Draugen gas – flaring or reinjection

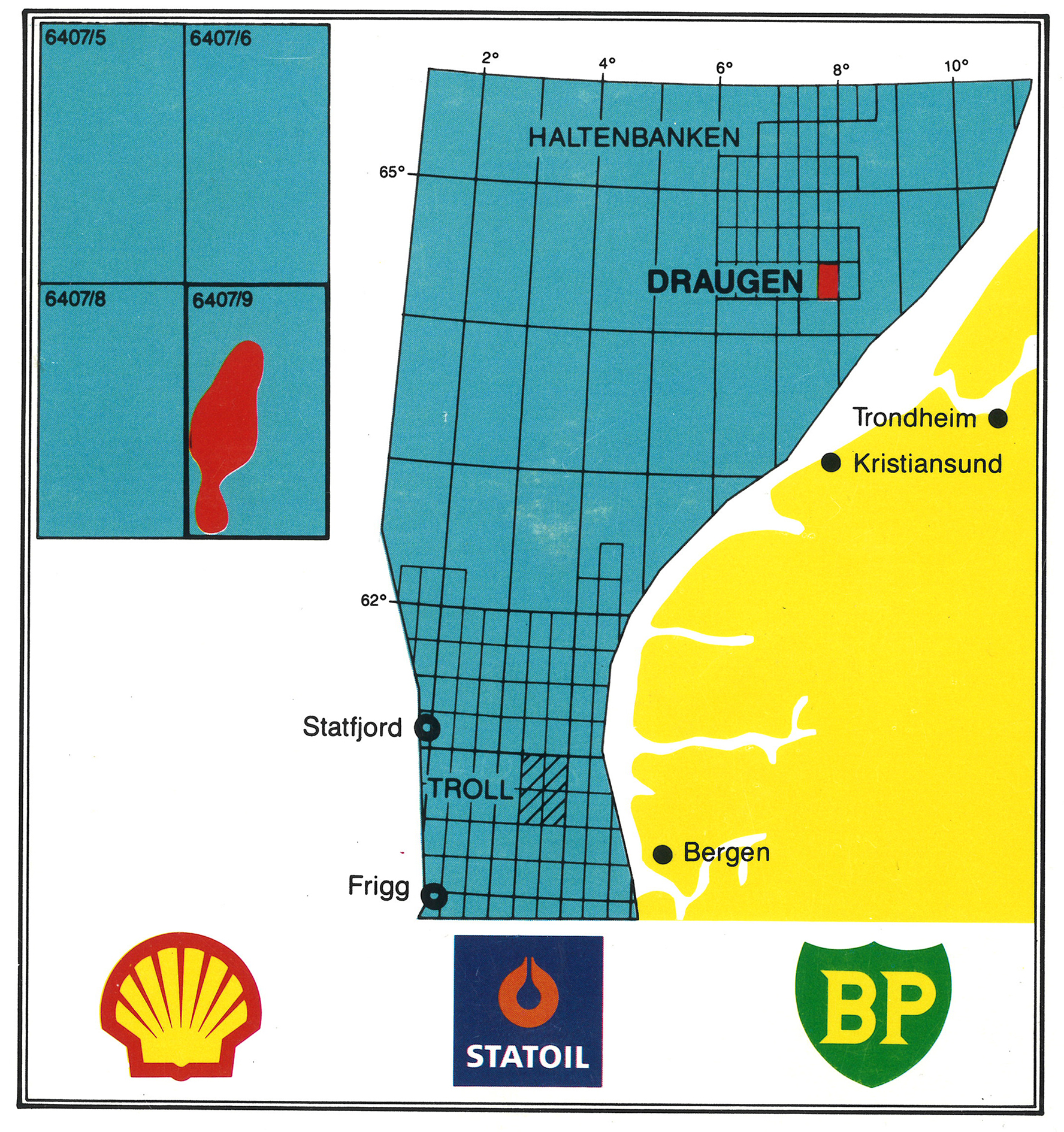

- Norske Shell was operator for this groundbreaking project in block 6407/9.

- This acreage was covered by production licence 093, awarded in 1984 as part of the eighth licensing round.

- Norske Shell owned 30 percent, Statoil 50 percent and BP 20 percent.

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, illustrasjon, kart, engelsk

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, illustrasjon, kart, engelskThat part of the Norwegian Sea where Draugen was discovered has a distinctive geology. In the exploration phase, a lot of geologists thought no hydrocarbons had formed there but could have migrated from areas of the Halten Bank where discoveries were already made.

Strata of interest lay at shallow depths in the sub-surface. Attention was concentrated on an area where seismic surveys showed signs of a heightening.

These assumptions proved correct, and Draugen was found in a reservoir rock with good production properties. It was primarily an oil field, but with small quantities of associated gas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B., & Norske Shell. (2012). Energi til å bygge et land : Norske Shell gjennom 100 år. Tananger: A/S Norske Shell.: 173–74.

Oil could be shipped from the field by shuttle tankers, but the question was how the gas should be dealt with in an area entirely without pipeline infrastructure.

This question will be addressed in more detail in this article.

Collective Halten Bank solution?

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, illustrasjon, kart, engelsk

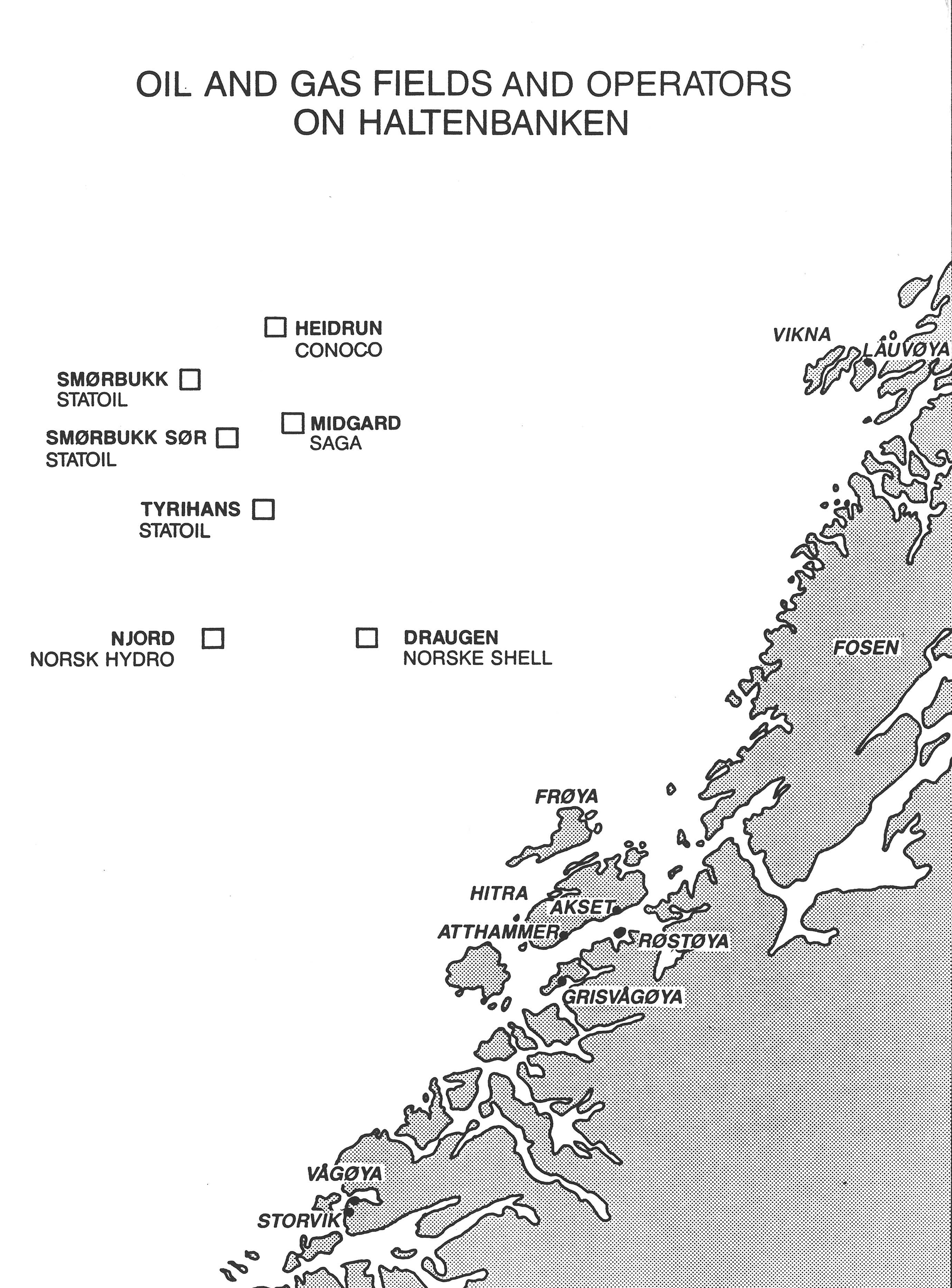

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, illustrasjon, kart, engelskA study of transport solutions for oil and gas from the Halten Bank area of the Norwegian Sea was initiated in 1985. Draugen was assessed for development at the same time as Heidrun, operated by Conoco.

The Halten Bank had a number of proven gas resources – Midgard, Tyrihans, Smørbukk, Smørbukk South and Njord – and more were possible. So the basis existed for a degree of coordination.

In a letter of 24 February 1987, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) asked the five operators in the area to produce a joint study of the landing issue. This was presented in September.

Offshore loading was recommended by Statoil, Saga Petroleum, Conoco and Shell as the most favourable solution in financial terms for oil.

Based on its own studies of the opportunities for such a solution, Norsk Hydro recommended pipeline transport of crude oil to a terminal on land.

Where gas was concerned, the companies would eventually have to come up with a landing solution for the Halten Bank. But it was uncertain when this might happen and what the choice would be.

Shell and the MPE had several discussions in 1988 on how to deal with the associated gas in Draugen.

The ministry wanted to order the licensees to find a long-term solution based on a gas-gathering system for a number of Halten Bank fields, including Heidrun. Each company’s investment should be proportional to the capacity required.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter of 14 December 1988 from the MPE to the standing committee on energy and industry of the Storting (parliament).

Another issue was how the gas would be used. Statoil, who had played a leading role in the work on developing the pipeline network on the NCS, led studies on the gas market and where a possible terminal should be located.

Statoil and the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) had already collaborated for a time on studying a possible gas-fired power station in mid-Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NTB, 6 March 1986, “Statoil og NVE vurderer gasskraftverk”.

If built, such a facility would rank as the biggest in Europe – and 30 times larger than the hydropower station at Alta in northern Norway, completed in 1987 after extensive protests.

It could have an annual capacity of 15 terawatt-hours (TWh). Both the Swedish and Finnish state power companies showed great interest in imports, and discussed this with the NVE management. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 27 November 1986, “Gasskraftverk planlegges i Midt-Norge”.

Where the gas should be landed was a key question. Five options were identified, spread between three counties: Nord-Trøndelag, Sør-Trøndelag and Møre og Romsdal.

How much gas would be landed was still unclear, so three of possibilities were investigated – including a minimum option involving 0.7 TWh of electricity capacity for local consumption.

The others were a large 2.5 TWh gas-fired power station with exports to Sweden, and a maximum option which included gas exports to potential markets as well as electricity generation.

These solutions were based on one, 3.5 and eight billion cubic metres of gas per year respectively. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Norske Shell AS, Draugen – konsekvensutredning, 1987: 56.

Storting proposition (Bill) no 56 (1987-88), based in part on this study, assumed a gas pipeline from Heidrun and Draugen with an annual transport capacity of one to 1.5 billion cubic metres.

Running to a land terminal and feeding a gas-fired power station, this option was costed at NOK 2.5 billion. One billion cubic metres of gas per annum could lay the basis for 4.5 TWh.

Another solution was to use the gas as feedstock and energy for industrial production. In the longer term, selling gas to Sweden through a pipeline via eastern Norway was one option.

Sales of gas-based electricity to Finland/Sweden offered an alternative, while a tie-in to existing pipelines in the North Sea and sales of liquefied natural gas were also discussed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proposition no 56 (1987–88) Innfasing av feltutbygginger i årene fremover. Utbygging og ilandføring av olje og gass fra Snorrefeltet. Item 17.

Norway’s gas negotiating committee (GFU), comprising domestic oil companies Statoil, Hydro and Saga, held talks in 1989 with the Swedish authorities on gas deliveries from the Halten Bank.

These negotiations concerned 2.5 billion cubic metres of gas per annum from 1995. However, the Swedes set demands which were difficult for the GFU to concede.

They wanted at least one of the fields supplying their gas to be below the 62nd parallel. But the relatively modest volumes involved from the mid-1990s made pipelines from both the Halten Bank and the North Sea uneconomic, so the talks failed.

Sweden’s demand reflected the fact that deliveries from the Halten Bank alone would provide insufficient security of supply – particularly for power stations intended to use part of the gas.

The Swedes took the view that delivery regularity would be much better from the North Sea. Halten Bank gas via a land terminal to the Gothenburg area would be too vulnerable when maintenance was required, and shutdowns might occur at several of the hubs along the way.

Developments based on subsea solutions did not reduce the risk. The Swedes felt the North Sea had more fields and delivery options. They turned their attention instead to alternative deliveries both from the Soviet Union and from or via Denmark. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 14 October 1989, “Svenskene vil ikke ha Haltenbanken”.

From flaring to reinjection

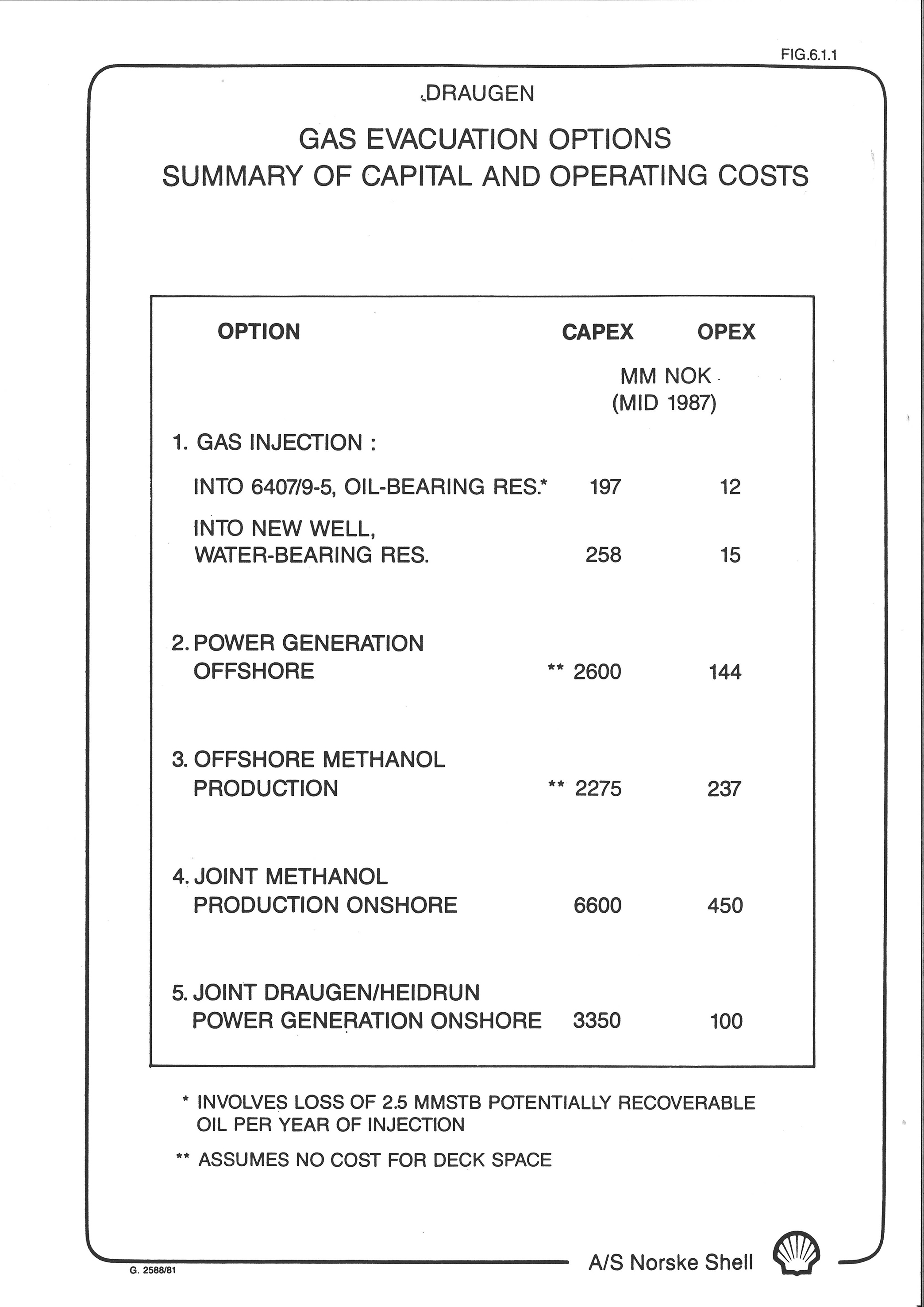

Shell’s original plan for Draugen involved controlled gas flaring during the initial production years. That was clearly stated in the plan for development and operation (PDO) submitted to the government on 22 September 1987.

The company noted that associated gas from the field could be landed through a gas-gathering pipeline and used for electricity generation.

However, it would be a long time before the necessary gas-fired power station was ready and the best and cheapest solution in the interim was flaring on the field.

The Draugen licensees had also conducted studies which showed that the gas could be injected in a separate formation, but this was regarded as too expensive.

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, avis, engelsk

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, avis, engelskA solution involving gas reinjection could moreover only be possible for about three years before having a negative impact on oil production.

The flaring proposal attracted criticism. Daily paper Bergens Tidende presented it under the headline “Energy corresponding to six Alta power stations to be burnt on Draugen”.

According to the accompanying story, “Key players in Norway’s oil community characterise … Shell’s plans for the Draugen field as pure madness, and propose that this development be postponed until the second half of the 1990s”.

The MPE was unsparing, and its comments about Shell in the Storting proposition were fairly cutting:

“Were the licensees at a later time to oppose participation in a gas transport system on terms which the government found it needed to set, production from Draugen could be halted by the authorities to avoid wastage of petroleum”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proposition no 1. Supplement no 2. Utbygging av Draugenfeltet og lokalisering av drifts- og basefunksjoner for feltene Draugen og Heidrun: 35.

Uncertainty over the choice of a gas solution for Draugen meant that the ministry wanted to postpone a development decision for up to a year. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proposition no 56 (1987-88) Innfasing av feltutbygginger i årene fremover. Utbygging og ilandføring av olje og gass fra Snorrefeltet. Item 17.

Shell was not happy with that. Delay was the last thing it wanted, and the company quickly revised its plans for flaring.

Bergens Tidende could now report: “Shell will be withdrawing its own proposal to base development of the Draugen field on flaring the gas. Instead, [it] will return the gas to the reservoir. In that way, the company hopes to move up the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate’s development queue”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, Energi til å bygge et land. Norske Shell gjennom 100 år, 2012: 176–77.

Gas flaring was no longer a relevant option in the 1988 recommendation from the Storting’s energy and industry committee on developing Draugen.

The committee emphasised that, even though the quantities of gas involved were relatively small, flaring them would not be permitted for environmental and resource management reasons.

Its recommendation assumed that, until the gas could be sent ashore through a pipeline from the Halten Bank, it would be injected in the Husmus aquifer about 10 kilometres from Draugen.

This process could continue for about three years, and calculations indicated that 75 per cent of the gas could be produced later.

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, engelsk

draugengass falking eller reinjisering, engelskMoreover, opportunities existed to extend gas injection for a further three years by utilising a neighbouring formation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Budget recommendation to the Storting no 8. Supplement no 2. (1988–89) Innstilling fra energi- og industrikomiteen om utbygging av Draugenfeltet og lokalisering av drifts- og basefunksjoner for feltene Draugen og Heidrun.