Vestbase

Located at Vikan in Kristiansund’s Nordlandet district, the base is a wholly owned subsidiary of NorSea Group AS and ranked in 2017 as the main hub for offshore operations in the Norwegian Sea. Both the operator companies with permanent activity off mid-Norway (which includes Møre og Romsdal and Sør/Nord-Trøndelag counties) were then established at the base site.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Vestbase AS, downloaded on 11 January 2018 from its own website: https://www.vestbase.com/om-vestbase/vestbase-as (publication date unspecified).

Vestbase, engelsk,

Vestbase, engelsk,Alongside these two – A/S Norske Shell and Statoil ASA (now Equinor) – came some 60 supplier companies who were represented on the site. The Draugen, Heidrun, Åsgard B, Njord and Kristin platforms as well as the Åsgard A production ship were being supplied from Vestbase in 2017. And it also supported subsea developments Mikkel, Ormen Lange, Tyrihans, Yttergryta and Morvin. When the decision to locate the Draugen organisation in Kristiansund was taken in 1988, the Storting (parliament) gave emphasis to the presence of a functioning base. The Bill on this issue noted: “The company points out that experience shows a compact organisation with operations office, base functions and heliport in the same place has positive effects for [these] units.”

Vestbase was selected by the Storting as the supply base for both the Draugen and the Heidrun fields on the Halten Bank in the Norwegian Sea.

Long trek

Reaching this point had been a long trek. Efforts to turn Kristiansund into an oil base were driven by a small clique of forward-looking residents, who saw opportunities for the town as the “mid-Norway oil centre” from an early stage.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Those who want a more detailed description of the base issue in Kristiansund are recommended to read Hegerberg, H (2004). Et stille diplomati: Oljebyen Kristiansund 1970-2005. Kristiansund local authority. Large parts of this article are based on that work.

Local politicians started to work on this idea in 1970, which culminated at a meeting of the council’s executive board on 17 September 1970. The chief technical officer was asked to investigate and identify municipal and private properties able to provide quays which would be suitable for servicing oil exploration.

This “base decision” showed that Kristiansund wanted a special role if offshore operations were extended above the 62nd parallel (the northern limit of the North Sea). Read more in the article on opening this part of the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). It is worth observing that this meeting took place less than a year after Norway’s first commercial oil discovery – Ekofisk, about as far south on the NCS as it could get – and nine months before that field came on stream.

Kristiansund’s new identify as a petroleum centre is so closely linked to this date that the town now celebrates 17 September as Oil Day every year. While the town’s oil committee took the initiative on this development, good collaboration between the council and local industry helped to lay the foundations for Vestbase.

When the facility could finally open a decade later, both these parties had invested large sums every year and devoted considerable work to turn it into a reality. Attractive sites were reserved from an early stage so that they would be available for establishing possible industrial activity at a later stage. While the chief technical officer identified potential sites, others made a big commitment in preparing and drawing up unified strategies and forging contacts with relevant players.

The local authority was well prepared and united when opportunities to attract petroleum-related operations arose. And the whole Nordmøre district also spoke with one voice here.

On 9 October 1972, council chairs from the region collectively identified Kristiansund as the natural base location for petroleum exploration off Møre og Romsdal. This was followed up by the county’s oil committee in the following February. Even more positively, the oil committees in both Sør- and Nord-Trøndelag called in March 1973 for the base to be in Kristiansund. This regional unity would prove important.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solberg, J. (2009). Det Norske Oljeeventyret: En Analyse Av Den Petroleumsrelaterte Utviklingen I Midt- Og Nord-Norge.

To see how a small town in mid-Norway succeeded in winning the fight on this important issue of base location for the region, and later for Draugen, the process must be considered step by step. It took a decade, and many obstacles had to be overcome.

Committee

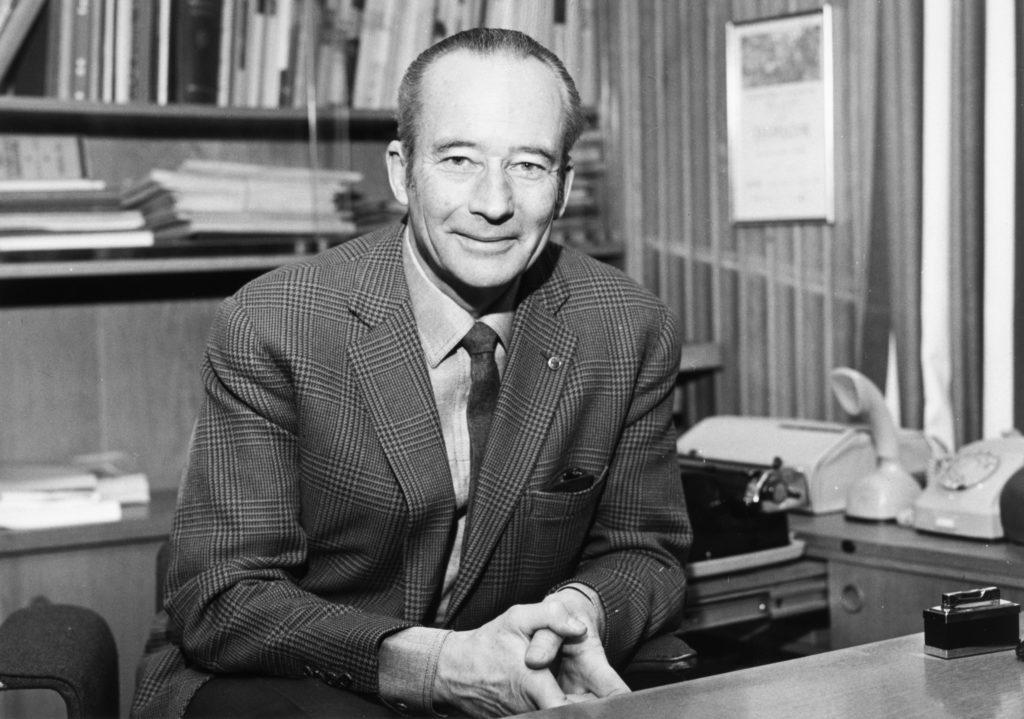

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk,Kristiansund’s oil committee was formed in 1970 to secure a supply and service base for the town, and included mayor Asbjørn Jordahl from Labour until he was elected to the Storting in 1977. Other founder members were consul and shipbroker William Dall from the Conservatives (until 1980), and pharmacist and Liberal Otto Dyb (until 1995, chair from 1980).

In addition came chief technical officer Ole Gunnesdal (until his death in 1979) and council architect Kristian Sylthe (until 1991, when he left the local authority). During its early days, the committee received good advice from central government through confidential contacts with Oluf Christian “Ossi” Müller. Born in Kristiansund, the latter was now secretary general at the Ministry of Industry and friends with key members of the oil committee – particularly Dall, who he had been to school with.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hegerberg, H. (2004). Et stille diplomati: Oljebyen Kristiansund 1970-2005. Kristiansund: Kristiansund kommune.

Müller also urged the town and committee to prepare sites for possible petrochemical industry. This called for much larger areas – 200-300 hectares and preferably port facilities for big tankers.

vestbase, engelsk,

vestbase, engelsk,Kristiansund was a small local authority in 1970, covering just 22 square kilometres – making it Norway’s smallest incorporated town – spread over several islands. So it was not easy to find suitable land within the municipal boundaries. The only option for attracting large-scale industry to the region was to ally with neighbouring local authorities. A collaboration established with Averøy, Frei and Tusna functioned well, and yielded a joint document in 1972 where areas potentially suited for various industries were presented.

This work proceeded in parallel with identifying appropriate sites for a supply base. The oil committee believed in any event that such a facility should lie within Kristiansund’s boundaries. All possible and less-than-possible locations were mapped for a possible future exploration base. They had to be at least 0.8 hectares, able to provide a quay and lie within the town limits.

The first list from the committee included eight candidates, mostly in the town centre, with the former gasworks site in the urban core as the first choice.

A more detailed analysis admittedly showed that all eight were on the small side and offered little opportunity for expansion because they were hemmed in by existing buildings.

So the search continued, and new areas were mapped. Three additional sites were introduced in January 1971 – including the one at Vikan. An important document in this identification work was the general plan for area utilisation in Kristiansund, which the council had been working on since 1968 and published in 1971.

This divided the town’s restricted acreage into five “development guidelines”, with three defined as areas where employment activities would be concentrated. Nordlandet, the largest of the town’s islands, already had established industry and the largest amount of unutilised land suitable for industrial operations and jobs.

According to the plan, further commercial activity was to expand where it already from before. But a secondary centre for services and manufacturing would be created in Nordlandet’s Løkkemyra-Vikan area. So Vikan was in the loop as early as 1971.

The oil committee’s results were published in an advertising brochure for distribution to central government agencies and interested companies.

This aimed to acquaint Norway’s emerging petroleum sector with what Kristiansund had to offer for a future supply base when offshore operations moved north. Jordahl penned a covering letter.

An overview of potential base sites within the town limits was presented in the brochure. Although it was small, with limited expansion opportunities, the gasworks site – now a town-centre car park – found a place on the list.

So did Holmakaia, right behind the town hall, and naturally also Vikan. The latter area lay on the southern shores of Nordlandet.

Others get involved

The town council and its oil committee were not alone in preparing for a new era and a new industry. Kristiansund’s two big shipyards – Sterkoder and Storvik Mekaniske Verksted (SMV) – lay on the north side of Nordlandet and wanted their share of the oil cake.

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelsk

Kristiansunds tidligere historie, engelskSterkoder and its CEO, Arnfinn Kamsvåg, mobilised early and tackled the issue on two fronts – becoming an offshore fabricator and establishing a service base.

For this purpose, the company secured a new site at Smevågen in Averøy, Kristiansund’s neighbouring local authority to the south-west. This island is linked to the town today by the Atlantic Tunnel, which opened in 2009. In the 1970s, however, communication between the two communities was still by sea.

Where a base was concerned, Sterkoder established a dialogue with Norsco – one of the three big companies operating bases in and around Stavanger. The idea was ultimately to combine the offshore workshop with a supply facility. But Kristiansund council and the oil committee were unenthusiastic about a base in Averøy.

For its part, SMV contacted North Sea Exploration Service, another of Stavanger’s base companies, and worked actively to get control of neighbouring properties at Dale in Nordlandet to build a supply base alongside its own yard. West Coast Service was established in the autumn of 1971 by SMV, with 40 per cent, North Sea Exploration Service, with 40 per cent, and Kristiansund Finans with the remaining 20 per cent.

This company represented a precautionary move in order to be ready when oil exploration eventually began above the 62nd parallel. It remained dormant, with a modest share capital. The oil committee was happy to see these signs of competition, at a time when no timetable had been set for extending offshore operations to the continental shelf off Møre og Romsdal. No White Papers had yet addressed this issue, and everything remained very uncertain. See the article on opening the northern NCS.

Hopeful

In order to realise its petroleum dream, Kristiansund had to get central government on its side. The town was very hopeful that the Storting would designate it as mid-Norway’s main supply base. The Ministry of Local Government appointed a joint local authority committee in 1972 to assess location requirements and choices for future bases above the 62nd parallel.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ministry of Industry (1976). Petroleumsundersøkelser nord for 62°N, Report no 91 (1975-76) to the Storting, Oslo: 52. Downloaded from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1975-76&paid=3&wid=g&psid=DIVL807.

Appointed at the initiative of Kristiansund native Müller, among others, this body established a number of general criteria for determining which town would be chosen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hegerberg, H. (2004). Et stille diplomati: Oljebyen Kristiansund 1970-2005. Kristiansund: Kristiansund kommune: 48 These include a central position in relation to the opened areas – in other words, those parts of the NCS where the government would permit future oil and gas exploration.

The chosen town also had to be close to an airport which met a high standard and provided the capacity to accommodate heavily laden aircraft. That was supplemented by a need for good communications by sea and land, where port conditions included quays and cranage for heavy lifts, and where land was available in reasonable proximity. Access was also necessary to well-equipped workshops and other industrial services, and the urban community should offer versatile service and environmental provision. The final – and perhaps most important – requirement was that the location for mid-Norway’s oil service base had to meet both oil and not least regional policy goals.

This list might have been written explicitly with Kristiansund in mind. Its airport had opened in 1970 and access to the sea was straightforward. Land links were more of the problem. The town was spread over three islands which were closely tied to each other, but would lack a road connection with the mainland until 1992.

The committee’s report, submitted on 27 October 1972, recommended Kristiansund as the site of a main service base for petroleum exploration off mid-Norway.

Regional policy considerations weighed heavily. A base “would be of great significance in strengthening the economic basis of the region,” the report noted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ministry of Industry (1974) Virksomheten på den norske kontinentalsokkelen m.v, Report no 30 (1973-74) to the Storting. Oslo: 56. Downloaded from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1973-74&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL920.

Kristiansund was in decline at the time, with industry contracting and unemployment high. At the same time, it was centrally located for offshore exploration off mid-Norway. Representatives from the town visited the industry ministry in December 1972, two months after the committee had presented its recommendation.

As we have seen, the town was a strong base candidate because it met most of the requirements set by the government. But this was not enough for the ministry – Kristiansund had to obtain collective support from the whole region.

Support

The town took this challenge seriously. It contacted the other local authorities in Møre as well as the county governors of More og Romsdal and Sør/Nord-Trøndelag to draw up a joint plan for a regional petroleum policy. Møre og Romsdal’s county oil committee was the first to express its support on 6 February 1973 after voting five to one for Kristiansund as the main supply base. The dissenting voice came from Ålesund, the principal town in Sunnmøre further south, which was pursuing its own ambitions at the time to secure an offshore base.

Support from the region was one thing, but Kristiansund’s own council had yet to take a decision. This occurred on 7 February 1973, with a unanimous vote to support the base proposal. The resolution also stated that partners would be sought and that the council would begin talks with Østlandske Lloyd, part of the Fred Olsen shipping group, on building a base at Vikan.

With the signing of a letter of intent between these two parties, the council had indicated that it intended to allocate the area around Vikan for a future oil base.

Regional declarations of support continued to arrive. On 19 February, the Møre og Romsdal county executive board backed Kristiansund by 10 votes to one – Ålesund again in opposition.

The executive boards for Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag county councils followed with unanimous votes on 9 and 21 March respectively. Support from these mid-Norway councils increased the likelihood that the Storting would approve Kristiansund as an oil centre, and allow the dream to become reality.

No legislation existed in the early 1970s which specified that the Storting was to decide when and where petroleum bases could be built round the country. In principle, both local authority and private base companies could set up shop wherever they fancied. But some opportunities for official control nevertheless existed.

Being selected by the Storting did confer some advantages, such as access to basic investment through the Regional Development Fund and to favourable government loans. However, this was changed in 1973 when the ultimate decision on the positioning of main supply bases was assigned to the Storting.

To ensure greater powers over the location and number of major oil-related projects, the government introduced a temporary Act to regulate the establishment of companies.

That made the petroleum sector subject to more detailed regulation than any other industry in Norway, primarily to achieve efficient control of new and expanded operations in areas experiencing development pressure. This in turn allowed the authorities to keep total activities within the confines of overall national resources and to achieve a reasonable regional distribution of such operations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lunde, H and the Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Labour (1974). Etableringskontroll og lokaliseringsveiledning, Norwegian Official Reports (NOU): 46. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

In regional policy terms, the Establishment Act was viewed as important for spreading more of the oil industry to economically underdeveloped areas.

The Act specified in part that “no development of bases for the petroleum industry … may be initiated before the King has given his consent.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ministry of Finance (1974). Petroleumsvirksomhetens plass i det norske samfunn, Report Nr 25 (1973-74) to the Storting: 80. Downloaded from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1973-74&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL658. Applications for such projects were to be sent to the local government ministry and submitted to relevant county governors and county/local councils. In other words, the central government would decide – in consultation with both counties and local authorities – who could be allowed to call themselves a “base town”.

The temporary legislation was replaced by a permanent Act on 20 February 1976. It lost much of its significance from the late 1980s and was repealed in 1994. After the boost provided by support from the rest of mid-Norway, the remainder of 1973 proved a time of waiting for Kristiansund council and its oil committee.

Everyone was waiting for clarification from the Storting on the location issue and for a decision to start oil exploration off mid-Norway.

The final settlement of the first question was provided on 15 February 1974, when White Paper no 25 on the place of petroleum in Norwegian society was issued by the finance ministry.

Known as the “oil report”, this recommended that “the area off Trøndelag and Møre will provide the basis for establishing a base in Kristiansund”. This decision aroused no controversy in the Storting, and was ratified unanimously. The mood in Kristiansund was naturally jubilant. But the celebrations were somewhat muted by the government’s simultaneous pronouncement that exploration above the 62nd parallel would start off northern Norway, and then move south. Admittedly, the White Paper said a rapid opening of areas outside the Møre/Trøndelag coast would be desirable. But it looked as if it might take many years for the first rig to show up there.

As long as the government refrained from allowing exploration drilling, no base would be needed. That depended on operations out to sea. The Storting’s standing committee on industry also supported the choice of Kristiansund as the main base location. Finally, the town had secured the acceptance it had been pursuing for so many years. But much work remained before the base became a reality.

White Paper no 25 was followed up by the industry ministry’s own White Paper no 30 on offshore activities, where specific proposals for the start to exploration were presented.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ministry of Industry (1974). Virksomheten på den norske kontinentalsokkelen m.v. Report no 30 (1973-74) to the Storting. Oslo. Downloaded from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1973-74&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL920. Drilling would begin off Troms in the far north during 1975 or 1976, and outside Møre and Trøndelag at roughly the same time or a little later.

With only two years until activity could get going off their own coast and with the Storting’s blessing as a base town, the Kristiansund council could finally initiate construction. However, two key questions remained to be answered – where would the base be located, and which company was to build and operate it.

Decision time

As noted above, the town council had voted in February 1973 that the area around Vikan was to be used for a base and signed a letter of intent with Østlandske Lloyd. Nevertheless, the oil committee was also working with West Coast Service at Dale in collaboration with SMV and wanted two areas to be put into operational condition. While Vikan was admittedly intended to be the main supply base in the long run, it was possible that a smaller facility at Dale would be needed in the first exploration phase.

In January 1975, the Kristiansund council made a formal approach to Statoil to establish collaboration over a service and supply base. The state oil company was positive. But wanted it to wait for the government and would not commit until the Storting decided when oil activities would begin off mid-Norway and how extensive they would be. This was due to be specified in a promised White Paper, and construction of a base could not begin until that document had been produced.

In early 1976, the council started work on an application to the Ministry of Local Government for a licence to set up a base pursuant to the 1973 Establishment Act, and for state funding. Just when everything appeared to falling into place, new obstacles arose. In particular, a decision on oil drilling in the north turned out to be taking much longer than expected.

This delay prompted Østlandske Lloyd to withdraw from the Vikan project on 26 September 1975, two years after it signed the letter of intent with the council.

The company was dissatisfied with the government’s policy on private-sector involvement in oil operations, while it also had financial problems because of a shipbuilding recession.

So what was the oil committee to do now? Its new plan aimed to put together a group comprising Statoil and other oil companies, local enterprises and the council to build and operate the base jointly. This facility was conceived as a combination of business park and base. To make the best possible provision, the council now acquired 180 000 square metres in Vikan for the project.

A budget for investment in and operation of the planned base area was presented in December 1975, and a construction project finally looked like getting off the ground. The first draft of a timetable was ready in January 1976. But Sterkoder had not given up. It also approached Statoil over a supply base on Averøy, offering the state company 50 per cent while it took 25 per cent and Kværner the remainder.

But the latter was not a natural partner for Statoil, and this proposal failed to win acceptance. Sterkoder and Kværner continued the work as a joint venture. This proved an eye-opener for Kristiansund. The town now had to decide if it was not to lose what had been sought for so long on the last lap.

The council and oil committee feared that exploration drilling would begin off mid-Norway before the Vikan facility was ready, and had to find an interim solution.

They turned yet again to SMV in order to lease quays and base areas until Vikan was operational. The yard was positive, and keen to negotiate a lease. In White Paper no 91 (1975-1976) on petroleum operations above the 62nd parallel, which finally appeared in April 1976, the ministry said it wanted only one base company in Kristiansund.

Involving local industry as much as possible in petroleum-related service operations was another of the conditions set. The council was expected to back companies which wanted to establish service functions on a base.

At the same time, the council was encouraged by the ministry to invite Statoil to collaborate on such a facility. The White Paper noted that the town’s oil committee was already in discussion on this issue with North Sea-West Coast Service and Atlantoil, as well as the state oil company. The most interesting section of the White Paper for Kristiansund detailed when drilling was to start. It finally announced that oil exploration off Møre and Trøndelag would begin at the same time as further north in 1978.

Statoil was to bear the main responsibility for such drilling and would be able to demand a 50 per cent interest, or more, in all production licences.

Too small

A preliminary design was now produced for the Vikan base, but this process made it clear that the 16-hectare site was too small. It needed to be at least 20 hectares.

In addition, it would be expensive to develop, the topography was irregular, the quays were difficult to access and had poor seabed conditions, and weather conditions were generally unstable. A bit late in the day to discover all this now.

Neither the oil committee nor the rest of the local authority could see any alternative within the town limits, and the committee found itself wavering.

It and the council had no other option but to look again at the costs of the Vikan site compared with Sterkoder and SMV. After some discussion, a lease of the Dale site was sought.

New delays

An oil blowout occurred in a well on the Ekofisk field on 22 April 1977. The offshore accident which everyone had feared was now a reality. Nobody was killed, but the 2/4 Bravo platform sprayed out oil for almost seven days. This incident sparked new debate on whether and when to open the NCS above the 62nd parallel for exploration.

On this occasion, however, the delay was welcomed by Kristiansund. After six years of work, no base existed yet and no company had been formed to run it. The oil committee, which had worked so hard and been so positive, was down for the count. But the autumn of 1977 marked a turning point for the town as a base. Fresh forces made their appearance – not least in the shape of Thor Sætherø, the council’s new chief financial officer.

He was a man with initiative and liked to operate on his own. After contacting both the ministry and Statoil, he agreed with the latter to launch preparations for establishing a base company. Under the agreement, this locally based enterprise would be a partner with Statoil but the latter would own at least 50 per cent. Kristiansund council and regional industry both had to participate.

The approach adopted in building up a base company utilised the model developed by Statoil for the support facility at Harstad further to the north.

Company formed

Midt-Norsk Baseservice AS was formed in December 1978 as a local enterprise which would “work for the shareholders’ participation in and benefit from the activity which oil exploration and the possible subsequent production phase would generate”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hegerberg, H. (2004). Et stille diplomati: Oljebyen Kristiansund 1970-2005. Kristiansund: Kristiansund kommune: 114

The company was to provide the oil industry with information about what its shareholders could offer in the shape of goods and services, and forge contracts between them and oil companies. It would also organise inspection tours, study trips and conferences, and help to establish new enterprises which would be needed when oil operations got going. Another aim was to become a shareholder in the base company due to be set up.

In March 1979, a base site for the exploration phase had still to be chosen. Statoil aimed to have a facility ready for operation in Kristiansund on 1 April 1980. The oil company took the view that preparation of the Vikan site was now urgent, and should start not later than 1 July 1979. After nine years, time was suddenly short.

A formal decision to establish the Vestbase facility at Vikan was not taken by the council until 30 March 1979. Construction started on 30 July and the base was inaugurated on 27 May 1980.

Kristiansund council installed power, water and so forth, while Statoil – which leased the land – took responsibility for and funded development of the necessary base facilities.

In parallel, the final green light for exploration above the 62nd parallel was given by the Storting in May 1979. The deadline to apply for licences in these waters was set as 1 August 1979, with drilling to begin in May 1980.

Operational

The main job of Vestbase was to offer space and equipment at all times for supporting petroleum activities off mid-Norway. Facilities included personnel, outdoor storage and quays.

In addition came bulk warehousing with heated and refrigerated stores, offices, stockpiles of oil spill clean-up gear, transport equipment and containers. The base also offered a range of goods and services such as ship’s chandlery, technical maritime requisites, shipping agents, container services, steel rope and chain, and customs clearance.

It was initially owned 40 per cent by Midt-Norsk Baseservice A/S with 40 per cent, Statoil 40 per cent and Saga Petroleum 10 per cent. Vestbase functioned well from the start, but did not have that much to do. A total of 15.5 work-years were performed during the first year. Strangely enough, however, local industry stayed away. More companies eventually moved in. Activity at the facility fluctuated in line with operations off mid-Norway but did not really take off until Draugen came on stream in 1993.

Norske Shell was awarded exploration acreage outside the Møre and Trøndelag coast in 1984, and established an operations office at the base. By 27 July that year, Shell knew it had found oil and Draugen was declared commercial on 14 May 1987. That marked the start of the fight for the operations organisation and supply base.

Covering 600 000 square metres of harbour area, Vestbase is now the main supply base for petroleum operations in the Norwegian Sea. In 1990, it secured the transport assignment for the Draugen development – characterised as “the biggest contract so far in mid-Norway”.

This job was important not only because of its size, but also because it brought the base new expertise which would be very important for the future. The contract was secured at a favourable moment for Vestbase, and saved it during a difficult time. The company was split in 1994 into an operations arm (Vestbase AS) and a property enterprise (Vikan Eiendom AS). As the base has developed, other property companies have been established, including Vikan Næringspark Invest AS.

Vestbase AS is now wholly owned by NorSea Group AS, a leading national player for port and base operation.

Other important milestones for the facility include:

- 1995 Heidrun, platform, operator: Statoil ASA

- 1997 Njord, platform, operator: Statoil ASA

- 1999 Åsgard A, production ship, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2000 Åsgard B, platform, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2003 Mikkel, subsea development, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2005 Kristin, platform, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2007 Ormen Lange, subsea development, operator: A/S Norske Shell

- 2009 Yttergryta, subsea development, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2009 Tyrihans, subsea development, operator: Statoil ASA

- 2010 Morvin, subsea development, operator: Statoil ASA

The facility has developed from being a purely logistical hub into an operation and service centre for offshore-related operations. It is now a business park rather than simply a base, hosting more than 60 companies with 700-800 employees.

Its own organisation has about 210 staff, making it Kristiansund’s biggest private employer.

Operations during the first 20 years after 1980 related mainly to base and supply functions. But Vestbase has seen a sharp growth since 2010 in technical and other petroleum-related services, with more expertise-based jobs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergem, B. (2013). Ringvirkningsanalyse av petroleumsklyngen i Kristiansundsregionen: Status 2012 og utsikter frem mot 2020 (Vol. 1306, Rapport (Møreforsking Molde: trykt utg.)). Molde: Møreforsking Molde.