Completing and installing

Mating and tow-out.

To start with, the platform ranked at the time as the tallest structure ever towed. It was also the first fixed installation to be positioned above the 62nd parallel – making the tow-out the longest to date on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, plattformen plasseres på feltet, forsidebilde

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, plattformen plasseres på feltet, forsidebildeThe Condeep monotower was readied in March 1993 to receive the topsides, which were to be towed from Stavanger to the deepwater mating site at Vats.

On 24 March, the concrete structure underwent a trial submersion which left only a few metres of the shaft visible above the sea surface.

This operation was a nervous time, with the Sleipner sinking (see separate article) the year before still fresh in the minds of most people present. But everything went as planned.

plattformen plasseres på feltet, engelsk,

plattformen plasseres på feltet, engelsk,In the meantime, the topsides were being completed at Stavanger’s Rosenberg Verft yard. On 6 March, this structure was transferred to two huge barges and towed to Vats by five tugs.

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, engelsk, plattformen plasseres på feltet,

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, engelsk, plattformen plasseres på feltet,Mating was accomplished by manoeuvring the barges into position over the concrete shaft and deballasting the gravity base structure (GBS).

Tolerances were narrow. The maximum permitted deviation from an ideal match of topsides and shaft was a mere 40 millimetres – so accuracy was essential in all stages of the operation.

As large volumes of water were pumped from its storage cells, the GBS rose, took over the weight from the barges and continued to raise the topsides high above the sea surface.

The mating operation was completed entirely to plan, and all that remained before the platform could begin its journey north was to hook up piping and cable systems.

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, plattformen plasseres på feltet, utslep, engelsk,

bygging av betongdelen til plattformen, plattformen plasseres på feltet, utslep, engelsk,In beautiful weather, the tow-out began on 3 May. Six big tugs with a combined 75 000 horsepower in bollard pull were needed to cover the 830 kilometres to the field.

As mentioned above, this was the longest-ever tow for a Condeep platform. Completing the voyage without risk depended more than ever on a long period of fine weather.

The operation took 10 days at an average speed on 1.5 knots. It crossed the 62nd parallel – the northern boundary of the North Sea – at 04.58 on 11 May, and reached its destination on 13 May.

The platform was finally in position on 17 May, Norway’s Constitution Day, and an improvised parade was staged on the helideck.

Installation on the field

rov-arbeid inni draugen, forsidebilde, slep, engelsk,

rov-arbeid inni draugen, forsidebilde, slep, engelsk,Some concern was expressed when the tow began in early May because an error in casting the GBS had created a problem for ballasting the platform down on the field.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Eivind Wolff, Norwegian Contractors project director, 20 October 2016.

Extensive seabed surveys and geotechnical sampling had been conducted on Draugen as early as 1992. These revealed that the platform site comprised very soft clay over a harder layer.

As a result, the platform was equipped with nine-metre long skirts to ensure good penetration. However, their thick walls would displace much of the unconsolidated seabed material.

plattformen plasseres på feltet, engelsk,

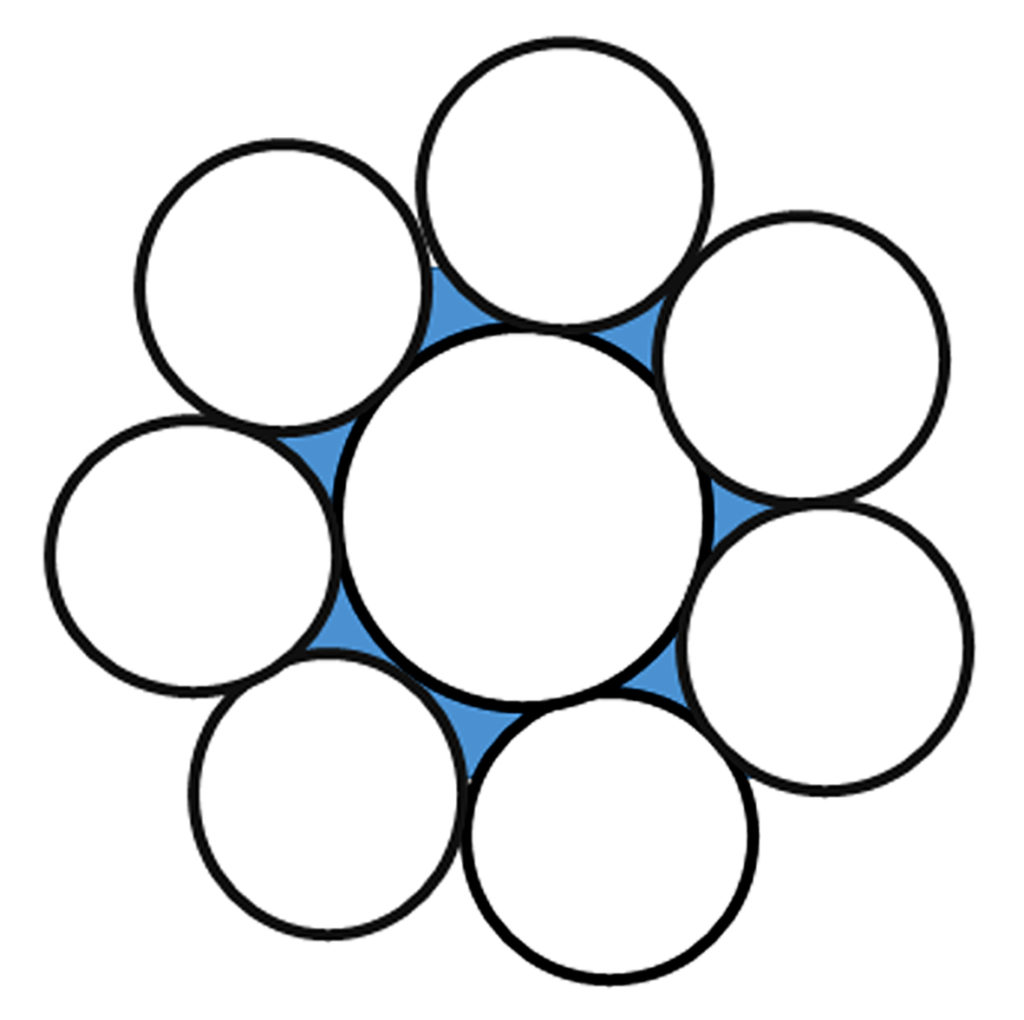

plattformen plasseres på feltet, engelsk,This soft clay would be squeezed into all the spaces beneath the storage cells, including the three-cornered gaps formed when three cylinders are placed next to each other (see figure 1).

Unfortunately, an inspection had revealed that these supposed three-cornered spaces were not empty but had been filled with concrete.

This meant the seabed material had nowhere to go when the skirts penetrated. That could cause a soil collapse, damaging the whole platform foundation and perhaps leaving it unusable.

The casting error and poorer bottom conditions than expected meant that the tolerance for positioning the GBS had to be narrowed from a diameter of 20 metres to just eight metres.

Sigbjørn Egeland, Shell’s construction supervisor for the GBS, sums up what happened as follows:

When the platform had bee placed just two metres from the ‘bull’s eye’, the job of ballasting down began to ensure adequate skirt penetration in the seabed. This would normally have been a relatively straightforward process – simply pumping water out of the storage cells so that external water pressure would drive the structure into the seabed. The skirts had almost reached full penetration when we were informed that only half of them were in contact with the hard layer. The soft clay overburden was thicker than expected and the hard layer sloped slightly. This sparked an extensive and hectic series of meetings to find a solution to the unexpected discovery. To achieve a solid ‘landing’ and ensure a good grip on the hard clay by the remaining parts of the skirts, the platform had to be positioned ‘slightly askew’.[REMOVE]Fotnote: E-mail from Sigbjørn Egeland, Shell’s construction supervisor for the concrete GBS, 14 February 2017.

This proved very challenging. The solution adopted was to adjust the internal underpressure in the cells. But that created pressure differentials on different sides of the platform.

The was process very extensive and difficult. Nobody had done anything like it in practice before, and calculating the amount of pressure differential was complicated.

Things had to done calmly and carefully, and took at least a week longer than a normal installation. The result was that the platform had a tilt of about 0.3 degrees (“I think the exact figure was 0.296 degrees,” says Egeland).

That might not seem like much, but on a structure more than 300 metres tall it adds up to a horizontal offset of about 1.5 metres. The lifts and the derrick had to be adjusted accordingly.

Those who complained most were the pool players – all the balls accumulated in one corner.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Bjarne Jensen, Shell’s survey representative for installation of the Draugen platform, 11 October 2016.

The big moveStarting production