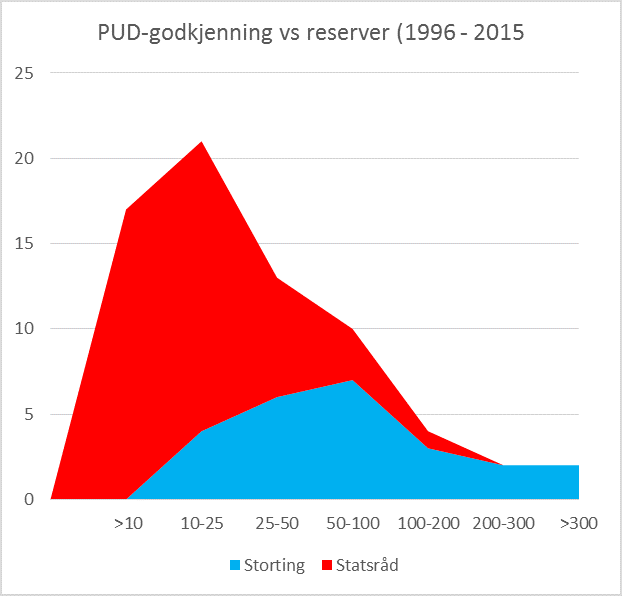

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk, illustrasjon,To achieve good management of activities, the commission called for a change to the practice of considering and approving all plans for development and operation (PDOs) of petroleum fields in the Storting’s spring session.

Instead, it proposed a process which would make it easier to even out the level of investment. This involved authorising the MPE to approve developments within a defined level of activity.

It was not until 1994 that a PDO was approved on these terms (for Vigdis on 19 December). Since then, about two-thirds of the 70 PDOs submitted up to 2015 have been ministry-approved.

A third proposal from the commission which has been highly significant and has attracted much attention was the creation of a special government fund.

This could serve as a buffer against big fluctuations in oil and gas revenues (from major price changes, for example). The suggestion was slipped in by interpreting the mandate a little broadly.

The “oil fund” – officially the Government Pension Fund – was not established until 1990, and the first transfer of revenues to it occurred six years later.[5]

Renamed the Government Pension Fund – Global in 2006, this sovereign wealth fund exceeded NOK 7 billion for the first time in 2015.

Queue

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk,

Offentlig styring av oljevirksomheten, engelsk,When oil prices were at their lowest following the dramatic slump in 1986, the government had sought to encourage companies to maintain their level of exploration activity through tax cuts.[6]

However, concern was expressed when presenting the national planning budget for 1988 that the pace of development on the NCS was too rapid.

The petroleum White Paper presented in April 1987 had stated:

A level investment of NOK 25 billion in 1987 value could be too high when viewed in relation to the desired development of the rest of the Norwegian economy. The government will therefore continue its work on the question of how high the level of investment in the petroleum sector should be. Further details on this will be provided in the national planning budget for 1988.[7]

The government sought to pursue a strategy which it believed would take account of developments in Norway’s mainland (ie, non-oil) economy, petroleum-related industry, the resource position and revenue risk.

Known as the “queue system”, this approach was meant to be based on operator plans adjusted for restrictions on gas sales. That would allow the government to decide on postponements to bring annual investment down to NOK 25 billion.

At that time, in the autumn of 1987, the MPE had received PDOs for the Snorre and Draugen fields and was awaiting them for Oseberg phase 2, Heidrun and Brage.

In addition, a plan for installation and operation (PIO) of the Haltenpipe gas transport system in the Norwegian Sea was due before Christmas.

The first chapter of the White Paper concluded that: “The government will revert to the question of which fields should be developed first.”

Significance for Draugen

This field lies in block 6407/9 in the Norwegian Sea, where a production licence was awarded on 9 March 1984 as part of the eighth licensing round. Oil was proven there in the same year.

Draugen was accordingly found right in the critical period of low crude prices. And the government had been advised to manage the pace of oil development by regulating investment.

To secure permission to develop the field, it was therefore important to be able to come up with a “low-cost” and efficient solution.

The size of field and the government’s talk of offshore tax reliefs also meant it was interesting to plan for a rapid development process.

Where a find the size of Draugen is concerned, it has historically taken about seven years on average from discovery to PDO approval by the Storting.

In Draugen’s case, however, the time lag was a mere four years.[8] Its PDO had been submitted in September 1987, a full year before it gained the green light.

Einar Knudsen, former head of communication at Norske Shell, recalls the process as follows:

The queue proposal was launched, in other words, while the authorities were right the middle of considering the PDO. Shell and its partners reacted sharply to this arrangement, which struck more or less like a bolt from the blue. We were wholly unable to accept this for a project which was profitable, risk-free and not least friendly to outlying districts. Our strongest ‘competitor’ in this respect was the Heidrun early production project.

We worked intensively with the Storting’s standing committee on energy and the environment, and also succeeded in building strong alliances with politicians from Møre og Romsdal [county] in general and Kristiansund in particular, since we envisaged operating Draugen from the latter. This was also documented via the impact assessment, which we used for all it was worth. The combination of strong project economics (not least for the government) and sustainable regional policy meant that we won the day and were not included in any queue system.[9]

With the exception of a small delay to the Brage development, the queue system was never actually put into practice. Investment admittedly remained at about NOK 25 billion for a couple of years, but already exceeded NOK 50 billion in 1987 value by 1992. See the figure.

In chapter 5 of the 1994 oil White Paper, which covered further development of the petroleum industry, the Ministry of Industry and Energy stated:

The level of activity on the Norwegian continental shelf has been managed largely through the award of production licenses in […] 14 licensing rounds. Managing activity through licensing policy also represents the best way to take care of the need to secure continuity and predictability in the activity. Direct intervention […] to influence activity could reduce efficiency and increase costs […]. Viewed in isolation, that could also weaken interest in investing on the Norwegian continental shelf.”[10]

When summarising this chapter, the White Paper concluded that the pace of development on the NCS was dependent on conditions outside the government’s control.

When the PDO for Draugen came to be approved by the Storting in the autumn of 1988, the MPE recommended that the proposed plateau rate of production be increased from 90 000 barrels of oil per day (bod) to 110 000.

This move would have a substantial negative significance for the private companies in the licence, given that the government operated at the time with a “sliding scale” for state holdings.

Under that system, the government would regulate the division of interests in a field to give the state a bigger share if daily plateau output forecast for it exceeded 100 000 bod.

Where Draugen was concerned, this would mean an increase in the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI) from 50 to 65 per cent – with a possible rise to 75 per cent.[11]

The corollary was that Shell’s interest would decline from 29.4 to 15 per cent. That would represent virtually a halving of its holding.

A decision to exercise the sliding scale did not have retroactive effect, so that all the expenses met by the companies until then would remain theirs while their future revenues were significantly reduced.

The licensees, with Shell in the lead, reacted sharply to this recommendation and initiated effective lobbying efforts. These proved a success, and the PDO was approved with 90 000 bod as the expected plateau production.

Three alternatives for developing Draugen were referenced in the 1988 budget recommendation. When the PDO was approved on 19 December that year, interests in the licence were revised so that the SDFI and state oil company Statoil obtained a combined holding of 65 per cent.

Shell had to accept a reduction in its share to 21 per cent. And a further eight per cent increase in the state interest was approved by the Storting on 1 July 1995.[12]

Interests in the licence were again changed several times after the standing committee on energy and the environment recommended this increase from 65 to 73 per cent.

Over the years until 2002, however, the state’s direct holding was reduced to 47.88 per cent – which is where it stood in 2017.

[1] Norwegian Official Reports (NOU) 1983: 27, Petroleumsvirksomhetens framtid.

[2] Ryggvik, Helge and Smith-Solbakken, Marie (1997), Norsk Oljehistorie volume 3: 410.

[3] Ministry of Finance, Report no 25 (1973-74) to the Storting.

[4] Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (2013). Facts. The Norwegian Petroleum Sector.

[5] Norges Bank Investment Management www.nbim.no/no/fondet/historien/.

[6] Ryggvik, Helge and Smith-Solbakken, Marie (1997), Norsk Oljehistorie volume 3: 413.

[7] Ministry of Petroleum and Energy: Report no 46 (1986-87) to the Storting.

[8] Norwegian Petroleum Museum http://www.kulturminne-valhall.no/Feltet/Geologi-og-reservoar/Fra-null-til-hundre-i-loepet-av-20-aar.

[9] E-mail from Einar Knudsen, former head of communication at A/S Norske Shell, to the Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 2016.

[10] Ministry of Industry and Energy, Report no 26 (1993-94) to the Storting: 53

[11] Energy and industry committee: Budget recommendation no 8 to the Storting. Supplement 2. (1988-89).

[12] Energy and environment committee: Budget recommendation no 197 to the Storting. (1994-1995).

The heliport at KvernbergetStavanger’s leaning tower