Opening the northern NCS

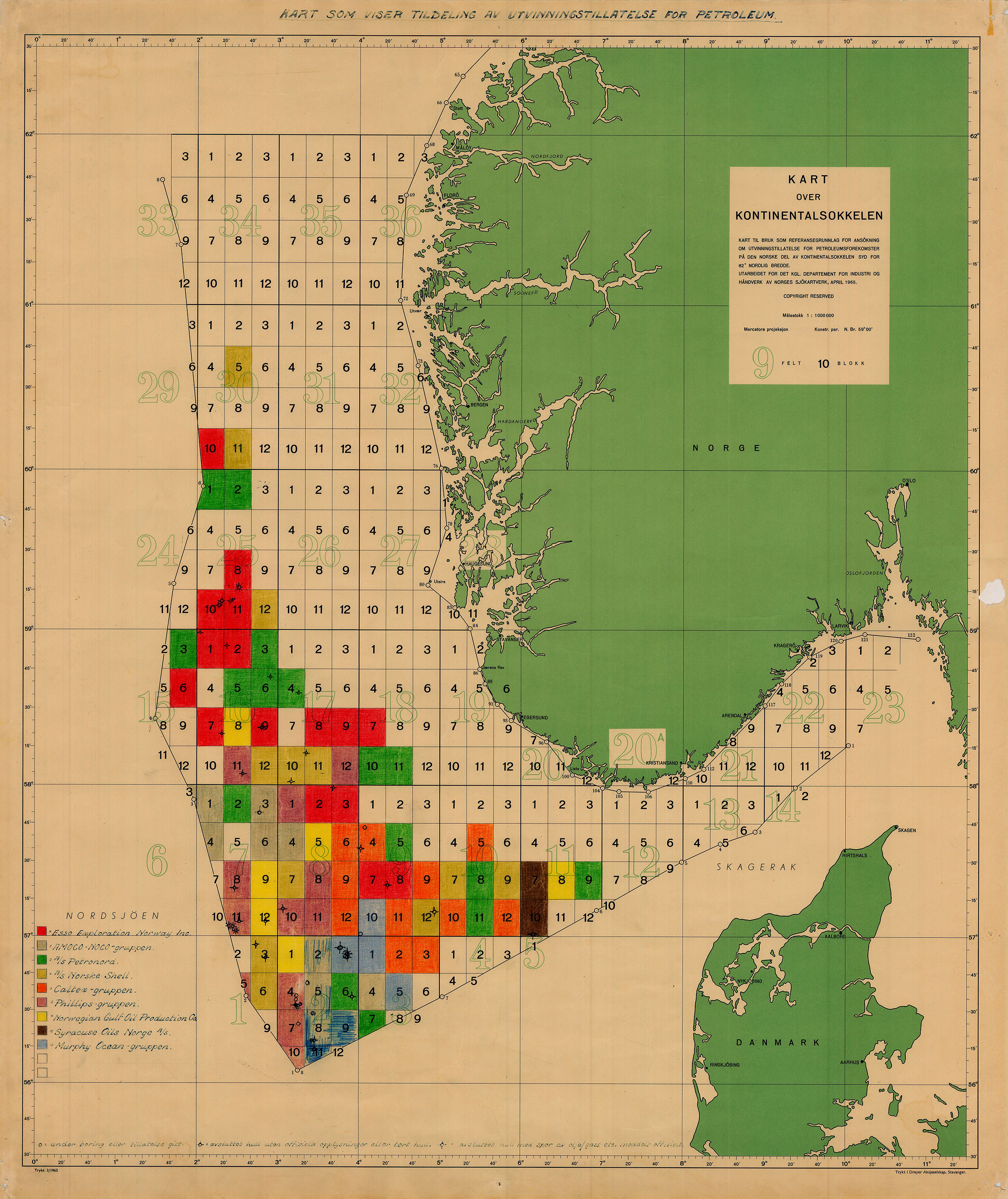

When oil operations were first permitted on the NCS in 1965, activity was confined to the North Sea. So the question is why it took 15 years before offshore activities moved further north.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

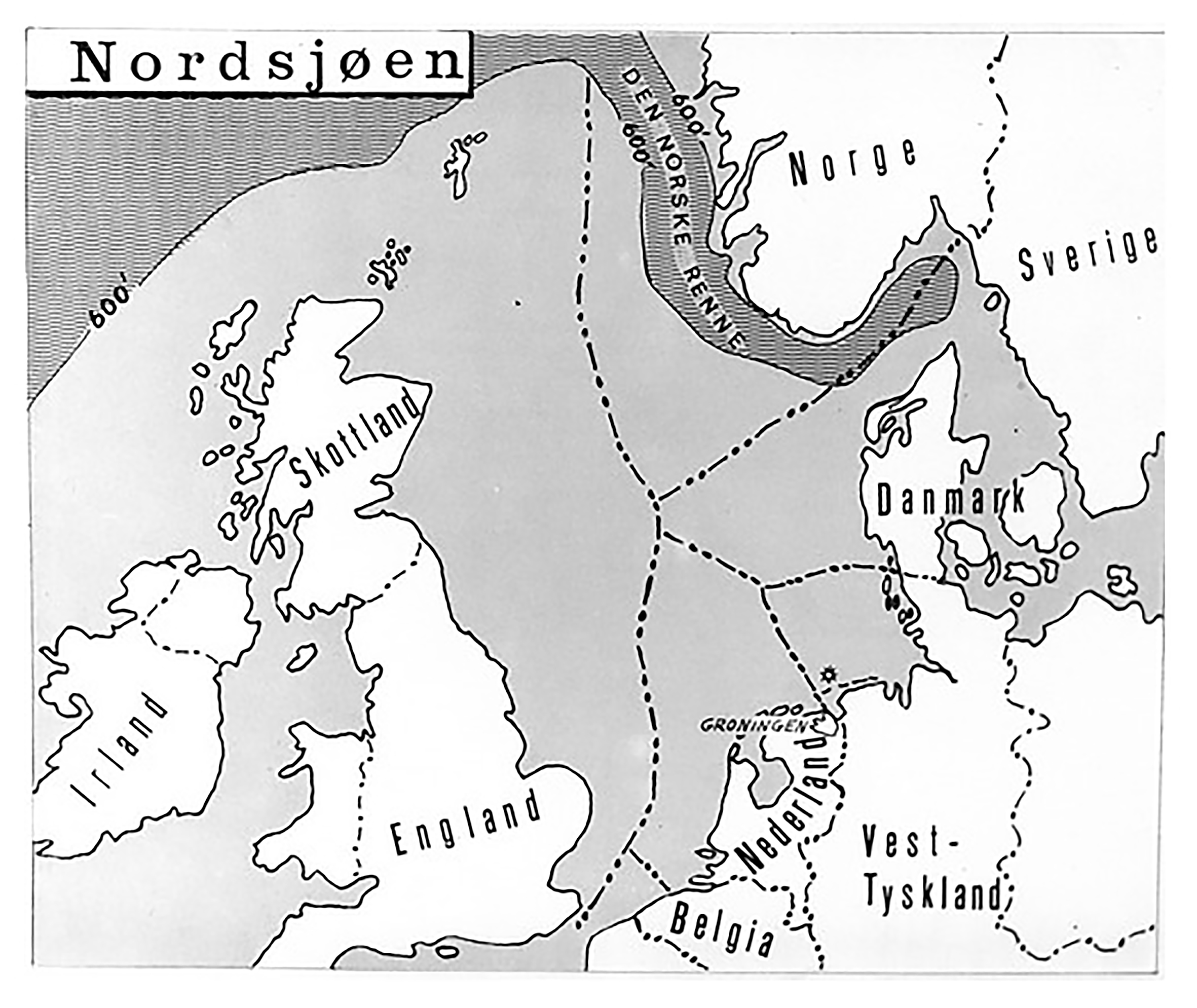

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskThe 62nd parallel itself does not represent a physical reality. When the boundary agreements for the North Sea were reached in the mid-1960s on the basis of the median line principle, this latitude – more precisely, 61°44’12”N – marked the northern limit of Norway’s dividing line with the UK.

Limits to Norwegian sovereignty were less obvious above that parallel, since international law at the time failed to provide clear rules about the outermost continental shelf boundary.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskThe Norwegian government stuck to the more general criterion in the Geneva convention on the continental shelf, which set the outer limit “where the depth of the superjacent waters admits of the exploitation of the natural resources of the said areas”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 294 to the Storting (parliament) (1970-1971) from the reinforced standing committee on industry. Exploration for and production of underwater natural resources on the NCS, etc.

Northern dream

Following the discovery of the Ekofisk field in the North Sea in 1969, the dream of also finding oil further north in the Norwegian and Barents Seas took hold.

Petroleum-related activity in the central and northern regions of Norway was put on the political agenda, although the intensity of the attention devoted to the subject varied.

So did the issues discussed in this context: environmental protection, oil spill prevention, fishing, base locations, jobs and regional development. So how did the debate develop, and who contributed?

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, stortingsmelding, industridepartementet, engelsk,

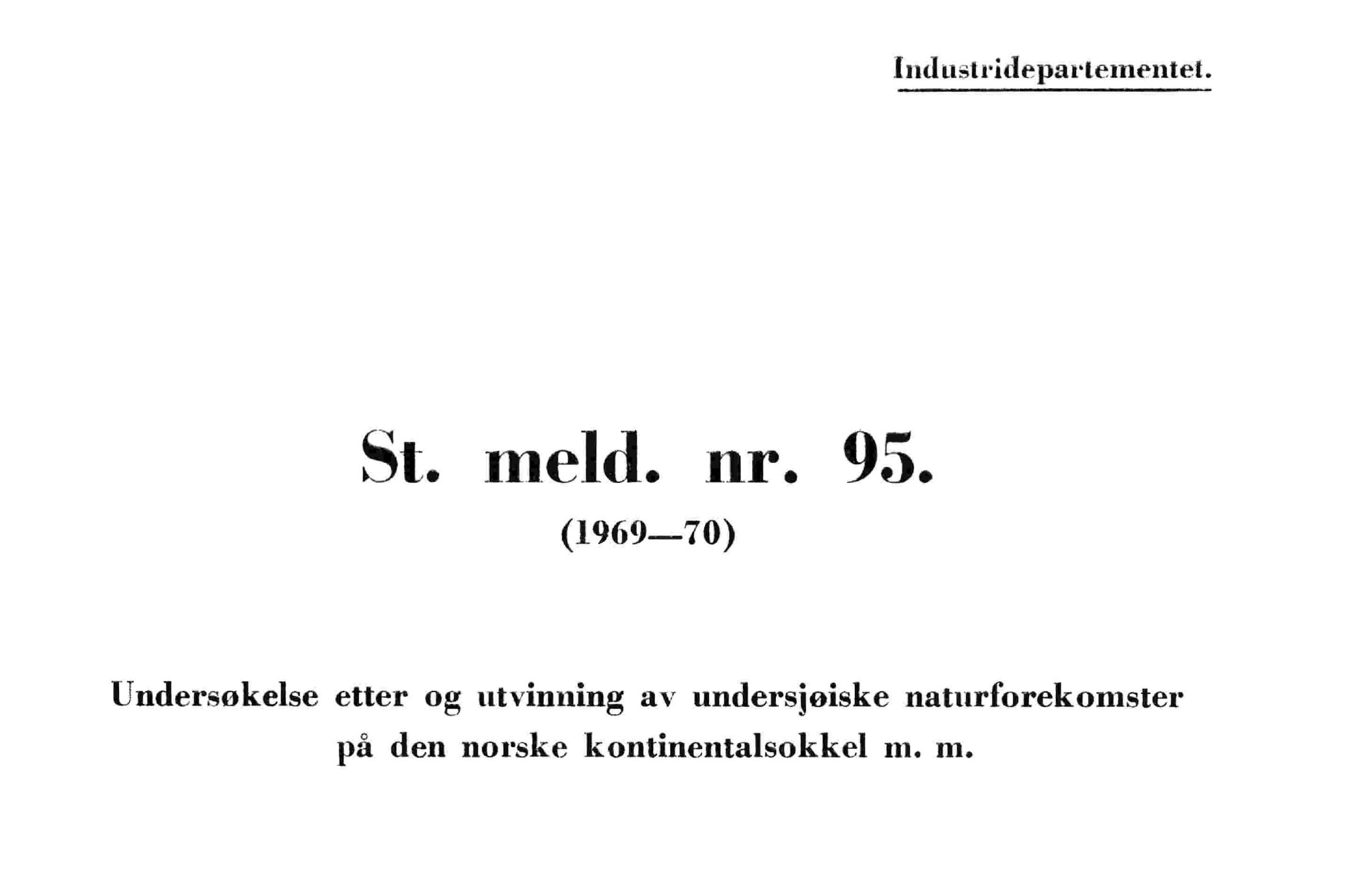

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, stortingsmelding, industridepartementet, engelsk,The question of what should be done with the rest of the NCS was first raised by the non-socialist coalition government headed by Per Borten in White Paper no 95 (1969-70). This argued that resources in the Norwegian and Barents Seas should be mapped.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 95 to the Storting (1969-1970). Exploration for and production of underwater natural resources on the NCS, etc: “With reference to the interest shown and the need to maintain continuous activity on the continental shelf, the Ministry of Industry has concluded that the summer of 1971 could be a suitable time to commence exploration for petroleum north of the 62nd parallel.”

Opening this part of the NCS was supported by the foreign ministry, the Norwegian Petroleum Council and all Norwegian and foreign oil companies. The question was rather when exploration could begin there.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rommetvedt, Hilmar (2014). “Oljeleting nord for 62. breddegrad. Tilbakeblikk på en laaang beslutningsprosess.” Norsk Oljemuseums årbok: 47.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, stortingsmelding, industridepartementet, engelsk,

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, stortingsmelding, industridepartementet, engelsk,Nothing more came of this White Paper – the first in a long series. The Labour Party came to power under Trygve Bratteli in the spring of 1971, and returned to the question of petroleum operations above the 62nd parallel.

White Paper no 76 (1970-71) revealed no divergent views. The political parties were still largely in agreement. Environmental protection and nature conservation were mentioned, to be sure, but not included in the assessment.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 76 to the Storting (1970-71). Exploration for and production of underwater natural resources on the NCS, etc.

During the Storting’s consideration of this document, it was discussed by a reinforced standing committee on industry which submitted its recommendation in the spring of 1971. That included a reference to a statement from the council executive boards in Finnmark, Troms and Nordland (Norway’s three northernmost counties).

They called for the northern NCS to be opened as soon as possible because of the regional policy challenges facing them, which included economic decline and depopulation.

Broad agreement prevailed in the Storting that providing new industrial activity and countering emigration in this region represented a national political responsibility. That encompassed developing a north Norwegian petroleum – and preferably also petrochemical – industry.

In addition, the recommendation presented what became known as the “10 oil commandments”, a set of principles which laid the basis for the subsequent Norwegian oil model.

Extending activities northwards was addressed by the ninth “commandment”: “that a pattern of activities is selected north of the 62nd parallel which reflects the special socio-political conditions prevailing in this part of the country.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 294 to the Storting (1970-71) from the reinforced standing committee on industry. Exploration for and production of underwater natural resources on the NCS, etc: 636. This recommendation was based on reports no 95 (1969-70) and no 76 (1970-71) to the Storting.

The committee’s recommendation was approved unanimously.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting Proceedings, 14 June 1971. Item no 17. Recommendation no 294 to the Storting (1970-71) from the reinforced standing committee on industry. Exploration for and production of underwater natural resources on the NCS, etc (recommendation no 294 to the Storting, see reports no 95 (1969-70) and no 76 (1970-71)): 3240.

Nothing was said in the recommendation or the debate about the NCS off the counties of Møre og Romsdal, Sør-Trøndelag and Nord-Trøndelag (usually referred to as part of mid-Norway).

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskA minority centrist coalition led by Christian Democrat Lars Korvald took over when Bratteli resigned after European Community membership for Norway was rejected by a referendum in 1972. In its White Paper no 71 (1972-73), the new government undertook to “speed up work on exploring the NCS north of the 62nd parallel”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 71 to the Storting (1972-73). Long-term programme for 1974-77: 323. It anticipated that drilling could begin in 1974-77.

Bratteli returned to power in 1973. His administration now aimed to start exploration off northern Norway between 1975 and 1977.

So far so good. Four governments in a row had agreed on all significant points about oil policy in northern Norway. Their White Papers had been dominated by issues of governance and timing.

In other words, drilling for oil above the 62nd parallel was not regarded as a political question. It was rather viewed as a solution to a regional policy problem. Delays were due to technical issues, and “green” values had yet to find expression. Marine pollution had been touched on in the White Papers, which concluded that drilling above the 62nd parallel could be pursued with an “acceptable level of risk”.

No opposition to the prevailing oil policy existed in the Storting, and nobody was against petroleum operations on environmental grounds.

The environmental movement had not experienced its breakthrough in Norway at this time (see the article on Shell’s history), and the desire to move north was deeply entrenched in a wish to spread industry and jobs to local communities.

Polarisation and new participants

Political desires and decisions were not why the dream of oil operations on the northern NCS failed to materialise in the early 1970s, with the go-ahead constantly postponed.

One reason was oil-industry capacity problems. While the international companies wanted new exploration acreage, their primary interest lay in the more accessible North Sea.

A number of large discoveries were made there in the early 1970s, and the industry would have plenty of development projects for a long time to come. The civil service also needed to prepare for an expansion northwards.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge (16 October 2014). Striden om oljeboring i nord. Store norske leksikon. Downloaded 1 February 2017 from https://snl.no/Striden_om_oljeboring_i_Nord.

However, the consequence of these delays was that more participants secured both the time and the opportunity to enter the debate with various issues and solutions.

A new phase was initiated with White Paper no 25, presented by the Bratteli government in February 1974. This took the first systematic look at the place of petroleum in a broader social context.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sejerstad, Francis (1999). Systemvalg og politikk. Universitetsforlaget: 33.

Issues related to oil production on the northern NCS were discussed more explicitly and placed in a wider perspective. Topics now discussed were employment, restructuring problems, regional policy, and managing resources and the revenues they would generate.

Attention focused particularly on how to avoid the potentially damaging effects of excessive oil income on the Norwegian economy. A “moderate” pace of production was the solution proposed.

The White Paper stated that: “On the basis of a desire for long-term resource utilisation and after an overall social assessment, the government has … decided that Norway should maintain a moderate pace in recovering the petroleum resources”. Such an approach was also necessary in order to provide the time and opportunities required to implement the necessary social changes.

The debate on the pace of production created a broader basis than discussions about drilling above the 62nd parallel, even though many of the same arguments were repeated.

Production must not be allowed to outstrip the parallel development of technology and emergency preparedness, so that the industry could stay within an “acceptable” level of risk.

While environmental protection and possible threats to fishing were also drawn into the discussion, these issues did not acquire decisive significance. “With a moderate pace of petroleum operations, environmental problems will not exceed a level the government believes could be handled in a satisfactory way,” the White Paper observed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 25 to the Storting (1973-74). The role of petroleum in Norwegian society: 16.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

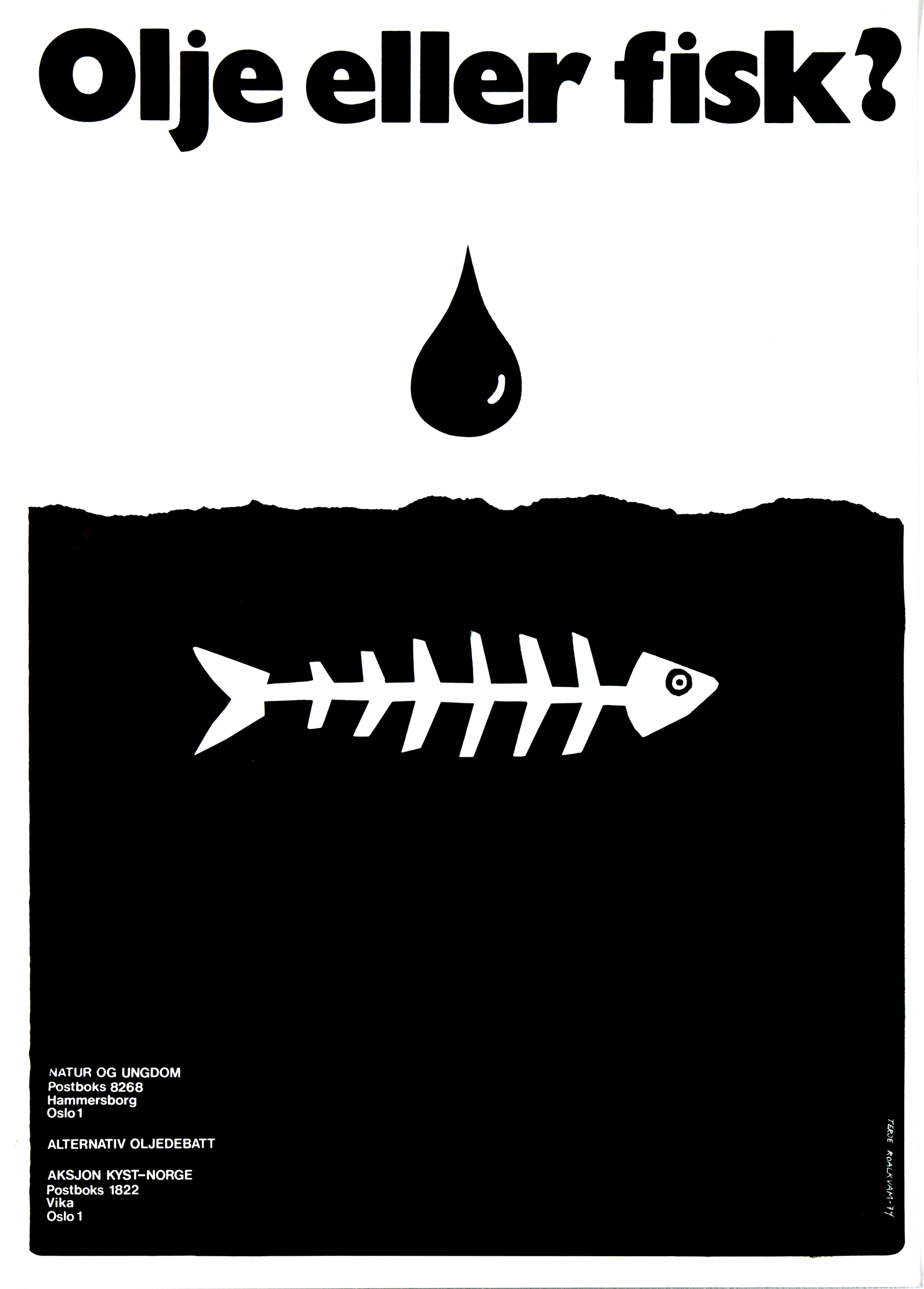

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskNorway’s petroleum policy debate in the second half of the 1970s focused strongly on opening the northern NCS and when this should happen.

Divisions became clearer – oil or fish, oil or the environment. A gradual shift occurred from a concentration on opportunities and discoveries to addressing hazards and threats.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Arbo, Peter, and Hersoug, Bjørn (2010). Oljevirksomhetens inntog i nord. Næringsutvikling, politikk og samfunn. Oslo: 56.

The environmental movement was expanding, and won support both from the left wing and from the centrist parties over fears of negative consequences for nature and the fisheries.

While green activism focused in the late 1960s and early 1970s on protecting nature and combating pollution, it developed during the 1970s into a political movement. Key roles were played here by eco-philosopher Arne Næss and Sigmund Kvaløy Setreng.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskDuring the first Offshore North Sea (ONS) exhibition and conference, held in Stavanger in 1974, an “alternative oil debate” was organised by the Rogaland Nature Conservation Society. This open meeting, under the title “Should oil revenues relieve world poverty or reinforce our own affluence problems”, attracted a capacity audience.

The new Future in Our Hands organisation led by Erik Dammann was responsible for the session together with Næss and Professor Torolf Rafto, best known as a human rights activist.

Farmer and fishermen organisations also backed it. They feared the “oil adventure” would not benefit their members, and played an active role as co-organisers and financial backers.

The alternative oil debate was also staged to coincide with ONS in 1976 and 1978. Activists from Friends of the Earth came from the USA to participate. But the effort to prevent oil drilling north of the 62nd parallel failed of its purpose.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thoring, Erik. (2014, 18 February) “Alternative oljetanker i oljebyen”. Friends of the Earth Norway.

During this period, both the environmental and fishermen’s organisations declared the waters above the 62nd parallel to be a protected zone.

Opposition among the fishermen had two drivers. One was the environmental threat, with potential harm to fish from oil spills. The other was considered even more dangerous: the menace to communities and established social structures.

Oil operations could cripple fishing across large sea areas and reduced opportunities for catches, thereby threatening the traditional local economic and social order.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskOpponents of drilling north of the 62nd parallel organised themselves in groups under the slogan “Oil or Fish?”. But they never managed to achieve broad mobilisation. Northern Norway could not let these threats be decisive. It needed the jobs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sejerstad, Francis (1999). Systemvalg og politikk. Universitetsforlaget: 62.

In White Paper no 81 (1974-75), presented in the spring of 1975, the Ministry of Industry said it expected to award production licences for a limited number of blocks as early as the autumn of 1976 or early 1977. Drilling could then begin in the summer of 1977 at the earliest.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 81 to the Storting (1974-75) Activities on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Reference was also made to a new White Paper which would be ready for the Storting’s spring session in 1976. The start to drilling was later postponed to 1978 because of the strict standards set for oil spill response.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting Proceedingss no 94, 10 March 1977. Petroleum exploration north of the 62nd parallel: 3028.

While the overall assessment was still based on technical and safety considerations, social and environmental consequences also acquired significance. Attention where the environment was concerned focused on the risk of oil blowouts, the level of oil spill response and possible damaging effects on fish and nature.

The first split between the political parties occurred in 1975-76, when the Labour government advocated a start to northern drilling in 1978.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 91 to the Storting (1975-76). Petroleum exploration north of the 62nd parallel.

White Paper no 91 (1976-76) emphasised that a moderate pace would have to be maintained in the opening phase, with special regard to “fisheries, safety and social adaptation”. The reason for the delay compared with the previous policy document was the need to build up a satisfactory system for oil spill response.

Admitting that the industry could never be made “completely risk-free”, the White Paper discussed the consequences of a possible blow-out but regarded its probability as very small.

The government concluded that “the degree of danger lies within a level of risk which can be accepted.” What should be regarded as “an acceptable level of risk” became the big question in the second half of the 1970s. But the Conservatives no longer wanted to fix a start date for drilling. After siding with Labour, the party was now seeking a coalition deal with the Christian Democrats and Liberals.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rommetvedt, Hilmar (2014). “Oljeleting nord for 62. breddegrad. Tilbakeblikk på en laaang beslutningsprosess”. Norsk Oljemuseums årbok: 47.

Following a lengthy debate on 10 March 1977, the Storting unanimously agreed that it “assumes a White Paper will be presented before a decision is taken to begin exploratory drilling for oil north of the 62nd parallel”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting Proceedings no 94, 10 March 1977 – Petroleum exploration north of the 62nd parallel: 3111-3112. The rapporteur was Arvid Johanson (Labour), chair of the industry committee.

The petroleum industry, the environment and drilling above the 62nd parallel also became topics for public debate, with the North Norwegian Petroleum Council was naturally in favour of drilling.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, logo, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, logo, engelskOn the other side, the Norwegian Fishermen’s Association wanted the northern NCS to remain closed for the near future. While not opposed to north Norwegian oil activity, it expressed clear doubts.

The association believed it would be possible to identify areas which were attractive to the oil explorers but not of interest – or at least less so – for fishing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy, vol 1, no 3, June 1975. Utålmodighet i nord.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskBusiness interests in northern Norway were becoming impatient. That found clear expression at an oil conference held in Harstad during February 1975, where north Norwegian industry was discussed from a regional policy aspect.

The main message from the conference was that the level of petroleum activity proposed by the government would be far too low. A “moderate” pace would be destructive for commercial life in the northernmost counties.

To have a regional policy effect, operations must be on a scale which could form the basis for a certain minimum level of activity. The northernmost counties needed jobs, it was noted, and sought badly needed specialist, technical and economic upgrades to their commercial foundation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy, vol 1, no 3, June 1975. Utålmodighet i nord.

Industry in northern and mid Norway felt it had spent years preparing for oil activities, but been faced with constant delays. Big sums had been spent without coming any closer to the goal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy, vol 1, no 2, March 1976. Vi må vite hvor vi står.

The biggest confrontations between fishing and oil interests occurred in mid-Norway, as reflected at a 1976 seminar held in Kristiansund by the Mid-Norway Petroleum Council and the Norwegian Petroleum Society.

Proposals from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) for drilling in two areas covering a couple of the region’s most important fishing grounds – the Langgrunn and Halten Banks – horrified participants.

These plans were completely at odds with the priorities of the petroleum council and the fishermen. The Fishermen’s Association stated that: “permitting any form of oil activity on the Halten Bank is out of the question”. Such conflicts of interest had not been seen in Norway’s oil debate earlier.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy, vol 2, no 9, November 1976. Forslag om boring midt i de viktigste fiskefeltene.

Fishermen fears were fuelled not so much by oil spills as by littering of the seabed with anchors, buoys, wire, iron girders, metal shavings and defective equipment left behind or dumped. All these items could damage fishing gear. A broader political split also emerged. Labour was not prepared to set a specific year, but wanted to speed up work on carefully mapping fishing interests.

The Conservatives were ready to allow exploration, but only after a research project had confirmed that possible pollution would not harm the fisheries.

And the farmer-oriented Centre Party would not be tied to a timetable. It supported a relatively early opening of the northern NCS, but only after the agricultural sector had been equipped to meet the oil age.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rommetvedt, Hilmar (2014). Oljeleting nord for 62. breddegrad. Tilbakeblikk på en laaang beslutningsprosess. Norsk Oljemuseums årbok: 52.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, Engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, EngelskHowever, the 1977 Ekofisk Bravo blowout in the North Sea made it difficult to approve oil exploration off northern Norway by the planned date of 1978.

This accident exposed with full clarity that Norway’s oil spill response was not acceptable. In the longer term, however, it helped to give ordinary Norwegians some reassurance.

The worst they feared had happened, but without visible lasting consequences. A horror scenario had been presented about the effects of a blowout, yet all traces of the big oil slick vanished after a spell of high seas.

Nevertheless, the accident revealed how badly prepared Norway was to deal with such incidents. Its oil spill response was subsequently geared up, with funds appropriated for research and new equipment.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, presse, nyheter, engelsk

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, presse, nyheter, engelskApproved at last

The Labour government under Odvar Nordli followed up the Storting’s 1977 request for a new policy document with White Paper no 57 (1978-79).

About half its 106 pages were devoted to safety, primarily the threat of oil spills from an uncontrolled blowout. It was clear that such incidents occurred fairly frequently during exploration drilling, but short-lived gas escapes were the most common. The probability of oil blowouts was low.

The relationship between the oil and fishing sectors occupied 11 pages of the White Paper, and a description of the drilling plans covered about 25. Yet again, the government concluded that an overall assessment showed limited petroleum activity in parts of the relevant areas to be acceptable.

The initial blocks in question were located on the Halten Bank and the Tromsø Patch further north, and the government proposed a start to exploration drilling in 1980.

Agreement had again been reached between Labour and the Conservatives when the industry committee produced recommendation no 293 to the full Storting in response to the White Paper. Regional policy effects and the need to learn more meant that drilling should be initiated as soon as practical, subject to the safety assumptions.

Views in the standing committee on industry were nevertheless divided over whether and when exploration should begin. The Christian Democrats, Centre Party, Socialist Left and Liberals, as well as Labour’s Lyder Nilssen and Georg Apenes from the Conservatives, voted for an alternative proposal to postpone drilling north of the 62nd parallel.

After a detailed review of safety, emergency preparedness and relations with fishing interests, the committee’s recommendation nevertheless concluded that exploration drilling for petroleum above the 62nd parallel could begin in the summer of 1980.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 293 (1978-79) from the standing committee on industry. Petroleum exploration north of the 62nd parallel (Report no 57 to the Storting).

This was finally approved by the full Storting against one vote on 25 May 1979.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting Proceedings no 238, 25 May 1979. Petroleum exploration north of the 62nd parallel.

Mexican blowout

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk, ixtoc, brønn, utblåsning

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk, ixtoc, brønn, utblåsningSoon after the Storting had sanctioned oil exploration in the Norwegian and Barents Seas, the unthinkable happened again. Mexico’s Ixtoc 1 well off Yucatán had a blowout on 3 June 1979.

More than 4 000 tonnes of oil per day flowed from the rig, which was not halted until October when the well was partly sealed. However, it continued to leak until a relief well had been completed in March 1980.

This ranked as the biggest marine oil pollution disaster at the time, and also raised questions about the performance of Norwegian oil spill clean-up equipment.

Thirty-five tonnes of this gear and almost a dozen experts were sent from Norway to the Gulf of Mexico, with Statoil in charge of the operation.

The state oil company announced at an early stage that the Norwegian clean-up equipment sent to Mexico functioned very well, with most of the oil spill collected on the first day by the 600-metre boom and two skimmers. It subsequently transpired that the gear had only been in use for 18 hours and that it mostly collected water.

But the blowout did not affect the allocation of blocks north of the 62nd parallel. Twenty-six were put on offer in the summer of 1979, six on the Halten Bank and 20 on the Tromsø Patch.

Yet another White Paper on petroleum activities above the 62nd parallel appeared in January 1980, and the Storting gave the final all-clear two months later.

The first three blocks were awarded on the same day. Statoil and Norsk Hydro received one each in the Troms I area, with Saga Petroleum becoming operator for one in Møre II. Exploration drilling on the northern NCS aroused strong passions. The conflict between developing industry and jobs on the one hand and concerns for a vulnerable north Norwegian coastal environment persisted.

The Ixtoc 1 blowout added fuel to the flames. Fishermen and nature conservationists were sceptical about drilling, and their protests found a variety of expressions.

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelsk

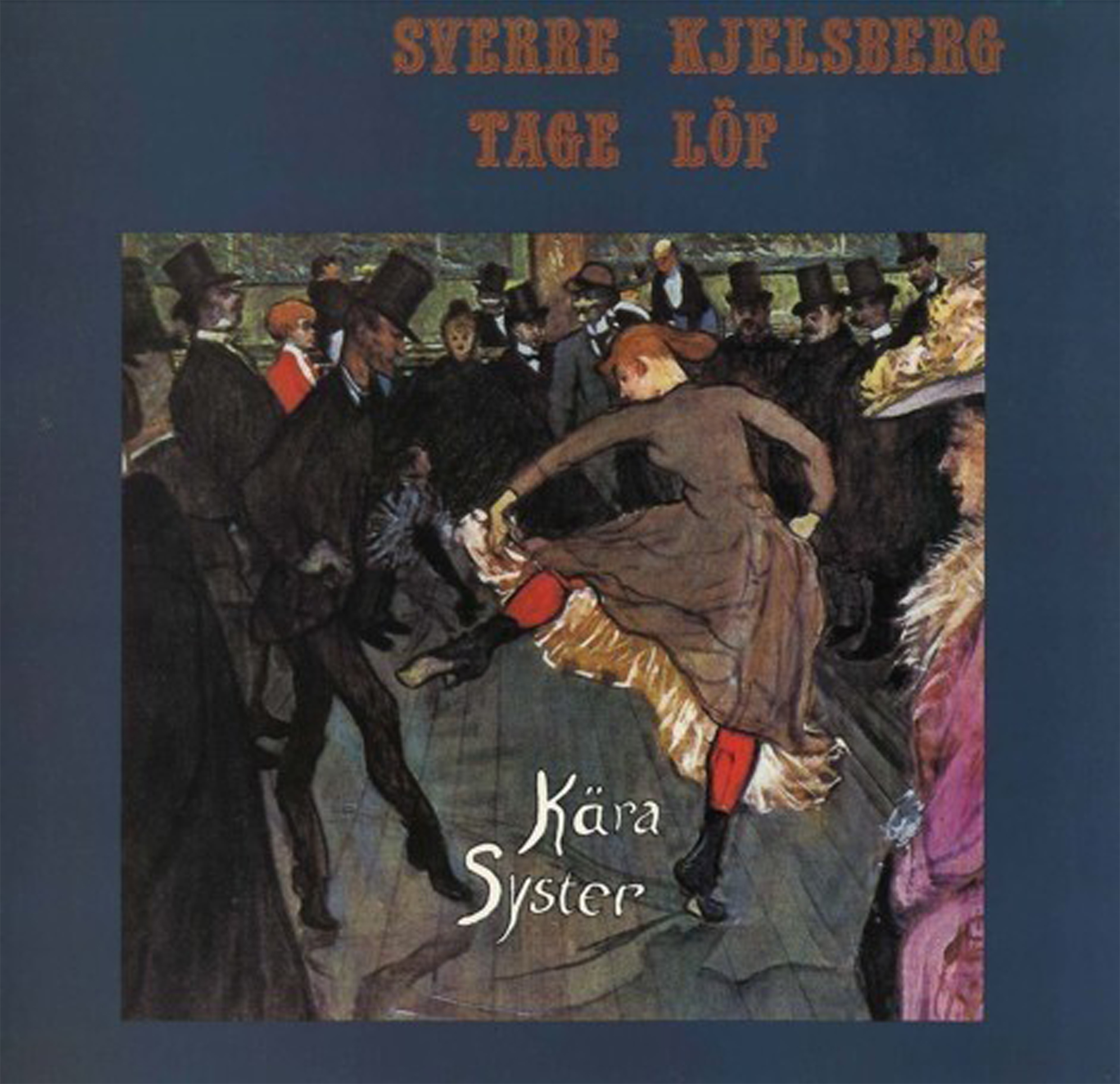

åpning av sokkelen i nord, 62, engelskThese included a song by well-known protest singer Sverre Kjelsberg, set to a bossa nova rhythm, which ended with a rejection of oil drilling. Its title was Acceptable level of risk.

Atlant-Oil established in KristiansundThe heliport at Kvernberget