Petoro – a state-owned partner

The state’s direct financial interest (SDFI) covers shares in production licences, fields, pipelines and land-based plants associated with the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).

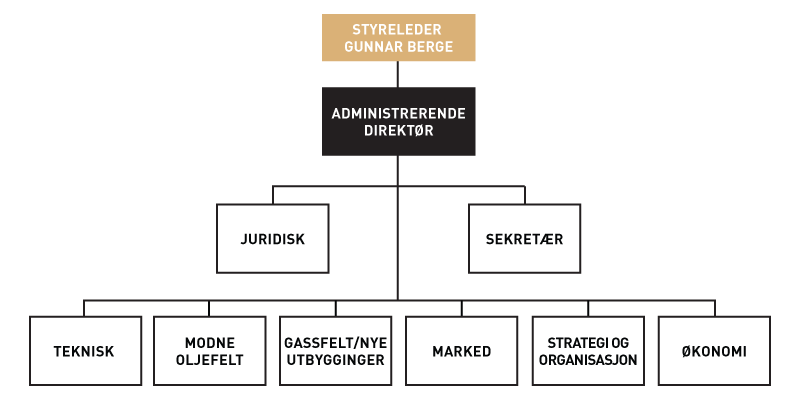

petoro en statlig partner, illustrasjon, engelsk

petoro en statlig partner, illustrasjon, engelskThis makes the government a participant in its own right in the oil industry, and the assets involved include a third of Norway’s petroleum reserves. Although precluded from acting as an operator, Petoro otherwise works like any other oil company where the aim is to maximise revenues for its owner – in this case the state. But it differs from other players in that it is only a manager, not the actual licensee on the NCS. It administers the SDFI holdings which belong to the state.

Petoro therefore receives no revenues from the SDFI, nor does it contribute to any investment. All income and costs generated by the state’s interests are channelled over the government budget.

As the actual licensee, the government must meet its share of investment and costs while receiving a comparable share of revenues from each asset.

Petoro’s own operating costs are met by annual appropriations from the government. Nor does it sell the petroleum produced. This is done by Equinor (ex Statoil) together with its own output.

The Petoro name combines petra, meaning stone, or petroleum, which means “rock oil” and oro, meaning gold.

Creation

Petoro was founded on 9 May 2001, but the company’s history actually goes back in many ways to the original creation of the SDFI in 1985. Discussion raged in the early 1980s about state oil company Statoil’s rapid growth to a dominant position in Norway’s petroleum industry and the Norwegian economy in general. The non-socialist coalition led by Kåre Willoch was concerned about this relatively young enterprise being responsible for such as large part of the government’s revenues.

A broad compromise negotiated between the Willoch government and the Labour Party included transferring about 50 per cent of Statoil’s licence holdings to what became known as the SDFI.

The state had previously had interests in production licences, but through Statoil. These were now split into an SDFI share and one retained by the company.

That meant the state became the direct holder of shares in oil and gas fields, pipelines and land-based plants. The percentage size of these holdings varied from asset to asset.

Subsequently, the SDFI has been given its own share in new offshore licences awarded by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The main purpose of this change was to separate the cash flows which would otherwise have gone to Statoil, and channel one part of them directly to the Treasury. To achieve this, the state had to become a direct licensee on the NCS with a corresponding responsibility for investment and operating costs, and exposure to risk.

The civil service was not geared to running commercial activities on the scale required by the SDFI. Statoil was accordingly asked to administer these interests.

That system persisted until the oil company was partially privatised in 2001. During this period, the SDFI was pretty anonymous. Both partners and the public saw only Statoil.

The management system involved the state company selling the SDFI’s oil and gas together with its own – a solution which has continued after Petoro was established.

In connection with Statoil’s stock market listing in 2001, the responsibility for running the SDFI portfolio was transferred to Petoro. But the Storting (parliament) imposed restrictions on the latter’s operations. As noted above, it is not allowed to be an operator. Its workforce was also restricted to 60 people – the new company was not intended to grow into another Statoil.

The latter merged in 2007 with the oil and energy division of Norsk Hydro, and the ceiling on Petoro’s staffing was lifted. It would now need to do more technical and commercial work itself.

petoro en statlig partner, logo, engelsk,

petoro en statlig partner, logo, engelsk,Licensee

Pursuant to the regulations, one of Petoro’s duties as a licensee both on Draugen and elsewhere is to ensure that the operator runs a field in a prudent and efficient manner. That applies not least to such areas as health, safety and the environment (HSE), where Petoro – like all licensees – is required to promote continued progress on the NCS.

petoro en statlig partner, logo, , engelsk,

petoro en statlig partner, logo, , engelsk,The Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA), responsible for supervising HSE in Norway’s oil sector, conducted audits of Petoro as a licensee in 2002 and 2015.

Covering the company’s whole involvement on the NCS, the 2002 check left the regulator with a “positive impression”. Petoro had a functioning HSE management system, it found. In addition, the PSA established that the company discharged its duty of seeing to it that the operator acted properly, and had an active and conscious attitude to its role as licensee.

petoro en statlig partner, engelsk,

petoro en statlig partner, engelsk,The 2015 audit looked on Petoro’s role in the Draugen licence and also covered Norske Shell as the operator. No nonconformities or improvement points were found on this occasion either. “Our general impression … was that management at both Norske Shell and Petoro covering the subjects of the audit are satisfactory, and no breaches of the regulations were found,” the PSA report states. “Nor were any improvement points identified.”

It appears that Petoro does its job as partner and manager of the SDFI well. That is important when the company ranked in 2018 as by far the largest company on the NCS in terms of oil and gas output. Through Petoro, the state has direct interests in 203 production licences, 39 producing fields and 16 partnerships for pipelines and land-based plants. Net cash flow from the SDFI in 2018 is estimated at NOK 77.4 billion.