The Draugen Reservoir

reservoaret, illustrasjon, engelsk,

reservoaret, illustrasjon, engelsk,The field was discovered by the very first wildcat. This initial exploration well was plugged and abandoned six months after the award of the production licence.

Running in a north/north-westerly direction, Draugen is about 21 kilometres long and six wide. Its reservoir lies about 1 600 metres beneath the surface and is typically 40-50 metres thick.

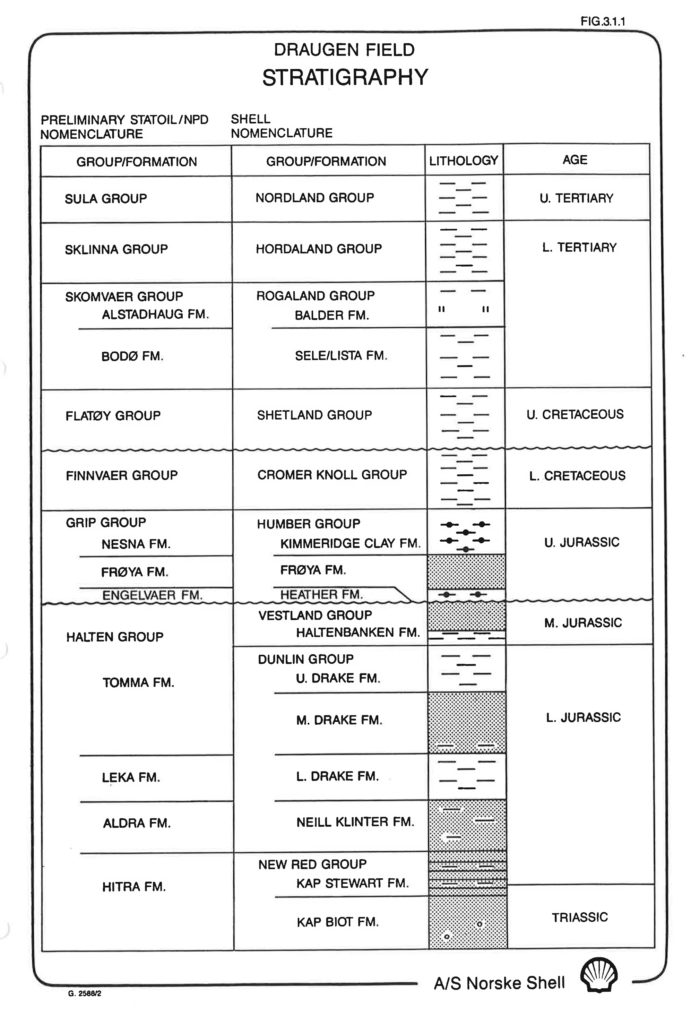

Oil is found in the Rogn and Garn formations, which date from the Late and Middle Jurassic.[REMOVE]Fotnote: A/S Norske Shell (September 1987) Plan for development and operation (PDO). Six wells were drilled to determine field size and extent before the plan for development and operation (PDO) was submitted.

At an early stage in maturing Draugen, ahead of the PDO, stock tank oil initially in place (Stoiip) was put at 1.1 billion barrels with an estimated recovery factor of 30-40 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Note dated 14 July 1986 from J van der Burgh, Shell EP.

Geology

Before an oil field can be brought on stream, it has a long history. First of all, the geologists must determine that three basic requirements are present.

- Deposition of permeable and porous sandstone where oil can accumulate – reservoir rock.

- Sediments where oil can form initially – source rock.

- An impermeable layer lying over the reservoir which prevents the oil from leaking out – cap rock.

On Draugen, the Rogn formation provides the main sandstone reservoir while the cap and source rocks are the same – the Spekk claystone formation.

The Rogn interval was laid down on top of Spekk clay around 150 million years ago, during the Late Jurassic period. Europe and America/Greenland were still close to each other then, and the water depth ranged from a few metres to 20 metres – very different from today’s 250 metres.

At that time, dinosaurs and other reptiles were the only big animals in the area which was to become Draugen. No fossils of these creatures have been found, but some cores have shown signs of trees.

The oil lies in the pores between sand grains ranging in size from crystals of table salt to small peas. Most are similar to the eggs in cod roe (rogn in Norwegian – hence the formation’s name).

reservoaret, illustrasjon, engelsk,

reservoaret, illustrasjon, engelsk,As the sea level rose, further Spekk clays were deposited over the sand and eventually formed a carpet impenetrable to liquids and with a high content of organic materials.

These derived from the remains of microscopic plankton (algae), which render the Spekk shale dark. The clay is even a little radioactive.

Under the right conditions, the organic deposits also give rise to oil. Before this crude can escape from the shale, it has to be warmed up a good deal.

Burial of the Spekk formation under 2-3 000 metres of rock or more meant that the temperature generated from the Earth’s natural heat became high enough to cook out the oil.

However, the area where Draugen lies today has never been buried more than about 1 600 metres beneath the seabed. That was never deep enough for crude to form.

But the rocks lay much deeper to the west of the field, and this is presumably where the Draugen crude comes from. It has migrated under the Spekk cap rock to the points nearest to the surface.

This process is driven by the force of gravity – oil floats on water, and rises until it meets an impermeable barrier.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Knipsheer, Jan Hein (1994). Geologien på Draugenfeltet, EPOinfo no 3: 11. The neighbouring Njord and Heidrun fields derive from the same source.