ROV work inside the platform

All the hatches at the bottom of the Condeep concrete gravity base (GBS) structure were to be opened with the aid of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs).

The lower part of the GBS had been cast at Hinnavågen in Stavanger, while slipforming of the tall monotower shaft took place in the deep fjord at Vats further north.

Subsea Dolphin was involved as early as the latter stage. Arild Jenssen, one of the company’s ROV pilots, remembers this phase well.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Arild Jenssen in conversation with Kristin Øye Gjerde, 31 March 2016.

These devices were used inside the GBS because the shaft was filled with seawater once the platform had been installed on the field, and they could therefore move around as required.

Preparing for internal ROV work while readying the platform for tow-out proved a special experience because of the motion in the shaft, which was several hundred metres tall.

That meant the tubing which ran from the base of the structure through holes in the intermediate decks banged against the sides of these apertures. This in turn generated vibrations and a “bong, bong” sound almost like church bells.

The ROV pilots wanted to insert wooden wedges in the holes to prevent the slamming, but the engineers from builder Norwegian Contractors maintained that this motion was as it should be.

“We Subsea Dolphin operators were on board during the towout [in 1993],” recalls Jenssen. “It was a fantastic experience. The view was great while deballasting the platform in calm and beautiful weather.”

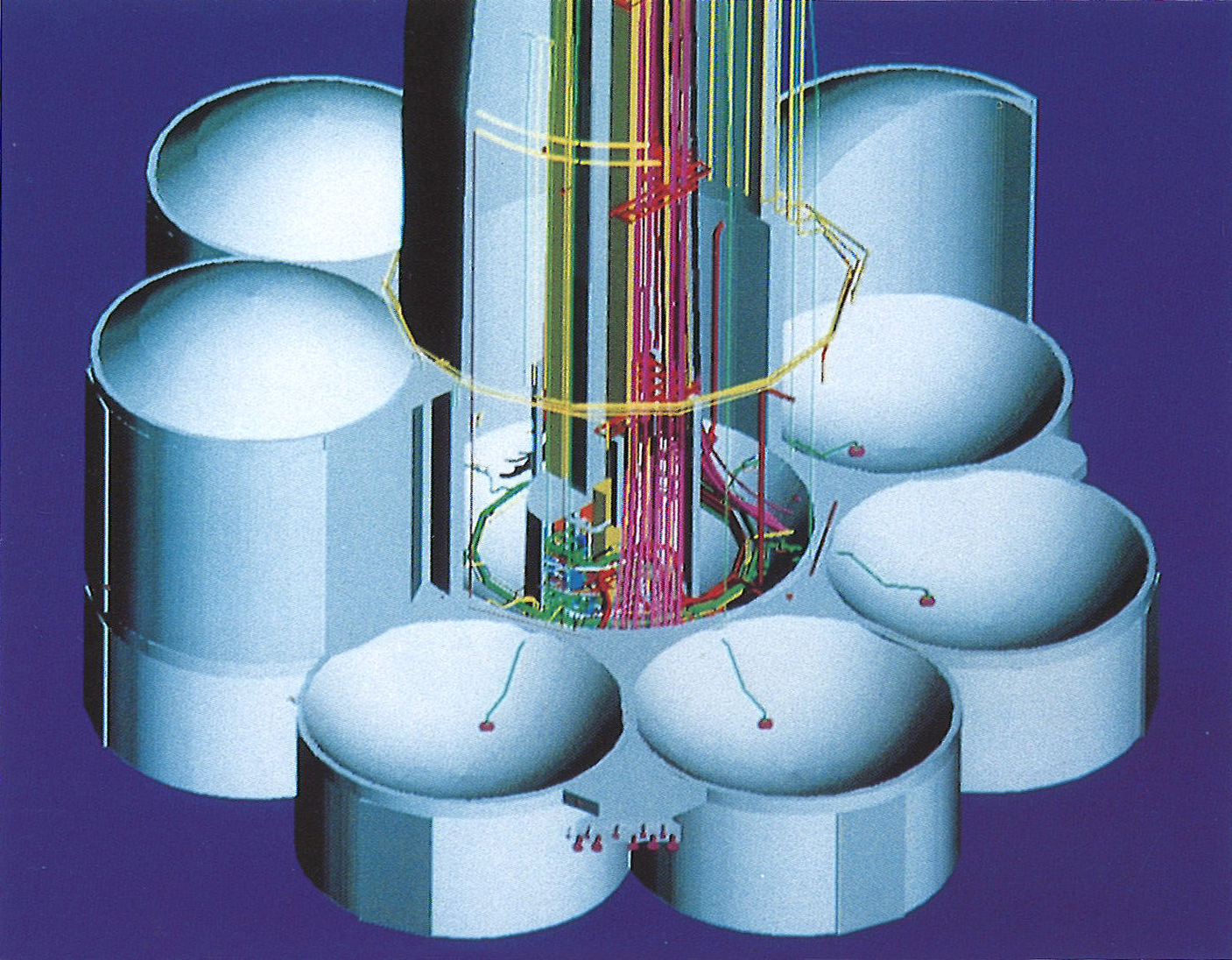

Like the other Condeep concrete platforms, the Draugen GBS had cylindrical storage tanks clustered around the central shaft. The latter contained about 70 metres of water during towout, while a big tank also held ballast water.

A concrete pipe with a square cross-section ran down the centre of the shaft to a “mini-cell” at the base of the platform. This extended upwards from a depth of 250 metres to 180 metres.

The mini-cell contained piping positioned beneath the other storage cells for pumping out grout in order to fill the spaces beneath the GBS and stabilise the ground.

Installed in 250 metres of water, the platform ended up 0.3 degrees out of true – which added up to a horizontal offset of 1.5 metres at the topside height of 300 metres.

Although this was a very small deviation, it was enough to create a few problems for guiding the ROVs through the narrow aperture in the various intermediate decks.

Another issue was that the platform started to sway once it was finally in place. It had been known that skyscrapers could oscillate many metres in strong winds, and the Draugen structure was expected to behave similarly in response to wind and waves.

But this platform was the first design of its kind, with only a single shaft, and the swaying created a good deal of concern among control room staff.

“A plumb line hung from the ceiling there, and moved in big figures of eight,” Jenssen relates. Since it made people nervous and had no practical significance, the plumb was eventually removed and the workforce became used to the motion.

Drawing of Storage tanks and pipes inside draugen.

Drawing of Storage tanks and pipes inside draugen.The ROV pilots had to familiarise themselves with the GBS design before the shaft was water-filled, so that they would be able to guide their vehicles down at the bottom.

To reach the base of the structure, they first had to take a lift through the narrowest section of the shaft to the deck where the mini-cell started.

They then transferred to a lift inside the mini-cell itself to the bottom of the shaft, where they could see the pipes which extended beyond the concrete wall. “To seawater”, the sign read.

Hatches in the shaft were to be opened with the aid of ROVs once the space was water-filled in order to pull in the conductor tubing.

These in turn were where flowlines with oil and gas, umbilicals and control lines would enter the platform before passing up the shaft to the topsides.

Work could start as soon as the mini-cell was filled with water. Two ROVs were used in the shaft – a Sprint observation model with cameras and a big Scorpio with manipulator arms.

But the problems posed by the 0.3-degree slant now manifested themselves, since the Scorpio could no longer be easily lowered as intended through the square holes in the various shaft decks.

The machine suffered considerably from the buffeting it got on the way up and down because it was difficult to hit the openings exactly.

In the lowest spaces, which were water-filled, the pilot had to use the propellers to manoeuvre the ROV into position to pass through the holes.

If things went really badly, the umbilical could be damaged and the machine would shut down. The only option then was to haul on the cable to get the ROV out.

A big framework containing cylinders and cabling meant the lifting point on the Scorpio could be moved to the best possible position before and after dives.

It was not easy to work With a Scorpio inside Draugen.

It was not easy to work With a Scorpio inside Draugen.The pilot sat safe and dry high up in a container on a topside deck and controlled the ROVs as they removed the temporary hatches used to seal the platform during construction and towout.

But the work was demanding. The machines had to be manoeuvred through a jungle of pipes, bracings, cables and decks in very poor visibility.

The pilots usually “flew” with the aid of sonar images as they hunted for the hatches to be removed. In many cases, the space available was only just enough for the ROV to work.

Flexible risers connected the platform to the subsea installations, and entered the GBS through J tubes which opened at the seabed. Pulling the risers into these tubes was accomplished using a wire lowered down the shaft with the aid of the ROVs.

Once everything had been hooked up, the contract for subsea work during the production phase was awarded to Stolt Comex Seaway and its machines replaced the Subsea Dolphin ROVs.

The ROV’s had to do a lot of work inside Draugen.

The ROV’s had to do a lot of work inside Draugen.They conducted annual inspection and maintenance work. And several years of repair work were required inside the shaft after cracks had been found in the GBS base around the conductors.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Arild Jenssen in conversation with Kristin Øye Gjerde, 16 April 2016.