The Condeep story

om å jobbe på glid, parkering, jåttåvågen,

om å jobbe på glid, parkering, jåttåvågen,The formation of Norwegian Contractors (NC) in 1973 as a joint venture between A/S Høyer-Ellefsen, Ingeniør F Selmer A/S and Ingeniør Thor Furuholmen A/S nevertheless demonstrated that the country had its own resources for meeting the big new challenges.

This became particularly clear through a unique creation – the concrete deepwater structure (Condeep) to support production facilities on the continental shelf.

These gravity base structures (GBSs), which sit solidly on the seabed through their own weight, introduced prestressed concrete as a construction material for the offshore sector.

They combined a number of technical advantages with a short construction time and low lifetime costs, and thereby represented big savings for the oil companies.

Norwegian Contractors

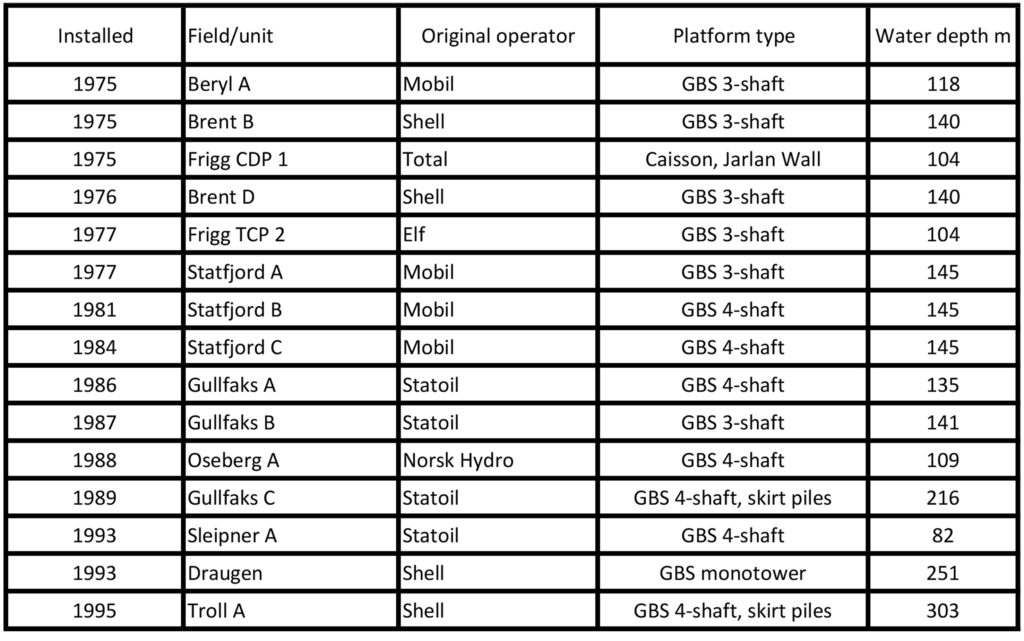

NC’s development can be split into three phases, starting in 1973 with the contract to build the first Condeep for Mobil’s Beryl A platform in the UK North Sea sector.

The initial five years were a typical pioneering period, where attention was concentrated on delivery and less concern was paid to further development.

This period ended with the delivery of the GBSs for Statfjord A and the TCP-2 platform to stand on the Frigg field in the course of 1977.

The next phase covered 1978-88 and embraced the construction of six Condeeps – all for licences operated by Norwegian companies.

It was now the government demanded that it must be possible to remove concrete platforms from the fields when production had ceased. All Condeeps had to be designed accordingly from 1980.

The final phase began in 1988 with the start to constructing the first Sleipner A GBS and ended with the delivery of the Troll A platform in 1995.

NC made a big leap forward technologically during this period by introducing several new platform solutions simultaneously, both fixed and floating.

Water depths down to 300 metres represented a particular challenge, and the Draugen GBS marked an important product in this context.

The Sleipner A GBS sank in the Gands Fjord in April 1991 (see separate article). This had consequences for the whole of NC and posed challenges for the Draugen, Troll and Heidrun platforms.

Condeep

Many people contributed to the development of the Condeep concept. Three who were particularly important in this context are mentioned here.

Engineer Olav Mo came up with the idea for the structure, and played a big role in its technical refinement. He later applied for a patent covering the design.

Helge Molland was the executive responsible for developing collaboration with other companies and for the active market cultivation required to succeed with such a pioneering project.

His enthusiasm and ability to put the case allowed him to make a big contribution in the demanding initial period.

Dr techn Olav Olsen was Norway’s leading expert on shell structures and involved in the development work from the word go. He produced the final solution used for Beryl A and played a highly significant part in subsequent designs.

Olsen won international recognition with the award of the Gustave Magnel gold medal for the Draugen platform design in 1991.

Construction

Many people earned their first oil money and financed their studies through long summer days on and beside the Gands Fjord, where these concrete gravity base structures (GBSs) were raised by a process known as slipforming. Stout backs and strong arms were required to build these huge structures. One experience is described below.

Some of these workers have also regarded their experience of the platforms and constructing them as the great challenge of their lives.

One of these was Swede Gunnar Gramnes, who wanted to give the Norwegian oil adventure a try during the summer of 1986 and has provided the following account (abridged).

“There were 1 200 of us. We came from Cameroon, Angola, Czechoslovakia, Canada, Poland, West Germany and the UK, and naturally from Finland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

“We included experienced old construction workers, who got the jobs they wanted, young people who had fled unemployment at home, university students and a few expectant adventure-seekers.

“There were almost as many different reasons for being there as there were souls. But we all shared two motives – to make money and to participate in the world’s biggest slipforming operation to date.

“I was personally one of the adventure-seekers. That’s how it felt, at least, when I boarded the train at Stockholm’s central station for the 17-hour journey to Stavanger.

om å jobbe på glid, jåttåvågen, engelsk

om å jobbe på glid, jåttåvågen, engelsk“Pouring concrete was my job, and God knows I did enough of it. The old office-worker body suffered a real shock after its first shift – eight hours of continuously pushing a wheelbarrow with 150 kilograms of concrete.

“This went on round and round a scaffold inside cell E4. When the chance came for a break after four hours of intensive work, I ached everywhere and was convinced that the adventure would end after a single shift.

“The mood in cell E4 was high-spirited throughout that summer. I was lucky, and worked only with Norwegians. And I’ll never forget my eight cell comrades.

“A great camaraderie developed between us as we struggled with or against the ever-rising formwork, which climbed remorselessly at its fixed rate of 53 centimetres per shift.

“I managed to complete my 12 regular shifts, and even an extra one, and returned home from Stavanger considerably stronger and with greater self-confidence than ever.

“Whenever I tell curious colleagues about my days on the ‘slip’, I feel a sense of pride – over surviving the big strength test, over the good camaraderie, over learning about other working lives remote from my own.

om å jobbe på glid, parkering, jåttåvågen, engelsk

om å jobbe på glid, parkering, jåttåvågen, engelsk“And I’m proud of having been involved with the fantastic structure which an oil platform represents.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, &., & Norwegian Contractors. (1993). På dypt vann : Norwegian Contractors 1973-1993. Oslo: [Norwegian Contractors].

Working on the slip has also inspired poetry of the kind written by Erling Thu and included in his 1976 collection of Condeep Kvardagsdikt (Everyday Condeep Verses). See the Norwegian version of this article for an example.